(1)

Princess Elizabeth Hospital Le Vauquiedor St. Martin’s Guernsey, Channel Islands, UK

(2)

Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Brighton, England UK

Abstract

Screening mammography has been successful in detecting small and early cancers, resulting in favourable prognoses. At the same time, this has also resulted in detection of previously occult benign breast disease. The distinction between benign and malignant lesions is not always simple. Although some mammographically detected lesions such as calcifying fibroadenomas, oil cysts, intramammary lymph nodes, vascular calcification and lipomas have pathognomonic features, a relatively large group of soft tissue lesions or calcifications are mammographically indeterminate. In these cases, the diagnosis can be confirmed only by needle core biopsy or surgical excision.

With co-author Louise M. Gaunt

Learning Points

A few benign lesions such as oil cysts, calcified fibroadenomas and vascular calcification have diagnostic mammographic features.

Most mammographic calcification in benign lesions is indeterminate.

Ultrasound is the best investigation to differentiate cysts from solid lesions.

MRI is better for assessing lesions in dense breasts than other methods.

Directional vacuum-assisted core biopsies can remove small benign calcified lesions.

3.1 Background to Benign Breast Lesions

Screening mammography has been successful in detecting small and early cancers, resulting in favourable prognoses. At the same time, this has also resulted in detection of previously occult benign breast disease. The distinction between benign and malignant lesions is not always simple. Although some mammographically detected lesions such as calcifying fibroadenomas, oil cysts, intramammary lymph nodes, vascular calcification and lipomas have pathognomonic features, a relatively large group of soft tissue lesions or calcifications are mammographically indeterminate. In these cases, the diagnosis can be confirmed only by needle core biopsy or surgical excision.

Most publications on benign breast disease are based on symptomatic lesions, and the true incidence in the screening age group is unknown. However, the prevalence of benign disease ranges from 6 % to 27 % in the screening age group (Burnett et al. 1995; White et al. 2001). Because of the increase in longevity, most screening programmes now invite women in the 50–70 age group for mammographic screening. Some institutes screen women up to the age of 75 (Chinyama et al. 2003; Ernst et al. 2002; Jonsson et al. 2003). UK NHS screening programme extended the screening age group to 70 in 2006. Screening older women invariably increases the number of mammographically indeterminate lesions. If a conclusive diagnosis cannot be attained by nonoperative techniques such as fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) or needle core biopsy, this will prompt an excisional biopsy. Screening older women will have an impact on the workloads in breast disease units.

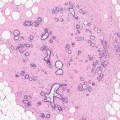

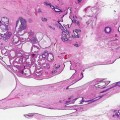

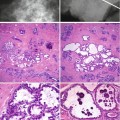

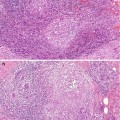

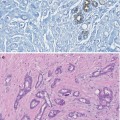

Detection of breast disease by imaging techniques depends on soft tissue abnormalities and calcification, which can occur in isolation or in combination. Architectural abnormalities exhibit different shapes and sizes, which also result in variable imaging density. Benign breast lesions produce a heterogeneous array of soft tissue densities caused predominantly by an increase in fibrosis or a mixture of fibrosis, elastosis and epithelial proliferations. Soft tissue mammographic abnormalities include coarse fibrosis, ill-defined fibrosis, single or multiple nodular densities, generalised increase in density or stellate structures such as radial scars.

Several studies have reported an increased risk of breast cancer in women with increased soft tissue density on mammography (see Chap. 16). However, assessment of mammographic density is associated with inter- and intraobserver variation. Jackson and co-workers (1991) studied the radiographic densities in 91 biopsy-proven (51 benign, 40 malignant), nonfatty, non-calcified breast masses. the kappa statistics interobserver agreement was low (0.22–0.49), with an overall sensitivity of 48 %, specificity of 80 % and both negative and positive predictive values of 66 %. The authors concluded that in isolation, mammographic density was of limited value in predicting the nature of non-calcified benign or malignant lesions. Although it is accepted that mammographic density is high in young women, assessment of breast tissue in postmenopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy can also be difficult because of an increase in density or water retention.

Calcification occurs both in benign and malignant lesions. Mammographic calcification plays an important part in detecting early in situ cancer. The microcalcification noted mammographically is usually much larger than that identified microscopically. For this reason small microcalcifications are often detected in lobules in histological sections in the absence of mammographic calcification. Calcification related to individual lesions is described in detail in the specific chapters.

3.2 Mammography

Mammography is the main radiological modality used in breast screening and applies similar principles to ordinary X-ray. However, to obtain meaningful results, adequate breast compression should be performed. Although for patient management purposes, breast disease is classified into symptomatic and screen-detected, in most breast units, symptomatic patients are also assessed mammographically or by ultrasound to increase diagnostic accuracy. The main mammographic features of benign breast disease are parenchymal abnormalities caused by increase in soft tissue density or calcification, which can occur independently or in combination. Mammography is more sensitive and specific in assessing fatty breasts than dense breasts. Dense breast tissue is particularly difficult to assess in young women (see above). A definite benign diagnosis is possible mammographically with lesions such as oil cysts, calcified fibroadenomas, lipomas, intramammary lymph nodes and possibly hamartomas. Mammography is also used in assisting needle core biopsies and for localisation of impalpable lesions.

The American College of Radiology (1998) devised a reporting system, the BI-RADS lexicon (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System), which is intended to produce uniformity in mammographic reports. The lexicon is reproduced with permission of the American College of Radiology (ACR).

3.2.1 BI-RADS Assessment Categories

3.2.1.1 Assessment Is Incomplete

Category 0

Need Additional Imaging Evaluation: Finding for which additional imaging evaluation is needed. This is almost always used in a screening situation and should rarely be used after a full imaging workup. A recommendation for additional imaging evaluation includes the use of spot compression, magnification, special mammographic views and ultrasound. The radiologist should use judgement in how vigorously to pursue previous studies.

3.2.1.2 Assessment Is Complete: Final Categories

Category 1

Negative: There is nothing to comment on. The breasts are symmetrical, and no masses, architectural disturbances or suspicious calcifications are present.

Category 2

Benign Finding: This is also a negative mammogram, but the interpreter may wish to describe a finding. Involuting, calcified fibroadenomas, multiple secretory calcifications and fat-containing lesions such as oil cysts, lipomas, galactocoeles, and mixed density hamartomas all have characteristic appearances and may be labelled with confidence. The interpreter might wish to describe intramammary lymph nodes, implants, etc. while still concluding that there is no mammographic evidence of malignancy.

Category 3

Probably Benign Finding– Short-Interval Follow-Up Suggested: A finding placed in this category should have a very high probability of being benign. It is not expected to change over the follow-up interval, but the radiologist would prefer to establish its stability. Data are becoming available that shed light on the efficacy of short-interval follow-up. At the present time, most approaches are intuitive. These will likely undergo future modification as more data accrue as to the validity of an approach, the interval required and the type of findings that should be followed.

Category 4

Suspicious Abnormality–Biopsy Should Be Considered: These are lesions that do not have the characteristic morphologies of breast cancer but have a definite probability of being malignant. The radiologist has sufficient concern to urge a biopsy. If possible, the relevant probabilities should be cited so that the patient and her physician can make the decision on the ultimate course of action.

Category 5

Highly Suggestive of Malignancy–Appropriate Action Should Be Taken: These lesions have a high probability of being cancer.

3.2.2 Advantages of Category Reporting

The advantage of the lexicon is that there are precise definitions of lesions that are probably benign and this allows the woman with a category 3 lesion to choose either surveillance mammography or biopsy. Caplan et al. (1999) analysed the data from the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program and found that 7.7 % of the 372,760 mammograms were classified in the BI-RADS category 3. This category was more likely to be reported in young women who were symptomatic and had abnormal clinical examination. Reporting of category 3 also varied among radiologists from different regions or states and ranged from 1.4 % to 14 %. In a separate study, Lacquement et al. (1999) reported a high percentage of women with category 3 mammographic reports who were referred for image-guided biopsies. The authors reviewed 688 image-guided biopsies: category 3 lesions represented 46.8 % of the biopsies, followed by category 4 with 34 % of the biopsies and category 5 with 15.4 %. The authors concluded that the BI-RADS did not improve the quality of the risk assessment information by making the positive predictive value more specific to a patient’s mammogram. The findings were in contrast to those previously reported by Liberman and colleagues (1998). Of the 492 mammographically detected, impalpable lesions that were referred for surgical excision, only 8 (2 %) were reported as category 3, 355 (72 %) as category 4 and 129 (26 %) as category 5.

Since the publication of the first edition, the BI-RADS system has further been developed. Repeat mammography should be complete within 6 months as there is a 2 % risk of breast cancer in this category (ACR 2003). The classification also includes category 6 which are lesions identified on imaging with cancer proven on biopsy and the patient is awaiting definitive treatment (Eberl et al. 2006). The BI-RADS system is also applicable to ultrasound and MRI (ACR website).

The UK National Health Service Breast Screening Programme (NHSBSP) applies a similar reporting system, which was adopted by the European Society of Mastology with the following reporting categories: R denotes radiology (Perry 2001).

R1 = Normal/benign breast tissue

R2 = A lesion with benign characteristics

R3 = An abnormality with indeterminate significance

R4 = Features suspicious of malignancy

R5 = Malignant features

According to the NHSBSP, women with R1 and R2 mammographic reports require routine follow-up according to local screening guidelines (every 2–3 years). Women with R3 mammographic reports require biopsy, and the decision for short-term follow-up should be considered at a multidisciplinary meeting and agreed with the woman. The NHSBSP standard requires that fewer than 1 % of screened women should be placed on short-term recall. Short-term recall should not be used as an alternative for proper assessment, which could be viewed as failure in decision-making (NHSBSP 2001). Needle core biopsy is mandatory for R4 and R5 lesions.

Sickles (1995) recommends that the BI-RADS category 3, probably benign, should be restricted to impalpable lesions and interpretation should be performed in conjunction with previous mammograms to exclude a progressive lesion. In a separate study, Brenner and Sickles (1997) compared the cost of surveillance mammography and stereotactic core biopsies of probably benign lesions. They compared 3,184 women who underwent surveillance mammography with 161 patients who underwent needle core biopsies. The cost of managing probably benign breast lesions with surveillance mammography was US$ 3,307,575 less than if all the lesions had been managed by needle core biopsies. The cost ratio of needle core biopsies to surveillance mammography was 8:1. The authors concluded that, with similar false-negative rates, needle core biopsies were more costly than surveillance and this has a negative effect on the management of probably benign breast lesions, unless the lesion had altered during surveillance, which should prompt a diagnostic biopsy.

3.3 Ultrasonography

The technique of ultrasound depends on the fact that different tissue textures produce sound at different frequencies, detected by a transducer; this is converted into an image, which is interpreted as a specific disease process. The use of ultrasound transducers with a frequency range of 5–7.5 MHz is usually adequate. However, improved ultrasound transducer technology has allowed the use of much higher frequencies for visualisation of breast lesions, including microcalcifications. Transducer frequencies of 12–15 MHz are now frequently employed in screening clinics as an adjunct to mammography. Lesions less than 5 mm can be detected by this method in otherwise fatty breast tissue. Ultrasound assesses the shape of the lesion by the state of its border, which can be smooth or irregular, or its contour. The latter represents the demarcation of the lesion from the surrounding tissue and can be well circumscribed or ill defined. Shadowing is caused by refraction of the sound waves, which become stronger and sharper the more vertical the lateral borders of the lesion are (Zonderland 2002

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree