Chapter 3 Recognizing Airspace Versus Interstitial Lung Disease

Classifying Parenchymal Lung Disease

Diseases that affect the lung can be arbitrarily divided into two main categories based in part on their pathology and in part on the pattern they typically produce on a chest imaging study.

Diseases that affect the lung can be arbitrarily divided into two main categories based in part on their pathology and in part on the pattern they typically produce on a chest imaging study.Characteristics of Airspace Disease

These fluffy opacities tend to be confluent, meaning they blend into one another with imperceptible margins.

These fluffy opacities tend to be confluent, meaning they blend into one another with imperceptible margins. The margins of airspace disease are indistinct, meaning it is frequently difficult to identify a clear demarcation point between the disease and the adjacent normal lung.

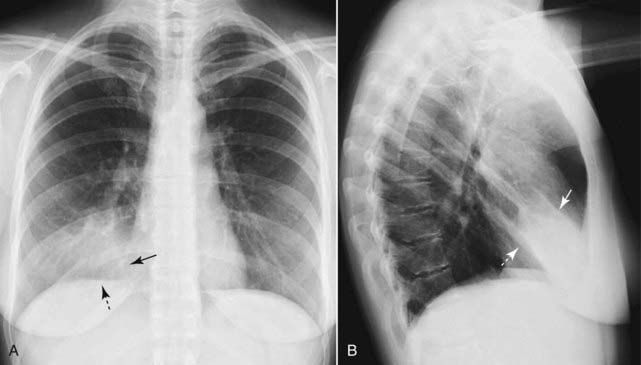

The margins of airspace disease are indistinct, meaning it is frequently difficult to identify a clear demarcation point between the disease and the adjacent normal lung. Airspace disease may be distributed throughout the lungs, as in pulmonary edema (Fig. 3-1), or it may appear to be more localized as in a segmental or lobar pneumonia (Fig. 3-2).

Airspace disease may be distributed throughout the lungs, as in pulmonary edema (Fig. 3-1), or it may appear to be more localized as in a segmental or lobar pneumonia (Fig. 3-2). Airspace disease may contain air bronchograms.

Airspace disease may contain air bronchograms.• The visibility of air in the bronchus because of surrounding airspace disease is called an air bronchogram.

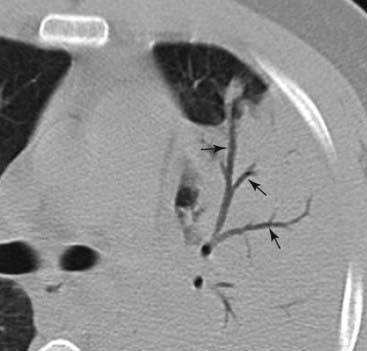

Bronchi are normally not visible because their walls are very thin, they contain air, and they are surrounded by air. When something like fluid or soft tissue replaces the air normally surrounding the bronchus, then the air inside of the bronchus becomes visible as a series of black, branching tubular structures—this is the air bronchogram (Fig. 3-3).

Bronchi are normally not visible because their walls are very thin, they contain air, and they are surrounded by air. When something like fluid or soft tissue replaces the air normally surrounding the bronchus, then the air inside of the bronchus becomes visible as a series of black, branching tubular structures—this is the air bronchogram (Fig. 3-3). What can fill the airspaces besides air?

What can fill the airspaces besides air? The silhouette sign occurs when two objects of the same radiographic density (fat, water, etc.) touch each other so that the edge or margin between them disappears. It will be impossible to tell where one object begins and the other ends. The silhouette sign is valuable not only in the chest but as an aid in the analysis of imaging studies throughout the body.

The silhouette sign occurs when two objects of the same radiographic density (fat, water, etc.) touch each other so that the edge or margin between them disappears. It will be impossible to tell where one object begins and the other ends. The silhouette sign is valuable not only in the chest but as an aid in the analysis of imaging studies throughout the body.Some Causes of Airspace Disease

Three of the many causes of airspace disease are highlighted here and will be described in greater detail later in the text.

Three of the many causes of airspace disease are highlighted here and will be described in greater detail later in the text. Pneumonia (see also Chapter 7)

Pneumonia (see also Chapter 7)• About 90% of the time, community-acquired lobar or segmental pneumonia is caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (formerly known as Diplococcus pneumoniae) (Fig. 3-5).

Pulmonary alveolar edema (see also Chapter 9)

Pulmonary alveolar edema (see also Chapter 9)• Acute alveolar pulmonary edema classically produces bilateral, perihilar airspace disease sometimes described as having a bat-wing or angel-wing configuration (Fig. 3-6).

• Pulmonary edema, which is cardiac in origin, is frequently associated with pleural effusions and fluid that thickens the major and minor fissures.

• Because fluid fills not only the airspaces but also the bronchi themselves, usually no air bronchograms are seen in pulmonary alveolar edema.

Aspiration (see also Chapter 7)

Aspiration (see also Chapter 7)• Aspiration tends to affect whatever part of the lung is most dependent at the time the patient aspirates, and its manifestations depend on the substance(s) aspirated (Fig. 3-7).

• For most bedridden patients, aspiration usually occurs in either the lower lobes or the posterior portions of the upper lobes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree