Fig. 5.1

Normal arterial anatomy of the upper limb

After crossing the inter-epicondyle line, the brachial artery trifurcates in the upper fourth of the forearm into the radial (usually the more dominant branch), ulnar, and interosseous (also called “median”) arteries. The radial artery gives off two terminal branches at the wrist, near the anatomical snuffbox. These then anastomose with terminal branches from the ulnar artery to form the superficial and deep palmar arches which may have several anatomical variants. The deep arch takes a straight and short convex course inferiorly, while the superficial arch is more tortuous and ends approximatively 1–2 cm below the base of the metacarpals (Fig. 5.2). The anatomy of the digital arteries which arise from the convexity of the arcades is also subject to variability. Each digit is supplied by the medial and lateral digital arteries, both terminating in the distal pulp space.

Fig. 5.2

Arteriogram showing the superficial and deep palmar arches

Anatomical variability is a common feature of upper limb vasculature. Vascular radiologists, despite years of experience, sometimes encounter difficulties in deciphering normal from aberrant anatomy during fistulography. The subclavian artery rarely presents with variant anatomy except for an aberrant right subclavian artery that arises from the aortic arch beyond the origin of the left subclavian artery. It then crosses the midline posterior to the esophagus to supply the right upper limb.

Variant anatomy more commonly involves the brachial artery, particularly at the elbow. The most common is a high origin of the radial artery (15–20 % of cases). The radial artery may originate at any level from the axillary artery to the elbow (Fig. 5.3). Thereafter, the other arterial segment is no longer the brachial artery but the ulnar–interosseous trunk, which ultimately gives off the ulnar and interosseous branches below the elbow. An interesting phenomenon frequently associated with a high radial artery origin is the formation of an anastomotic arcade between it and the ulnar–interosseous trunk in the upper third of the forearm (Fig. 5.4). The caliber of this anastomotic arcade is usually smaller than that of the radial artery but can increase in size if there is a stenosis on the proximal radial artery (Figs. 5.5 and 5.6).

Fig. 5.3

The most common arterial anatomical variant: a high origin of radial artery. The diagram also shows a less common high bifurcation of the radial artery in the forearm

Fig. 5.4

Illustration showing the sometimes-present supernumerary anastomotic arcade at the elbow between the radial artery and the ulnar–interosseous trunk

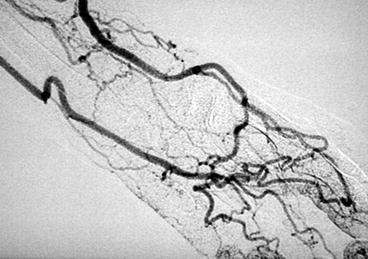

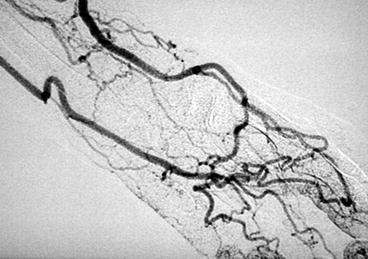

Fig. 5.5

The radial artery may be atrophied or occluded above the elbow. Its forearm segment may only be supplied by the supernumerary anastomotic arcade

Fig. 5.6

(a) This arterial phase of a low flow radial–cephalic fistula shows what appears to be a strange, tortuous origin of the radial artery. This is in fact the anastomotic arcade from the ulnar–interosseous trunk which opacifies the upper arm portion of the radial artery before the brachial portion seen on (b). (b) This upper arm run shows the high origin of the radial artery. (c) This later phase shows opacification of the upper arm segment of the high-origin radial artery. This delay is caused by a radial artery stenosis or spasm at the elbow. There is also a distal peri-anastomotic radial artery stenosis that will be dilated via a retrograde venous approach

The ulnar artery can, to a lesser extent, have a high origin and then accompanies the main radial–interosseous trunk down the upper arm (Fig. 5.7). An interosseous artery with a high origin is extremely rare.

Fig. 5.7

High origin of the ulnar artery

The terminal branches of the radial artery may bifurcate in the mid-forearm, several centimeters above the wrist, such that an AVF arising from it is fed by one of the terminal branches instead of the main trunk (Figs. 5.3 and 5.8). Numerous collaterals can also form between the radial, interosseous, and ulnar arteries in the forearm as a result of proximal radial artery stenosis (Fig. 5.9a, b).

Fig. 5.8

This arteriogram of a radial–cephalic fistula shows that the anastomosis was created with one of its two terminal branches rather than the radial artery itself

Fig. 5.9

(a and b) These two phases of the same arteriogram with forearm prone show a high radial–cephalic fistula with a severe peri-anastomotic stenosis. Numerous collaterals run from the ulnar and interosseous arteries to the distal radial artery whose retrograde filling compensates the proximal stenosis

Fig. 5.10

Normal non-variant venous anatomy, rarely seen in practice in the forearm

At the wrist and hand, complete palmar arches are more the exception than the rule. The arches are more commonly asymmetric and incomplete with hypotrophic or stenotic segments. The digital arteries are not always aligned and symmetrical and may give off tiny collaterals particularly in recurrently traumatized areas.

5.2 Venous Anatomy

There are two types of veins in the upper extremity: superficial veins found immediately beneath the skin and deep veins which accompany the arteries and constitute the venæ comitantes of those vessels. Only superficial veins are suitable for AVF creation in the forearm.

Despite having more anatomical variation than arteries, the cephalic and basilic veins are predominantly seen veins in the forearm and upper arm of normal subjects.

The main cephalic vein drains from a venous network on the dorsal aspect of the hand at the posterolateral border of the wrist. It winds posteroanteriorly and then lateromedially toward the elbow where it joins the median basilic (cubital) vein medially and the median cephalic vein laterally which ascends as the upper arm cephalic vein.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree