RETROPHARYNGEAL AND PREVERTEBRAL SPACE INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

KEY POINTS

- Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography provide the critical and usually definitive data needed in the diagnosis and management of retropharyngeal and prevertebral space inflammatory and infectious diseases.

- Prompt and accurate imaging can help to avoid potentially severe neurologic compromise in prevertebral infections.

- Myelography should be done reluctantly and with the greatest care if found to be necessary.

- Imaging-guided aspiration and/or tissue sampling may be used to assist in the management of these infections.

INTRODUCTION

Infections of the retropharyngeal space (RS) and prevertebral space can result in significant morbidity and mortality. Timely diagnosis and proper treatment are critical in preventing sequelae such as airway obstruction, epidural abscess and cervical cord injury, mediastinitis, carotid artery aneurysm, and cavernous sinus thrombosis.1–6

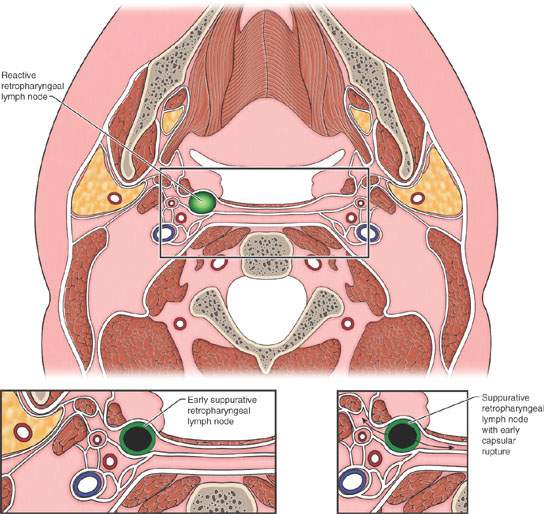

The retropharyngeal and prevertebral spaces are discussed in this chapter as the site of origin for infections and other inflammatory diseases of the head and neck. The RS is a frequent secondarily involved site in common inflammatory conditions such as infectious pharyngitis due to a wide variety of organisms, most commonly bacteria.7–18 The most common infection that comes to imaging and affects this level of the RS is retropharyngeal adenitis with or without suppuration secondary to bacterial pharyngitis. This is a disease mainly of young children. True retropharyngeal abscess, aside from that due to penetrating trauma, iatrogenic trauma, or some other cause of pharyngeal perforation, is very uncommon. Reactive RS edema is common and frequently not due to inflammation.

The prevertebral space is mainly involved by inflammatory pathology of the spine, usually discitis and/or vertebral osteomyelitis and, less commonly, tendonitis or anterior longitudinal ligament inflammation.19–24 Early differentiation of infectious disease originating from the cervical spine from that originating due to pharyngeal disease can be crucial in avoiding a catastrophic neurologic event of the cervical spinal cord.

Clinical Presentation

Infections of the retropharyngeal and prevertebral spaces are discovered because of symptoms related to the pharynx and/or spinal elements. Dysphagia or odynophagia is a common presenting complaint in adults; in infants, swallowing problems may manifest simply as “feeding difficulties.” Airway compromise is possible. Otalgia is possible. Fever is very common. The combination of fever, neck pain, and limitation of cervical spine range of motion frequently raises the clinical suspicion of meningitis.

A prevertebral space–origin infection especially may present with dominant neck pain that might be mechanical and occipital headache. Any neurologic deficit that might be due to cervical cord involvement should elevate the imaging evaluation to a very urgent or emergent status.

APPLIED ANATOMY

In the suprahyoid neck, the spaces adjacent to the visceral compartment are more numerous and structurally somewhat more complex than they are in the infrahyoid neck. In addition to the retropharyngeal and prevertebral spaces, these spaces include the parapharyngeal space (pre- and retrostyloid divisions), prevertebral space, masticator space, parotid gland within its capsule, and submandibular space (Figs. 142.3A, 147.1, 147.2, and 148.1). The parotid and submandibular glands are discussed in Chapter 175.

The primary skills necessary to interpret computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) studies of the deep spaces of the face and supra- and infrahyoid neck are common to these areas and include the following:

- Thorough knowledge of the anatomy.

- Realization that the differential diagnosis:

- Is primarily anatomically driven and largely based on analysis of the point of origin and displacement of normal anatomic structures.

- Requires a good working knowledge of neuroradiology as it relates to potential diseases of the cervical spine and spinal cord.

- Must take into account that disease may spread transcompartmentally because the process is aggressive and/or extends along existing anatomic structures (e.g., nerve, vessel, muscle bundles, and lymphatics).

- Is primarily anatomically driven and largely based on analysis of the point of origin and displacement of normal anatomic structures.

Spatial Boundaries

The RS is separated from the prevertebral space the musculofascial sheath associated with the prevertebral muscles at the level the longus colli and longus capitis (Figs. 142.3A, 147.1, 147.2, 148.1, and 148.2). The spaces come into contact directly with the posterior skull base at the craniocervical junction. The prevertebral fascia is a strong, disease-resistant interface between the prevertebral and retropharyngeal spaces with few if any areas of inherent weakness. Both are continuous across the suprahyoid and infrahyoid neck, and for these two spaces this point of division is still useful because retropharyngeal nodal pathology is relatively common and those nodes are essentially structures of the suprahyoid neck within the RS.

FIGURE 148.1. A: Anatomic section showing the relationship of the deep spaces of the suprahyoid neck. The prevertebral space is outlined in white and the retropharyngeal space (RS) in blue. The retrostyloid parapharyngeal space is outlined in red and the prestyloid parapharyngeal space in green; the masticator space is outlined in yellow. B: Sagittal section showing the relationship between the muscular pharyngeal wall (black arrow), the RS (black arrowheads), and the prevertebral musculature (white arrow) and expected position of the prevertebral fascia (white arrowhead). C: T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance study of a patient suffering neck trauma. Edema in the RS (black arrow) is posterior to the pharyngeal muscular wall (black arrowhead) and there is edema within the prevertebral muscles (white arrows) and displacement of the overlying prevertebral fascia (white arrowhead).

Structures of Interest

The analysis of a mass of the retropharyngeal and prevertebral spaces depends on a thorough understanding of their relationship to the following structures:

Superiorly: Posterior skull base in the area of the clivus

Superiorly: Posterior skull base in the area of the clivus

Inferiorly: Hyoid bone–third cervical vertebral body

Inferiorly: Hyoid bone–third cervical vertebral body

Anteriorly: Posterior pharyngeal wall

Anteriorly: Posterior pharyngeal wall

Posteriorly: Upper cervical spine and pre- and paravertebral muscles and fascia, the anterior longitudinal ligament, cervical vertebral bodies and discs, and more superiorly the lower clivus

Posteriorly: Upper cervical spine and pre- and paravertebral muscles and fascia, the anterior longitudinal ligament, cervical vertebral bodies and discs, and more superiorly the lower clivus

Medially: Not applicable

Medially: Not applicable

Laterally: Retrostyloid parapharyngeal space (RSPS) and the lateral retropharyngeal lymph nodes

Laterally: Retrostyloid parapharyngeal space (RSPS) and the lateral retropharyngeal lymph nodes

IMAGING APPROACH

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The suprahyoid neck is studied in essentially the same manner as the nasopharynx is evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and CT. The specifics and relative value of using these studies in this anatomic region are reviewed in Chapter 184. Problem-driven protocols for CT and MRI are presented in Appendixes A and B. CT should be the primary study in the vast majority of likely pharyngeal infections. MRI should be used adjunctively when a prevertebral origin is suspected and urgently or emergently if there is any question of an evolving neurologic deficit that could be related to the cervical spinal cord.

Other

Ultrasound has no significant role to play in the evaluation of these inflammatory processes, although it has been used in the past to screen for suppurative retropharyngeal adenopathy.17,18

The approach with radionuclide studies depends on the specific aim of the examination. Current usage is generally limited to bone/gallium scans for infection confirmation and related treatment surveillance as discussed in Chapter 5.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND PATTERNS OF DISEASE AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AS SEEN ON MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING AND COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

Overall Perspective

The initial evaluation of a disease process in the retropharyngeal and prevertebral spaces must determine whether those spaces might be only secondarily involved by a mucosal disease or due to a transspatial process arising deep to the mucosa in the spaces of the suprahyoid neck, of the cervical spine, or in the skull base (Figs. 148.2 and 148.3). Transspatial disease may also begin in the RS (Fig. 148.4). Infections are inherently capable of transspatial spread. The mechanisms and potential routes of transspatial spread in these infections are by direct perforation, perforation along areas of inherent weakness, or spread along or within arteries and veins that cross from one space to another, this typically by infectious thrombophlebitis in pyogenic infections. For aggressive pathologies such as discitis and vertebral osteomyelitis, transspatial spread is a simple morphologic spread pattern to understand; however, it is uncommon for the prevertebral space to spread to the RS because of the barrier provided by the prevertebral fascia except for disease-related edema.

FIGURE 148.2. A: Illustration showing how edema appears to spread in the retropharyngeal and paravertebral spaces, respectively. B: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) study showing retropharyngeal edema (arrows) due to jugular vein thrombosis. C: Contrast-enhanced CT study showing generalized changes throughout the larynx and neck related to edema from radiotherapy, including thickening of the superficial fascia (white arrow) and deeper neck soft tissue planes (arrowheads). Retropharyngeal space edema (black arrow) is commonly seen following radiotherapy. D: A patient suffering trauma showing secondary retropharyngeal edema (arrows). The prevertebral hematoma is relatively distinct from the retropharyngeal hematoma and is seen spreading in the epidural space as well as the prevertebral space (arrowheads). E: Sagittal image of the patient in (D) showing the epidural blood and generalized thickening of the prevertebral and retropharyngeal soft tissues that cannot be differentiated from one another. Extension of this process in a fairly typical fashion toward the clivus (arrowhead) is present. F, G: Studies on a patient suffering neck trauma. In (F), the plane film shows very extensive swelling of the prevertebral and retropharyngeal soft tissues without obvious bony injury. In (G), a correlating CT study shows the prevertebral and retropharyngeal soft tissue swelling (arrows) and a small epidural hematoma (arrowhead). H: Contrast-enhanced axial CT image showing how posttraumatic prevertebral edema and retropharyngeal edema tend to collect more in the midline (arrows). There is loss of definition of soft tissues within the prevertebral space, but this is difficult to distinguish from normal muscular structures (arrowheads). (NOTE: In this case, contrast was given as part of a posttrauma CT angiographic study.)

Developmental considerations occasionally come into play in these inflammatory conditions of the RS since a fistula or cyst can provide a route of spread.

Differential Diagnosis

The method of differential diagnosis is driven by an orderly process of relatively simple observations that may be made on the basis of MR and/or CT studies (Tables 147.2 and 147.3). The process may be supplemented by imaging-directed aspiration and/or tissue sampling, which is very safe and effective in this region, especially when compared to what it takes to secure a surgical sample (Chapter 6). The suggested process is as follows:

- Determine whether the process involves single or multiple spaces.

- If single, determine which space is involved. In this chapter, it would be centered in the retropharyngeal or prevertebral spaces based on making the following observations with regard to vectors of structural displacement and spread of the inflammatory process (Figs. 148.2–148.10).

- Superiorly, the process will approach or come from the posterior skull base in the vicinity of the clivus.

- Inferiorly, the spreading inflammation will track to or below the level of the hyoid bone.

- Laterally, the fat between the RS and RSPS will be infiltrated directed by fascial attachments that extend toward the carotid sheath from the RS inflammation but usually will be confined by the prevertebral attachments laterally in prevertebral space–origin inflammatory diseases.

- Medially, the process will occupy the midline or a paramedian position in the essentially midline RS and may be contained even more in the midline somewhat contained by the prevertebral muscles in prevertebral space–origin processes.

- Anteriorly, the process will displace and/or infiltrate the posterior muscular wall of the pharynx if it is primarily of RS origin, and it will displace the anterior longitudinal ligament and prevertebral fascia and possibly the prevertebral muscles if of prevertebral space, spinal origin.

- Posteriorly, it may involve the lower clivus and/or the prevertebral space or upper cervical spine. If of prevertebral space origin, it may involve the paravertebral space, discs, vertebral bodies, and epidural space.

- Superiorly, the process will approach or come from the posterior skull base in the vicinity of the clivus.

- Observations regarding the morphology of the presumptive inflammatory process (Chapters 13 and 16) may require both MRI and CT for a comprehensive evaluation, especially when the prevertebral space is the focus of the disease process, while CT alone is typically adequate in pharyngeal-origin infections.

- Identification of associated findings such as lymphadenopathy, epidural disease, discitis, or anterior longitudinal ligament calcification (Fig. 148.10).

FIGURE 148.3. Several patients with retropharyngeal edema due to processes starting outside the retropharyngeal space (RS). A: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) study of a patient with severe pharyngitis and edema spreading throughout the RS (arrows) and surrounding the pharyngeal plexus of vessels commonly present at the C3 level (arrowheads). B: Contrast-enhanced CT of a patient with discitis more on the right side. The retropharyngeal edema is seen predominately on the right (white arrow) compared to the more normal fat on the left (white arrowhead). The prevertebral origin is somewhat more apparent when considering the loss of tissue planes in the prevertebral space on the right (black arrows) compared to those normal planes on the left. C: Contrast-enhanced CT of a patient with pharyngitis and secondary retropharyngeal edema (arrow) with spread into the prevertebral and paravertebral spaces (arrowheads). D: Contrast-enhanced CT in a diabetic patient with a severe necrotizing infection. This necrotizing infection has spread secondarily throughout the floor of the mouth, tongue base, and submandibular space. It produced secondary retropharyngeal edema (white arrows). E: Contrast-enhanced CT of a patient having had recent adenoidectomy and with evidence of a pharyngeal abscess. The abscess spread across the surgically violated pharyngeal wall to produce edema and gas in the RS (arrows), possibly crossing into the prevertebral space (arrowhead). F: Patient with skull base osteomyelitis with loss of tissue planes in the prevertebral retropharyngeal spaces. G: Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image in a patient with skull base osteomyelitis spreading inferiorly from the clivus along the carotid artery (white arrow) and mainly within the prevertebral space (white arrowheads). The fat in the RS is largely spared.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree