Chapter 6 Recognizing a Pleural Effusion

Normal Anatomy and Physiology of the Pleural Space

Normal anatomy

Normal anatomy• The parietal pleura lines the inside of the thoracic cage and the visceral pleura adheres to the surface of the lung parenchyma, including its interface with the mediastinum and diaphragm (see Chapter 2, The Normal Frontal Chest Radiograph). The enfolds of the visceral pleura form the interlobar fissures—the major (oblique) and minor (horizontal) on the right, only the major on the left. The space between the visceral and parietal pleura, i.e., the pleural space, is a potential space normally containing only about 2-5 mL of pleural fluid.

Causes of Pleural Effusions

Fluid accumulates in the pleural space when the rate at which the fluid forms exceeds the rate by which it is cleared.

Fluid accumulates in the pleural space when the rate at which the fluid forms exceeds the rate by which it is cleared. Pleural effusions can also form when there is transport of peritoneal fluid from the abdominal cavity through the diaphragm or via lymphatics from a subdiaphragmatic process (Table 6-1).

Pleural effusions can also form when there is transport of peritoneal fluid from the abdominal cavity through the diaphragm or via lymphatics from a subdiaphragmatic process (Table 6-1).TABLE 6-1 SOME CAUSES OF PLEURAL EFFUSIONS

| Cause | Examples |

|---|---|

| Excess formation of fluid | Congestive heart failure |

| Hyponatremia | |

| Parapneumonic effusions | |

| Hypersensitivity reactions | |

| Decreased resorption of fluid | Lymphangitic blockade from tumor |

| Elevated central venous pressure | |

| Decreased intrapleural pressure | |

| Transport from peritoneal cavity | Ascites |

Types of Pleural Effusions

Pleural effusions are divided into exudates or transudates, depending on their protein content and their lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) concentrations.

Pleural effusions are divided into exudates or transudates, depending on their protein content and their lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) concentrations. Transudates tend to form when there is increased capillary hydrostatic pressure or decreased osmotic pressure, such as occurs in:

Transudates tend to form when there is increased capillary hydrostatic pressure or decreased osmotic pressure, such as occurs in:• Congestive heart failure, primarily left heart failure, which is the most common cause of a transudative pleural effusion

Side Specificity of Pleural Effusions

Diseases that usually produce right-sided effusions:

Diseases that usually produce right-sided effusions:• Abdominal disease related to the liver or ovaries—some ovarian tumors can be associated with a right pleural effusion and ascites (Meigs syndrome)

Box 6-1 Dressler Syndrome

Typically occurs 2-3 weeks after a transmural myocardial infarct producing a left pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, and patchy airspace disease at the left lung base

Recognizing the Different Appearances of Pleural Effusions

Forces that influence the appearance of pleural fluid on a chest radiograph depend on the position of the patient, the force of gravity, the amount of fluid and the degree of elastic recoil of the lung.

Forces that influence the appearance of pleural fluid on a chest radiograph depend on the position of the patient, the force of gravity, the amount of fluid and the degree of elastic recoil of the lung. The descriptions that follow, unless otherwise indicated, assume the patient is in the upright position.

The descriptions that follow, unless otherwise indicated, assume the patient is in the upright position.Subpulmonic Effusions

It is believed that almost all pleural effusions first collect in a subpulmonic location beneath the lung between the parietal pleura lining the superior surface of the diaphragm and the visceral pleura under the lower lobe.

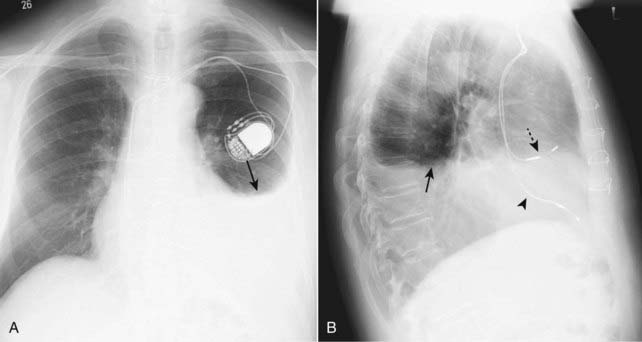

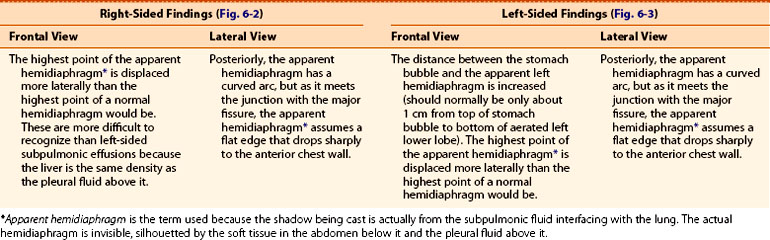

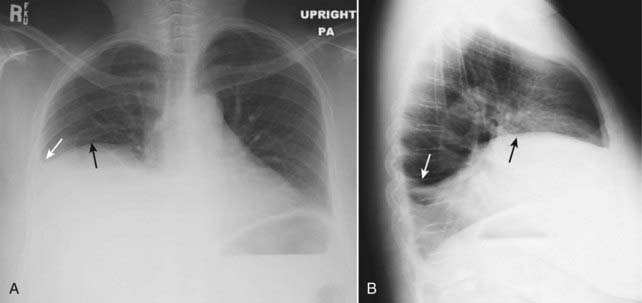

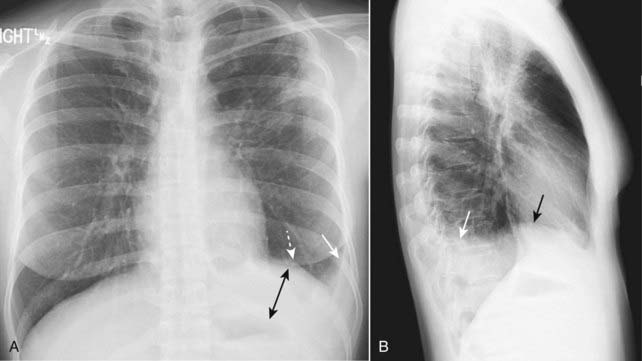

It is believed that almost all pleural effusions first collect in a subpulmonic location beneath the lung between the parietal pleura lining the superior surface of the diaphragm and the visceral pleura under the lower lobe. If the effusion remains entirely subpulmonic in location, it can be difficult to detect on conventional radiographs except for contour alterations in what appears to be the hemidiaphragm but is actually the fluid-lung interface beneath the lung.

If the effusion remains entirely subpulmonic in location, it can be difficult to detect on conventional radiographs except for contour alterations in what appears to be the hemidiaphragm but is actually the fluid-lung interface beneath the lung.