RETROPHARYNGEAL AND PREVERTEBRAL SPACE MASSES

KEY POINTS

- Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography provide the critical and usually definitive data needed in the diagnosis and management of retropharyngeal space and posterior compartment masses.

- Prompt and accurate imaging can help to avoid potentially severe neurologic compromise in the pathology of the posterior compartment.

- Myelography should be done reluctantly and with the greatest care if found to be necessary.

- Computed tomography–guided tissue sampling may be useful in the management of these masses.

INTRODUCTION

The retropharyngeal space (RS) and prevertebral space are discussed in this chapter as the site of origin of mass lesions of the infrahyoid neck when the lesion arises at their interface. The posterior compartment, containing the prevertebral space as one of its components, is mainly involved by inflammatory and neoplastic pathology of the spine but is sporadically the primary site of mass lesion origin. Other conditions of the posterior compartment are discussed in Chapters 160 through 162.

The RS is a common secondarily involved site in common inflammatory conditions such as suppurative retropharyngeal adenitis and the very uncommon true retropharyngeal abscess as well as mucosal-origin neoplastic conditions such as oropharyngeal cancers that are discussed in other chapters. The spectrum of disease that might arise in the RS and posterior neck compartment (prevertebral and paravertebral spaces) is outlined in Table 152.1. This chapter considers those that appear as mass lesions.

Clinical Presentation

The primary presentation may be that of a palpable neck mass of uncertain etiology without associated signs or symptoms or other physical findings. That presentation was discussed in Chapter 150. There may be associated pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, or dysphonia. Airway compression is possible. Occasionally, there will be a history of the mass changing in size, sometimes intermittently.

Tenderness and fever and associated generalized swelling may be present and is much more likely in inflammatory conditions. Benign and vascular masses may be compressible and/or pulsatile. Masses may feel obviously cystic to palpation.

Neurologic dysfunction may be due to involvement of the cervical sympathetics, vagus nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerve, and phrenic nerve. Signs of cervical spinal cord compromise, when present, may suggest that a very urgent problem is at hand.

APPLIED ANATOMY

The anatomy of interest is discussed in detail in Chapter 149 and summarized in Chapter 150 with regard to its application in evaluating neck masses.

IMAGING APPROACH

The techniques for computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) studies of the infrahyoid neck for various clinical situations are presented in Appendixes A and B.

Standard ultrasound imaging and flow-related techniques are used with transducers appropriate for the depth of penetration required. The rationale for these protocols is presented specifically in Chapter 149.

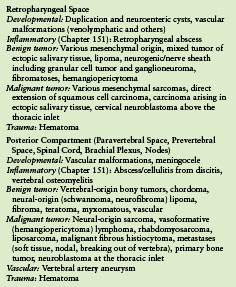

TABLE 152.1. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF NECK MASSES BY SPACE/COMPARTMENT OF ORIGIN

The approach with radionuclide studies depends on the specific aim of the examination. Most current usage is limited to known or suspected cancer evaluation with fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and bone/gallium scans for inflammatory pathology; both are discussed in other chapters. The use of FDG-PET should be extremely limited in these masses since the diagnosis will be established by a combination of imaging and tissue sampling.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND PATTERNS OF DISEASE AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AS SEEN ON MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING AND COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

The initial evaluation of a mass involving the retropharyngeal or prevertebral space must determine whether there might be only secondary involvement due to a mucosal disease or a transspatial process arising deep to the mucosa in the spaces of the infrahyoid neck, of the cervical spine, or in the skull base. Transspatial disease may begin in the RS and occasionally the posterior compartment. Transspatial processes are, regardless of space of origin, masses that arise primarily in the deep spaces of the neck. The mechanisms and potential routes of transspatial spread vary. For aggressive pathologies such as cancers or discitis and vertebral osteomyelitis, transspatial spread is a simple morphologic spread pattern to understand. It is also a fairly intuitive pattern to understand in developmental abnormalities that affect these spaces. For instance, since venolymphatic malformations grow due to disordered vascular budding, they simply follow vessels as those vessels would normally traverse various compartments or spaces of the suprahyoid neck. In the case of the retropharyngeal and prevertebral spaces, such developmental knowledge also helps to predict how nerve sheath tumors extend across spatial boundaries.

Differential Diagnosis

The method of differential diagnosis is driven by an orderly process of relatively simple observations that may be made on the basis of MR and/or CT studies (Table 150.1). The process may be supplemented by imaging-directed biopsy, which is very safe and effective in this region especially when compared to what it takes to secure a surgical sample (Chapter 6). The suggested process is as follows:

- Determine whether the process involves single or multiple spaces.

- If single, determine which space is involved. In this chapter, it would be centered in the retropharyngeal or prevertebral space based on making the following observations with regard to vectors of structural displacement and “travel” of the mass.

- Laterally, the fat between the RS and carotid sheath will be compressed, and lateral spread in posterior compartment masses will be confined by the tough pre- and paravertebral fascial layer.

- Medially, the process will occupy the midline or a paramedian position in the essentially midline RS and may be contained primarily in the midline somewhat contained by the prevertebral muscles in prevertebral space–origin processes.

- Anteriorly, the process will displace and/or invade the posterior muscular wall of the pharynx if it is primarily of RS origin and will displace the anterior longitudinal ligament and prevertebral fascia and possibly the prevertebral muscles if of prevertebral space/spinal origin.

- Posteriorly, it will respect the plane of the prevertebral fascia if of RS origin. If of prevertebral space origin, it may involve the paravertebral space and its musculature, discs, vertebral bodies, and epidural space.

- Laterally, the fat between the RS and carotid sheath will be compressed, and lateral spread in posterior compartment masses will be confined by the tough pre- and paravertebral fascial layer.

- Observations regarding the likely aggressiveness of margins of the mass and its internal morphology (Chapters 21 and 22) are typically more comprehensively demonstrated on MR images.

- Identification of associated findings such as lymphadenopathy, epidural disease, discitis, or tendon and ligament calcification are important additive factors.

Relative Frequency of Pathology

All of these masses are relatively rare and sporadic.

Imaging Appearance

The morphology and spread pattern of lesions identified in Table 152.1 are discussed in the following figures and chapters in Section 2:

For Both the RS and Posterior Compartment

- Venolymphatic and other vascular malformations (Fig. 152.1 and Chapter 9)

- Mesenchymal benign tumors (Fig. 152.2), sarcomas (Fig. 152.3 and Chapters 35–37), and vasoformative tumors (Chapter 25)

- Nerve sheath (Figs. 152.4 and 152.5) and other neurogenic (Fig. 152.6) tumors (Chapters 29 and 30)

- Lipogenic tumors (Chapter 36)

FIGURE 152.1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography study in a patient presenting with multiple compressible neck masses. One of these is in the retropharyngeal space (arrow) and another is in the lateral compartment on the right (arrowhead). These were multiple venolymphatic malformations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree