RETROPHARYNGEAL AND VISCERAL COMPARTMENT INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

KEY POINTS

- Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography provide the critical and usually definitive data needed in the diagnosis and management of retropharyngeal space inflammatory and infectious diseases.

- Prompt and accurate imaging can help to avoid potentially severe airway problems and/or spread to the mediastinum.

- Imaging-guided aspiration and/or tissue sampling may be used to assist in the management of these infections.

INTRODUCTION

Infections of the visceral compartment and retropharyngeal space (RS) discussed in this chapter, as well as those of the posterior compartment and related prevertebral space and paravertebral space discussed in Chapter 160, can result in significant morbidity and mortality. To some extent, these anatomic locales of infection might be considered together since their imaging picture may overlap; however, the conditions most often diverge considerably based on their clinical presentation. Timely diagnosis and proper treatment are critical in preventing sequelae such as life-threatening airway obstruction, epidural abscess and cervical cord injury, mediastinitis, carotid artery aneurysm, and cavernous sinus thrombosis.1–6

The visceral compartment and related RS are discussed in this chapter as the site of origin of infections and other inflammatory diseases of the head and neck. The RS at the infrahyoid neck level is commonly affected by inflammatory conditions such as infectious pharyngitis due to a wide variety of organisms, most commonly bacteria, with those infections manifesting mainly variable amounts of RS edema7–16 (Fig. 151.1). Infrahyoid RS and retropharyngeal abscesses may be due to a complication of bacterial pharyngitis, penetrating trauma, iatrogenic trauma, or some other cause of pharyngeal perforation (Figs. 151.2–151.5). RS abscess is rarely due to extension of a prevertebral space or other deep neck abscess. Reactive RS edema is often due to causes other than infection (Fig. 151.6).

Infectious disease originating from the cervical spine (Chapter 160) must be differentiated early in the diagnostic process from that originating due to pharyngeal disease to avoid a potentially catastrophic neurologic event involving the cervical spinal cord.

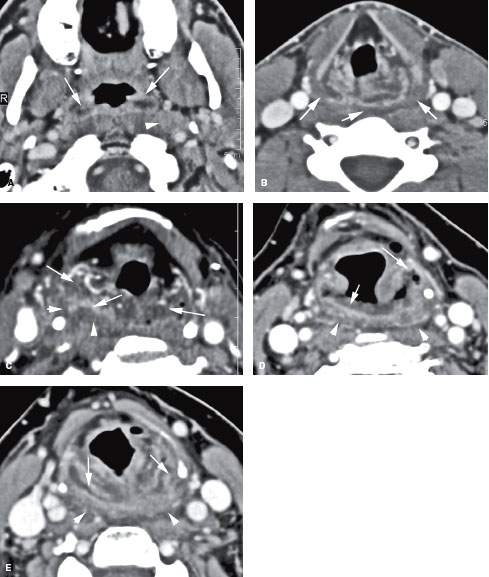

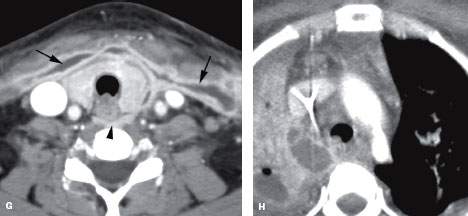

FIGURE 151.1. Three patients with pharyngitis of different causes to demonstrate pharyngeal infections that result in only reactive retropharyngeal space (RS) edema. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography images are shown in all patients. A, B: Patient 1 with bacterial pharyngitis manifesting as mucosal enhancement and edema (arrows) at the junction of the oropharynx and nasopharynx and a retropharyngeal reactive lymph node (arrowhead)—all seen in (A). In (B), there is extensive edema and enhancement within the hypopharynx resulting in bilateral retropharyngeal edema (arrows). C: Patient 2 with pharyngitis due to tuberculosis. Primary pharyngeal infection is manifest by edema and mucosal enhancement (arrows), while the retropharyngeal edema has no surrounding enhancement and does not involve the prevertebral space (arrowhead). D, E: Patient 3 with aggressive Candida inflammation of the pharynx. The pharyngeal infection is manifest in (D) by ulceration, mucosal enhancement and edema within the pharyngeal wall (arrows), and edema spreading in the RS (arrowheads).

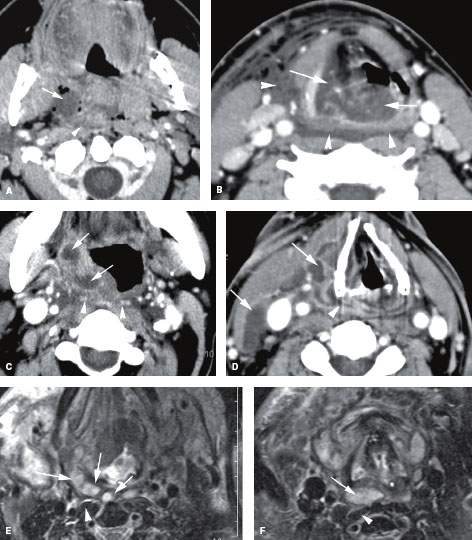

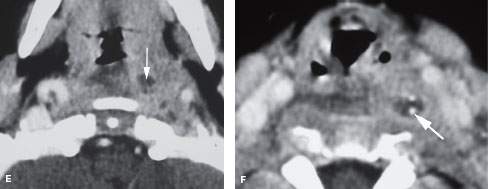

FIGURE 151.2. Two patients with aggressive pharyngeal infections resulting in retropharyngeal edema or possible abscess. A, B: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography studies in Patient 1 with diabetes, who developed a severe necrotizing anaerobic tonsillar infection. In (A), at the level of the oropharynx, there is a tonsillar abscess extending into the parapharyngeal space (arrow) with evidence of either edema or abscess spreading into the retropharyngeal space (RS) (arrowhead). Necrotizing infections, especially in diabetic patients, sometimes make it difficult to separate edema from spreading necrotic infected material. In (B), the extensive edema of the supraglottic larynx (arrowheads) severely compromises the laryngeal airway (arrows). Edema is seen spreading throughout the RS and from it into the lateral compartment of the neck (arrowheads). (NOTE: Drainable pus in this patient was limited to the region of the tonsil and immediately adjacent to the RS, as shown in [A]. Necrotic tissue and purulent material were evacuated from that level.) C, D: Immune-compromised Patient 2, with an aggressive spreading tonsillar infection. In (C), a multiloculated infection within the tonsil and oropharyngeal wall (arrows) produces fairly severe retropharyngeal edema (arrowheads). In (D), a section through the mid neck shows that the infection has spread within the visceral compartment and lateral compartment, producing multiple areas of loculated pus (arrows). These changes within the visceral compartment wrap around the attachment of the constrictor muscles to the larynx and produce an infection spreading within the pharyngeal wall but only a small amount of retropharyngeal edema. (NOTE: Surgery confirmed pus within the visceral compartment and deep neck but none in the RS.) E, F: T2-weighted magnetic resonance images showing an extensive neck abscess including a retropharyngeal component. In (E), the multiloculated tonsillar abscess spreads to the RS (arrows), sparing the prevertebral space and muscles (arrowhead) except for perhaps the most minimal amount of prevertebral space edema. In (F), a section through the mid neck shows the loculated pus in the RS (arrow) and some edema surrounding the longus colli muscle (arrowhead). This only represents minimal prevertebral space reactive edema, illustrating the relative resistance of the prevertebral fascia to spread of purulent material.

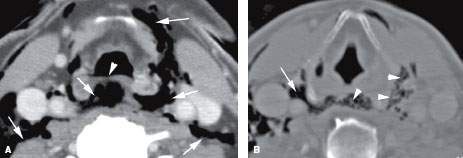

FIGURE 151.3. A patient with severe pharyngitis that produced a retropharyngeal abscess and mediastinitis. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography was done. A: Purulent material is seen spreading to the level of the hyoid within the retropharyngeal space (RS) (arrowheads), while only edema is seen within the pharynx (arrows). This was the approximate upper level of the retropharyngeal abscess. B: Purulent material spreads extensively within the visceral compartment (arrows) and is loculated in the RS (arrowheads). C: In the low neck, purulence spreads within the visceral compartment and into the lateral compartment (arrows). There is little identifiable abnormality in the RS. D: At the thoracic inlet, pus is again visible in the RS (arrow); in (E), the large mediastinal abscess is visible. The patient remained febrile following antibiotic therapy. F, G: Follow-up study was done. In (F), a small amount of purulent material remains loculated in the RS (arrow); in (G), the purulent material can be seen tracking into the lateral compartment of the neck along the layers of the investing layer of cervical fascia. H: The mediastinal abscess was smaller but is still present. (NOTE: Retropharyngeal abscesses that are very conspicuous may become relatively inconspicuous at the thoracic inlet, again blossoming in the mediastinum, as seen in this case.)

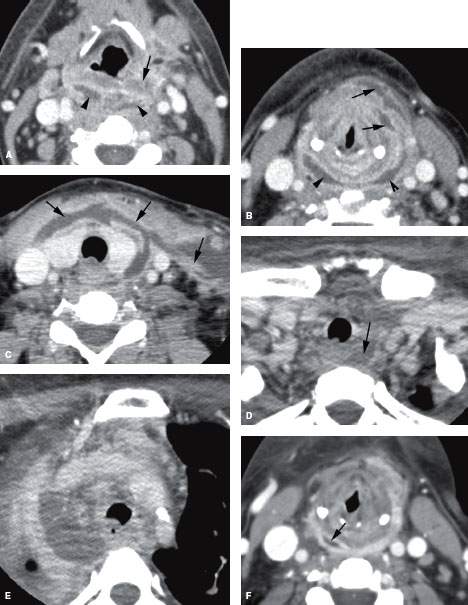

FIGURE 151.4. A–D: Patient 1 presenting with fever and neck pain. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was done. In (A), a planning digital radiograph from the CT study shows marked widening of the prevertebral soft tissues (arrowhead) and a possible foreign body (arrow). In (B), the loculated retropharyngeal abscess (black arrowhead) was caused by a chicken bone (black arrow). The prevertebral fascia is likely enhancing along with the wall of the abscess (white arrowheads). The prevertebral space is not involved. In (C), this abscess dissected inferiorly, with the lowermost portion of the loculated abscess extending to about the mid portion to the lower pole of the thyroid gland but not entering the mediastinum. In (D), the upper portion of the abscess ends at about the hyoid bone level. Note that the fluid collection at this level (arrows) has a rim of enhancement, differentiating retropharyngeal edema from the abscess present in this case. E, F: Patient 2, who was suffering a perforating pharyngeal injury. Perforation was at the level of the tonsil. This child jammed a pencil into the back of his throat. At the tonsillar level, only a small collection of pus was noted (arrow). In (F), the related foreign body, which was surgically proven to be a pencil point, was found much lower in the abscess cavity, having migrated inferiorly (arrow).

Clinical Presentation

Infections of the retropharyngeal and prevertebral spaces are often discovered because of symptoms related to the pharynx. Dysphagia or odynophagia is a common presenting complaint in adults; in infants, swallowing problems may manifest simply as “feeding difficulties.” Airway compromise is possible. Otalgia is possible. Fever is very common. The combination of fever, neck pain, and limitation of cervical spine range of motion in a patient with RS abscess may mimic meningitis.

APPLIED ANATOMY

In the infrahyoid neck, the anatomy related to the visceral compartment and surrounding compartments and spaces is less complex than in the suprahyoid neck.

The prevertebral fascia is thick and relatively resistant to the spread of pathologic processes compared to the fascia of the visceral compartment. This provides a relatively resistant barrier to spread of pus between the prevertebral space and RS, although reactive edema spreads readily from one space to another. The musculofascial sheath associated with the prevertebral longus colli muscles forms the prevertebral fascia; this deep layer of cervical fascia then reflects laterally over the vertebral transverse processes and the attachments of the scalene muscles to cover the paravertebral muscles that make up the bulk of the posterior compartment of the neck as discussed in Chapters 142 and 149 (Figs. 142.3A, 149.1, and 149.2).

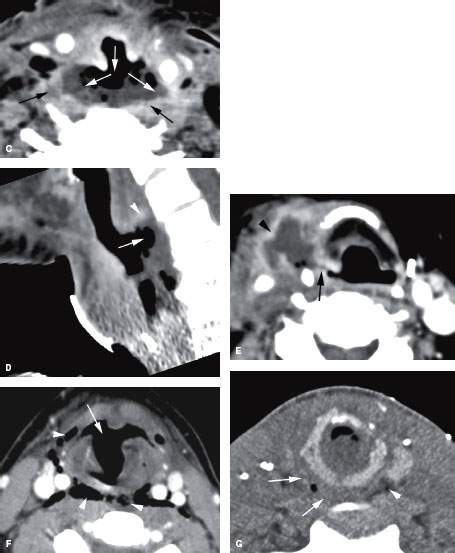

FIGURE 151.5. Several patients with false passages or penetrating injuries showing the potential for spread of purulence within the visceral compartment and retropharyngeal space (RS). A, B: Patient 1, who is suffering an upper pharyngeal perforation during intubation. The area of perforation is seen at the junction of the oropharynx and hypopharynx (arrowhead). Air dissects throughout the RS and retrovisceral space, communicating with the lateral compartment and showing the demarcation between these spaces and the prevertebral spaces. In (B), the air is again seen within the RS and dissecting into the lateral compartments and visceral compartment (arrowheads). Septae can be seen within these spaces, accounting for some of the fibrofatty tissue that might alter spread patterns and/or contribute to loculation of purulent material. An extension into the lateral neck toward the carotid sheath on the right shows that the RS is in direct continuity with the lateral compartment of the neck and intimately related to the carotid sheath (arrow). C, D: Patient 2 with a reconstructed pharynx presenting with fever and neck pain. In (C), there is a very large perforation of the neopharynx communicating with the RS (white arrows), and purulent material and gas is present. The walls of the collection are enhancing (black arrows), which is consistent with the large retropharyngeal abscess that does not extend into the prevertebral space, but there is fairly marked enhancement along the prevertebral fascia and prevertebral muscles, reflecting reactive change at that interface. In (D), a sagittal view shows the depth of the abscess cavity (arrow) and related wall enhancement. With this depth of penetration, it is not surprising that reactive change is present in the prevertebral space. E: Patient 3, who had a neck dissection and subsequently developed an infection deep to the flap used to close the surgical bed. The abscess collects within the lateral neck and has a thick enhancing wall (arrowhead). The source of the infection was a fistula (arrow) from the right pyriform sinus. This was confirmed surgically. F: Patient 4, who was suffering severe laryngeal trauma. There is a large false passage anteriorly in the larynx (arrow), and the arrowheads demonstrate a potential pass of communication between the larynx and pharynx and RS (arrowheads). A small amount of fluid and debris is seen in the midline of the RS. F: Patient 5, who was suffering a gunshot wound to the neck. There is gas and edema in the RS on the right side, which is consistent with a wound that has caused communication with the airway or pharynx (arrows). Note the edema in the RS on the right (arrows) compared to the normal fat on the left (arrowheads). The course of the bullet fragments producing the comminuted cricoid fracture is also seen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree