Interventional Radiology in Liver Transplantation

Introduction

Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) has become a well-established technique since the first reported human transplant performed in 1963, with survival rates of over 80% at 1 year in both adults and children.1, 2 OLT is now the treatment of choice for irreversible liver cell failure and selected cases of hepatocellu-lar carcinoma (HCC). Nonetheless it remains a technically challenging procedure and its success is highly dependent upon the correct selection of patients before transplantation and the accurate diagnosis and treatment of complications after the transplantation procedure. Radiology plays an essential role in both of these areas.

The commonest liver transplantation procedure is whole-organ OLT. The shortage of available donor organs has led to innovative techniques of reduced-size “split” and living related donor liver transplantation, which were driven largely by the need to provide donor livers for pediatric recipients; However, living related transplantation is now being used in the adult population as well.

The role of interventional radiology (IR) in pre-OLT assessment has decreased as noninvasive imaging modalities have improved, but the introduction of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure has had a notable impact in selected patients awaiting OLT. The role of IR in the assessment and treatment of post-OLT complications remains vital. In its simplest form, successful OLT requires effective anastomosis of the donor and recipient inferior vena cava (IVC), portal vein, hepatic artery, and bile duct, and the correct level of immunosuppression to prevent rejection but avoid infection or malignancy.

Interventional Radiology Before Transplantation

The aims of pre-OLT imaging are to evaluate technical feasibility by determining hepatic vascular anatomy, and to determine the suitability of OLT in cases of HCC by assessing the presence and extent of hepatic malignancy. Whilst noninvasive imaging with ultrasound, multiphase contrast-enhanced spiral computed tomography (SCT), and gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the mainstays of this evaluation, IR techniques are still of use in specific instances.

Hepatic Artery

A detailed knowledge of hepatic arterial anatomy is not required for OLT, and extrahepatic arterial anatomy is readily appreciated on noninvasive imaging. Detailed segmental hepatic arterial anatomy is, however, required in the setting of living related OLT in order to plan the segmental splitting of the donor liver and avoid devascularization of individual segments. Formal angiography currently has superior resolution to both SCT and MR angiography and is indicated in this setting. Ultrasonography is inaccurate for assessing hepatic arterial anatomy.

Portal Vein

An adequate portal vein inflow is essential to graft survival. Portal vein thrombosis is present to some degree in 5-10 % of patients with end-stage cirrhosis, notably those with HCC. Portal vein thrombosis does not necessarily preclude OLT, but it may necessitate modification of surgical technique. Patency of the portal vein is usually demonstrable on noninvasive imaging, but occasionally angiographic delineation is required to confirm the exact extent of portal vein thrombosis and anatomy of venous collaterals. The portal vein thrombosis is usually demonstrated by means of indirect hepatic arterioportography, unless there is hepatofugal flow, in which case it can be demonstrated by wedged hepatic venography using either iodinated contrast medium or carbon dioxide.

Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt

TIPS has become an important pre-OLT interventional technique in selected patients. It is very effective at reducing portal hypertension and is used to “buy time” for end-stage cirrhotic patients suffering the complications of portal hypertension, notably variceal hemorrhage and ascites, and is described in both the adult3–6 and pediatric7 populations. Although TIPS can, rarely, precipitate a rapid decline in liver function necessitating emergency transplantation, in most patients there is an improvement in liver and renal function, allowing optimization of the patient’s condition prior to transplantation. In this situation TIPS acts as a “bridge to transplantation.”

Comparison of OLT in patients with and without TIPS show no difference in terms of perioperative transfusion requirements, operative time, length of hospital stay, and outcome. Therefore, TIPS is not indicated simply to reduce portal venous pressure prior to transplantation.3–6

Although these studies show that TIPS has no direct bearing on the outcome of surgery, they do report modification of surgical technique being required in 22-35% of patients.3,6 In most cases this is due to migration or misplacement of the stent. If the upper end of the stent extends too far proximally into the IVC or right atrium or the lower end too far into the portal vein, it can interfere with cross-clamping at surgery, making it difficult to control these vessels and perform the necessary anastomoses. Fortunately, transplantation surgeons have developed various techniques for dealing with poorly positioned stents8 so these rarely jeopardize the procedure. Nevertheless, extreme care should be taken when deploying the TIPS stent in patients who are candidates for OLT.

It is worth noting that comparisons of OLT in patients who have previously undergone surgical portosystemic shunting to patients with TIPS9,10 do show a higher mean operative time and similar or increased blood-product transfusion requirements and duration of hospital stay in the surgical group. No difference in long-term survival was seen; nonetheless TIPS remains the preferred method of portal decompression prior to OLT.

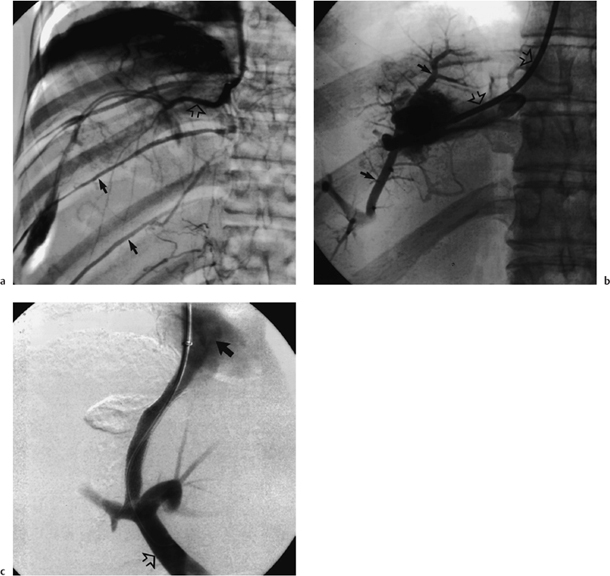

A particularly interestingly indication for TIPS as a “bridge to transplantation” is Budd-Chiari syndrome.11,12 Although technically challenging in this syndrome because of the variable degree of obliteration of the hepatic veins, TIPS has been successfully performed in both acute and chronic cases (Fig. 12.1). Occasionally TIPS allows recovery of liver function to such a degree that transplantation is no longer required.

TIPS has also been used to treat portal vein thrombosis prior to OLT,13 thereby eliminating the need for surgical thrombectomy or bypass grafts.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Long-term success following OLT for HCC depends mainly upon avoiding recurrent disease. The risk of recurrent disease is related to the size and number of tumors, the presence of vascular invasion, and the presence of extrahepatic spread. Stages I and II of HCC have five-year survival rates of 60-75%, compared to only 15-20% for stages III and IV of the disease.14

The presence and extent of HCC is usually determined with noninvasive imaging, but IR retains a role as a problem-solving tool in equivocal cases and in the temporary control of HCC in patients awaiting OLT.

Lipiodol Angiography

Lipiodol is known to be retained by HCC. An emulsion of Lipiodol and iodinated contrast medium is injected selectively into the hepatic artery and unenhanced CT performed 10-14 days later. Dense focal retention of Lipiodol is highly suggestive of HCC, with a positive predictive value of 90%,15 and therefore may help in characterizing indeterminate focal lesions. This technique, however, has low sensitivity in screening for occult foci of HCC before OLT.16

Temporary Control of Disease

Having diagnosed HCC amenable to OLT, there is frequently a wait of weeks or even months for a suitable donor organ to become available. The question then arises as to whether treatment should be instituted to delay tumor growth but which could jeopardize the success of future OLT. As HCC is resistant to systemic chemotherapy and radiotherapy, targeted local treatments are required. These fall into two groups: (1) transarterial and (2) percutaneous.

Transarterial Therapy

Targeted chemotherapy or radiotherapy using chemotherapeutic agents or iodine-131 emulsified with Lipiodol can be delivered to the tumor by selective catheterization of its feeding hepatic artery. The effect of these agents can be enhanced by additional embolization of the feeding artery with either Gelfoam or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles. There is some evidence that Lipiodol-iodine-131 therapy following resection of HCC reduces tumor recurrence and increases disease-free survival,17 but such adjuvant treatment has not been assessed in patients undergoing transplantation for HCC.

Percutaneous Therapy

Numerous techniques for percutaneous ablation of HCC now exist. Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) and radio frequency thermal ablation are most commonly used for HCC, but percutaneous acetic acid injection, interstitial laser hyperthermia, microwave coagulation, and cryotherapy are also described. Percutaneous and transarterial techniques may be combined. No controlled trials of pre-OLT use of these techniques exist, but PEI has been reported to produce survival rates comparable to those for HCC resection.18 A potential concern with these procedures is the risk of percutaneous seeding of tumor, reported at 2.3% for PEI,19 which could compromise long-term survival after OLT. It is worth noting that percutaneous needle biopsy of HCC is associated with a needle-tract implantation rate of 3.4-5.1 %21 and should therefore be avoided in potential OLT candidates.

Summary point:

Summary point:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree