Chapter 17 Recognizing the Imaging Findings of Trauma

Trauma is the leading cause of death, hospitalization, and disability in Americans from the age of 1 year through age 45. The major imaging findings of most organ system’s trauma will be discussed as a group in this chapter. Table 17-1 summarizes some of the traumatic injuries that are discussed in other chapters.

Trauma is the leading cause of death, hospitalization, and disability in Americans from the age of 1 year through age 45. The major imaging findings of most organ system’s trauma will be discussed as a group in this chapter. Table 17-1 summarizes some of the traumatic injuries that are discussed in other chapters.TABLE 17-1 OTHER MANIFESTATIONS OF TRAUMA

| Injury | Discussed in |

|---|---|

| Pleural effusion/hemothorax | Chapter 6 |

| Aspiration | Chapter 7 |

| Pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium | Chapter 8 |

| Fractures and dislocations | Chapter 22 |

| Head trauma | Chapter 25 |

Chest Trauma

Chest injuries in trauma patients are very common and are responsible for one out of four trauma-related deaths. The overwhelming majority of chest trauma is the result of motor vehicle accidents.

Chest injuries in trauma patients are very common and are responsible for one out of four trauma-related deaths. The overwhelming majority of chest trauma is the result of motor vehicle accidents.Rib Fractures

The severity of underlying visceral injury is usually more important than the rib fractures themselves, but their presence might provide clues to unsuspected pathology.

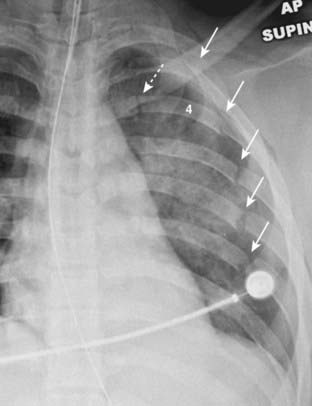

The severity of underlying visceral injury is usually more important than the rib fractures themselves, but their presence might provide clues to unsuspected pathology. Fractures of the first three ribs are relatively uncommon and, if they occur following blunt trauma, indicate a sufficient amount of force to produce other internal injuries (Fig. 17-1).

Fractures of the first three ribs are relatively uncommon and, if they occur following blunt trauma, indicate a sufficient amount of force to produce other internal injuries (Fig. 17-1). Fractures of ribs 4-9 are common and important if they are displaced (pneumothorax) or if there are two fractures in each of three or more contiguous ribs (flail chest).

Fractures of ribs 4-9 are common and important if they are displaced (pneumothorax) or if there are two fractures in each of three or more contiguous ribs (flail chest). Fractures of ribs 10-12 may indicate the presence of underlying trauma to the liver (right side) or the spleen (left side), especially if they are displaced.

Fractures of ribs 10-12 may indicate the presence of underlying trauma to the liver (right side) or the spleen (left side), especially if they are displaced. In cases of minor trauma, it is not unusual for rib fractures to be undetectable on the initial examination but to become visible in several weeks after callus begins to form.

In cases of minor trauma, it is not unusual for rib fractures to be undetectable on the initial examination but to become visible in several weeks after callus begins to form.Pulmonary Contusions

Pulmonary contusions are the most frequent complications of blunt chest trauma. They represent hemorrhage into the lung, usually at the point of impact.

Pulmonary contusions are the most frequent complications of blunt chest trauma. They represent hemorrhage into the lung, usually at the point of impact. Recognizing a pulmonary contusion

Recognizing a pulmonary contusion• The history of trauma is of paramount importance as contusions present as airspace disease that is indistinguishable from other airspace diseases like pneumonia or aspiration.

Classically, they appear within 6 hours after the trauma and, because blood in the airspaces tends to be reabsorbed quickly, disappear within 72 hours, frequently sooner.

Classically, they appear within 6 hours after the trauma and, because blood in the airspaces tends to be reabsorbed quickly, disappear within 72 hours, frequently sooner. Airspace disease that lingers more than 72 hours should raise suspicions of another process such as aspiration pneumonia or a pulmonary laceration.

Airspace disease that lingers more than 72 hours should raise suspicions of another process such as aspiration pneumonia or a pulmonary laceration.Pulmonary Lacerations (Hematoma or Traumatic Pneumatocele)

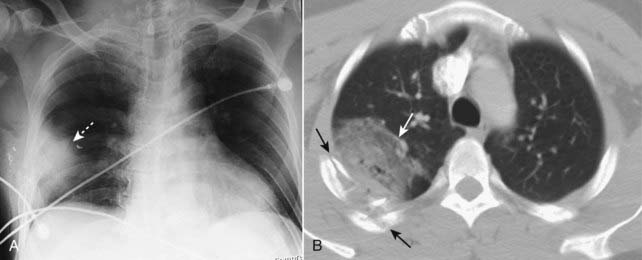

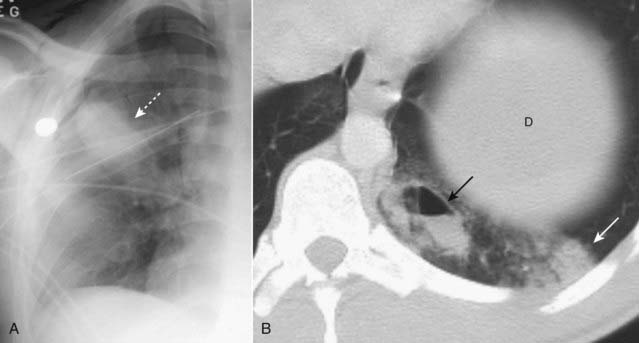

Pulmonary hematomas result from a laceration of the lung parenchyma and, as such, may accompany more severe blunt trauma or penetrating chest trauma.

Pulmonary hematomas result from a laceration of the lung parenchyma and, as such, may accompany more severe blunt trauma or penetrating chest trauma. They are sometimes masked by the airspace disease from a surrounding pulmonary contusion, at least for the first few days until the contusion resolves.

They are sometimes masked by the airspace disease from a surrounding pulmonary contusion, at least for the first few days until the contusion resolves. Recognizing a pulmonary laceration

Recognizing a pulmonary laceration• Their appearance will depend on whether they contain blood and, if so, how much blood fills the laceration.

• If they are partially filled with blood and partially filled with air, they may contain a visible air-fluid level or demonstrate a crescent sign as the blood begins to form a clot and pull away from the wall of the laceration.

Unlike pulmonary contusions that clear rapidly, pulmonary lacerations, especially if they are blood filled, may take weeks or months to completely clear.

Unlike pulmonary contusions that clear rapidly, pulmonary lacerations, especially if they are blood filled, may take weeks or months to completely clear.Aortic Trauma

Trauma to the aorta is most frequently the result of deceleration injuries in motor vehicle accidents. Although the survival rates are improving, most patients with rupture of the thoracic aorta die before reaching the hospital and, of those who survive an aortic injury, the likelihood of death increases the longer the abnormality remains untreated. Only those with incomplete tears in which the adventitial lining prevents exsanguination (producing a pseudoaneurysm) survive to be imaged.

Trauma to the aorta is most frequently the result of deceleration injuries in motor vehicle accidents. Although the survival rates are improving, most patients with rupture of the thoracic aorta die before reaching the hospital and, of those who survive an aortic injury, the likelihood of death increases the longer the abnormality remains untreated. Only those with incomplete tears in which the adventitial lining prevents exsanguination (producing a pseudoaneurysm) survive to be imaged. The most common site of injury is the aortic isthmus, which is the portion of the aorta just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery. Seat-belt injuries may involve the abdominal aorta, but such injuries are far less common than the deceleration injuries to the thoracic aorta.

The most common site of injury is the aortic isthmus, which is the portion of the aorta just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery. Seat-belt injuries may involve the abdominal aorta, but such injuries are far less common than the deceleration injuries to the thoracic aorta. Only emergency surgery will prevent approximately 50% of patients with blunt aortic injuries from dying within the first 24 hours if left untreated.

Only emergency surgery will prevent approximately 50% of patients with blunt aortic injuries from dying within the first 24 hours if left untreated. Recognizing aortic trauma

Recognizing aortic trauma• Findings seen on conventional radiographs of the chest are the same as those discussed under Aortic Dissection in Chapter 9. A completely normal chest radiograph has a relatively high negative predictive value for aortic injury, but an abnormal chest x-ray has a relatively low positive predictive value

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree