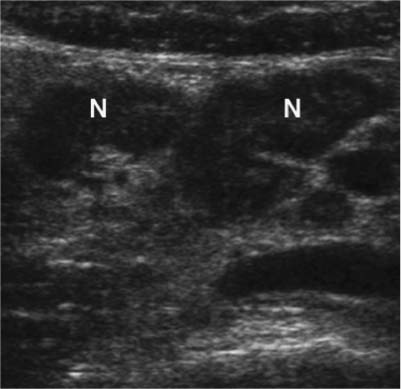

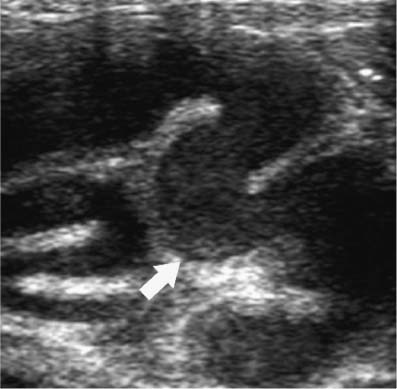

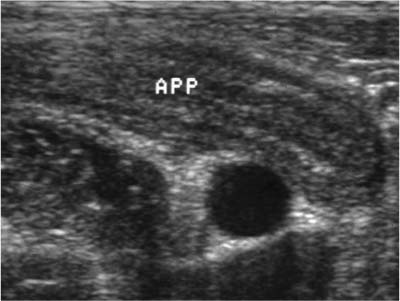

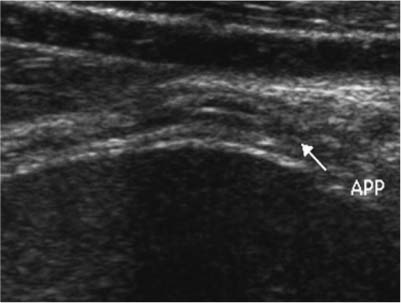

8 Right Lower Quadrant Pain: Ruling Out Appendicitis Although the incidence of appendicitis appears to be declining slightly in the Western world, it nonetheless remains the most common cause of acute abdominal pain requiring surgery.1,2 In the United States each year, ~250,000 patients undergo appendectomies for presumed appendicitis.1,2 The differential diagnosis 1of acute appendicitis is extremely broad, and appendicitis often mimics the presentation of many other gastrointestinal, genitourinary, or gynecologic abnormalities. Historically, clinical misdiagnosis is common; ~20% of patients presumed to have appendicitis undergo a nontherapeutic laparotomy with removal of a normal appendix. The rate of negative appendectomy is even higher in women of reproductive age, in whom 30 to 40% of surgeries yield normal appendices.3,4 Surgeons have traditionally relied almost entirely on the patient’s history and physical examination to determine the need for surgery.1–13 However, during the past decade imaging studies have played an increasingly important role in the diagnostic evaluation of patients with possible appendicitis.8,9 Several large clinical series have documented a high degree of sensitivity and specificity for computed tomography (CT) and sonography in the evaluation of patients with right lower quadrant pain and possible acute appendicitis.8,9 The accurate noninvasive imaging of acute appendicitis now makes obsolete the complete reliance upon the patient’s history and physical examination to determine the need for surgery. Figure 8–1 Mesenteric adenitis. Note multiple enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes (N) on sagittal sonogram of right lower quadrant in a patient with a normal appendix (not shown). In patients with acute right lower quadrant pain, appendicitis is only one of a large number of gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and gynecologic disorders. Common clinical mimics of acute appendicitis include mesenteric adenitis (Fig. 8–1), ureteral calculi, right-sided diverticulitis, acute gynecologic disorders, and viral gastroenteritis. In his classic monograph on the early diagnosis of the acute abdomen, Sir Zachary Cope listed 34 different disorders that may clinically mimic acute appendicitis.13 This list has greatly expanded in the past several decades, with advances in medical knowledge and newer disease entities, such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), associated with immunosuppressive states. One factor contributing to the overall complexity of acute right lower quadrant pain as a clinical problem is that the differential diagnosis ranges from benign self-limited disorders (e.g., mesenteric adenitis or viral gastroenteritis) to lesions that carry significant morbidity if not treated promptly, including bowel obstruction, perforation, infarction, or abscesses of various etiologies. Figure 8–2 Pelvic inflammatory disease. Transverse sonogram of right lower quadrant demonstrates dilated and tortuous fallopian tube (arrow) containing intraluminal low-level echoes representing pus. In women of reproductive age, it is often difficult to clinically differentiate appendicitis from acute gynecologic disorders. Pelvic inflammatory disease (Fig. 8–2), degenerating myomas (Fig. 8–3), ovarian torsion, and ruptured or hemorrhagic functional cysts may all mimic the clinical presentation of acute appendicitis at times.4 In patients over 50 years of age, perforated cecal neoplasm should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.14 The “classic history” for acute appendicitis is the onset of diffuse abdominal or midepigastric pain that after a period of time localizes to the right lower quadrant.1,2 Pain is frequently accompanied by anorexia and at times nausea and vomiting. Of note is the fact that this classic history is present in only 55% of patients with acute appendicitis.2 The most characteristic physical finding is guarding and rebound tenderness over the McBurney point in the right iliac fossa. The early diagnosis of acute appendicitis is often difficult in pediatric patients due to problems in obtaining an adequate history. Some elderly or immunocompromised patients may have relatively minimal pain with acute appendicitis. Figure 8–3 Degenerating myoma in pregnancy. Transverse color Doppler sonogram demonstrates avascular myoma in patient with 20 week gestation. The location of the appendiceal tip is highly variable and may be a major factor in contributing to the patient’s symptoms and localization of pain. Flank pain may be the most striking finding in a patient with a retrocecal appendix that extends along the right lateral flank. In patients with a pelvic appendix, suprapubic tenderness or deep pelvic pain may be the most predominant clinical symptom. In female patients, this may closely mimic symptoms of salpingitis, ovarian torsion, or other acute gynecologic abnormalities. Endovaginal sonography may be quite useful to demonstrate pelvic appendicitis in women (Fig. 8–4). Laboratory values in appendicitis are highly variable and often nonspecific.15 Although leukocytosis with left shift is common, up to one third of adult patients with acute appendicitis have a normal leukocyte count.15 Elderly patients, in particular, are known to have relatively normal laboratory values with acute appendicitis. A high fever with leukocytosis is characteristic of, but not always present with, a periappendiceal abscess. Although it seems reasonable that patients with clear-cut clinical evidence of acute appendicitis be managed surgically without preoperative imaging, patients with atypical presentations and patients who are poor surgical candidates can benefit from preoperative imaging.16 Due to the extensive differential diagnoses in women of child-bearing age, including numerous gynecologic entities for right lower quadrant pain, these patients benefit most from preoperative imaging. Bendeck et al showed that the negative appendectomy rate was significantly lower (8 vs 28%) in women who underwent preoperative sonography versus those who had no pre-operative imaging.16 Other studies have also documented a reduction in the negative appendectomy rate with pre-operative imaging.17 Figure 8–4 Pelvic appendicitis on endovaginal color Doppler sonogram. Note dilated appendix (arrow) with mural hyperemia. Figure 8–5 Early acute appendicitis. Enlarged noncompressible appendix (APP) is noted anterior to external iliac artery (A) and iliopsoas muscle (M). Graded compression sonography is based on the principle that when pressure is applied to a normal bowel loop with a transducer, it will readily compress.9 Any inflammatory or neoplastic process infiltrating the bowel wall alters its compliance, making it relatively noncompressible. Whenever possible, it is important to use the highest-resolution linear array transducer that affords adequate penetration to visualize the key anatomical landmarks of the psoas muscle and external iliac artery and vein (Fig. 8–5). The study should be considered nondiagnostic if these normal structures cannot be visualized. In general, a 6 to 8 MHz linear or curved array transducer is adequate for most pediatric and adult patients. Endovaginal sonography is a valuable tool in female patients of reproductive age to evaluate the adnexal areas and detect pelvic appendicitis.18 At the outset of the examination, the patient is asked to point with a single finger to the site of maximal pain or tenderness. This maneuver is often helpful in identifying a potentially aberrantly located appendix. Sonographic imaging is then initiated in the transverse plane using light pressure to first identify the abdominal wall musculature and the right colon. The right colon is the largest structure in the right flank with the typical sonographic bowel signature (echogenic submucosal layer) that has no peristalsis. The right colon is then followed caudally to its termination as a cecal tip. Pressure is gradually applied to the cecal tip to express all the gas and fecal contents from its lumen and enhance visualization of the noncompressible appendix. It is very important to vary the acoustic window to obtain the optimal view to demonstrate the appendix. Sometimes, as in the setting of a deep pelvic appendix, a full urinary bladder can be used as an acoustic window to visualize an otherwise inaccessible appendix. This technique, however, obviates graded compression. In the situation of a retrocecal appendix, placing the patient in a left lateral decubitus position may aid visualization by displacing the cecum and terminal ileum medially. With the patient in this position, scanning the right flank can sometimes be helpful by reducing the transducer–target distance. Finally, in women of childbearing age, transvaginal sonography can play an important role in the visualization of a pelvic appendix or in the identification of alternative diagnoses. In one study of sonographically detected appendicitis, transabdominal sonography detected 76% of cases, whereas transvaginal sonography added 24%.18 Figure 8–6 Normal appendix visualized by sonography. Appendix (APP) is identified in its long axis with maximal diameter of 5 mm. Although other published reports have suggested that the normal appendix can be visualized in a high percentage of patients (Fig. 8–6), the point is somewhat controversial.19

Differential Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

Diagnostic Evaluation

Ultrasound

Imaging

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree