, Mark J. Jameson2, Max Wintermark3 and Sugoto Mukherjee4

(1)

Division of Neuroradiology, Department of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

(2)

Division of Head and Neck Surgical Oncology, Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

(3)

Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

(4)

Division of Neuroradiology, Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

Abstract

The salivary glands may be afflicted by a wide variety of inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic processes. This often creates difficulty in arriving at a specific imaging diagnosis. Knowledge of glandular anatomy and pertinent clinical data is vital to the radiologist to arrive at a reasonably short list of differential diagnoses and provide information that is of importance to the otolaryngologist for surgical planning. This chapter discusses basic salivary gland anatomy and imaging appearances of the more common glandular disorders and also provides a table of differential diagnosis based on pattern recognition. A brief section that discusses the otolaryngologist’s approach to the evaluation of salivary gland disease is also included.

6.1 Introduction

The salivary glands may be afflicted by a wide variety of inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic processes. This often creates difficulty in arriving at a specific imaging diagnosis. Knowledge of glandular anatomy and pertinent clinical data is vital to the radiologist to arrive at a reasonably short list of differential diagnoses and provide information that is of importance to the otolaryngologist for surgical planning. This chapter discusses basic salivary gland anatomy and imaging appearances of the more common glandular disorders and also provides a table of differential diagnosis based on pattern recognition. A brief section that discusses the otolaryngologist’s approach to the evaluation of salivary gland disease is also included.

6.2 Anatomy

Box 6.1 summarizes a summary of glandular anatomy, ductal and lymphatic drainage.

The parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands are the major paired glandular structures. Up to 750 minor salivary gland clusters exist in the upper aerodigestive tract, paranasal sinuses, and parapharyngeal spaces.

The parotid gland is divided into superficial and deep lobes. This division is artificial, usually based upon the plane of the facial nerve. The part of the gland that lies external to the nerve is the superficial lobe; that which lies internal to the plane of the nerve is the deep lobe. Alternatively, this division can also be based upon the plane of the ramus of the mandible. The deep lobe passes through the stylomandibular tunnel and lies laterally to the fat of the prestyloid parapharyngeal space. The stylomandibular tunnel is bounded anteriorly by the ramus of the mandible and posteriorly by the stylomandibular ligament, sternomastoid, and digastric (posterior belly) muscles (Fig. 6.1a).

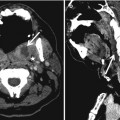

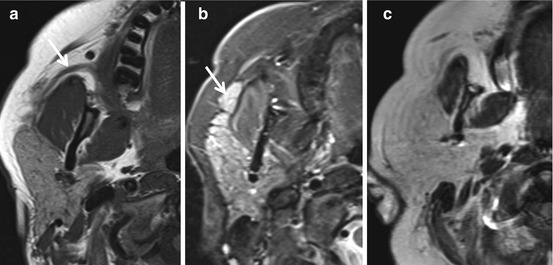

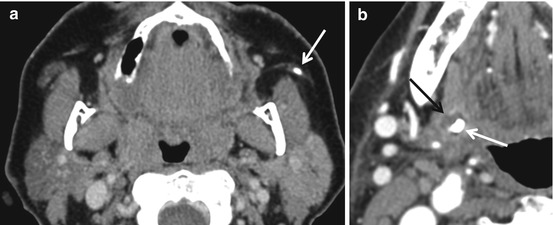

Fig. 6.1

The retromandibular vein (RMV, arrow in a) is consistently seen on cross-sectional imaging. The facial nerve although not directly visible passes lateral to the RMV in an anteroposterior direction. The parotid gland straddles the stylomandibular tunnel (b)

The facial nerve courses lateral to the retromandibular vein. The vein is seen as a constant structure on cross-sectional imaging and is a useful marker for the location of the nerve (Fig. 6.1b).

Accessory parotid tissue may be located along the course of the Stensen’s duct. This should not be mistaken for a mass lesion.

The parotid gland develops before the submandibular and sublingual glands but is the last to encapsulate. This explains the inclusion of small lymph nodes in the parotid space.

The submandibular gland wraps around the free edge of the mylohyoid muscle. The angular facial vein lies dorsal to the gland. A primary submandibular mass displaces the vein posteriorly. When the vein lies anterior to a mass in the submandibular triangle, the mass is not submandibular gland in origin. The key anatomic features of the submandibular and sublingual glands are depicted in (Fig. 6.2).

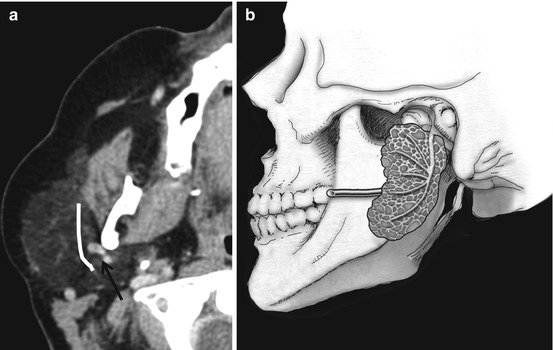

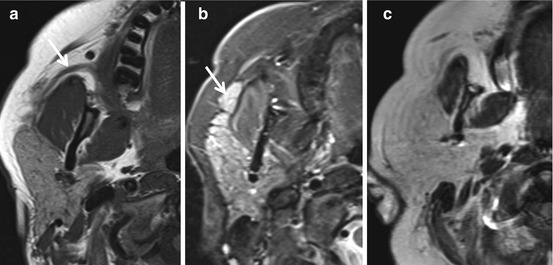

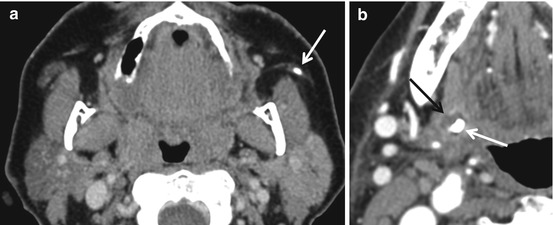

Fig. 6.2

The facial vein lies dorsal to the SMG (arrow in a). The SMG wraps around the posterior edge of the mylohyoid (arrow in b). The mylohyoid sling (black arrow in c) separates the submandibular and sublingual spaces. The sublingual glands are seen as enhancing structures on this coronal MR image (white arrow, c)

Box 6.1 Salivary Gland Anatomy

Location | Ductal drainage | Lymphatic drainage | Secretomotor innervation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Parotid | Parotid space | Stensen’s duct – pierces buccinator to open opposite upper second molar | Intraparotid notes, IIA, IIB | Inferior salivary nucleus → glossopharyngeal N → Jacobson’s N →tympanic plexus → lesser petrosal N → otic ganglion → auriculotemporal N |

Submandibular | Submandibular space | Wharton’s duct – opens adjacent to frenulum linguae in the floor of the mouth | I | Superior salivatory nucleus →f acial N → chorda tympani→lingual N → submandibular ganglion |

Sublingual | Sublingual space | Multiple ducts (Rivinus) open into floor of mouth beside frenulum linguae, some of the smaller ducts may unite to form a larger Bartholin’s duct that joins Wharton’s duct | I | Same as for the submandibular gland |

6.3 Imaging Evaluation

6.3.1 Sialography

This technique is not routinely performed in imaging practice. Cannulation of the submandibular and parotid ducts is achieved with commercially available cannulas (Rabinov). Indications for ductal cannulation include:

1.

Evaluation for lucent calculi

2.

Establishment of diagnoses of inflammatory salivary gland disease, most often Sjögren’s syndrome

3.

Delineation of the fistulae and sinuses related to the parotid glands

A CT may be performed in conjunction with a conventional sialogram.

6.3.2 Cross-Sectional Imaging

CT is often the first line of investigation and is best performed after administration of IV contrast. CT is best used in inflammatory states where identification of calculi and glandular calcification may be of importance and also in the initial evaluation of palpable masses, although MR is superior in the latter. MRI with gadolinium is best used for evaluation of the local extent of salivary gland malignancy. The usage of gadolinium is a must for evaluation of involvement of the facial nerve in cases of suspected parotid malignancy. MR sialography with heavy T2-weighted sequences may be used when the ductal pathology is suspected. MRI with diffusion may aid in the differentiation of benign from malignant masses. Pleomorphic and myoepithelial adenomas especially may demonstrate increased ADC values compared to other lesions.

The appearance of the parotid gland on cross-sectional imaging is largely dependent upon the extent to which its parenchyma is replaced by fat. The gland may be completely fatty in appearance (hypodense on CT, hyperintense on T1-weighted MRI) in patients with hyperlipidemia and sialosis (Fig. 6.3). T1-weighted MRI without contrast is perhaps the most useful sequence for delineation of the margins of a parotid lesion. The salivary glands are easily insonated by ultrasound due to their superficial location. Ultrasound is best used to guide fine-needle aspiration. The role of PET CT is primarily to stage malignant neoplasms.

Fig. 6.3

Normal parotid gland. On the T1-weighted image (a), the gland is of intermediate to high signal. Stensen’s duct (arrow) is also clearly visible. In (b), a T2-weighted image, the gland is hyperintense. A small lobule of accessory parotid tissue (arrow) is seen along Stensen’s duct. In (c), a T1-weighted image, the gland is diffusely hyperintense due to replacement by fat

6.4 Pathology

6.4.1 Congenital Anomalies

Congenital anomalies are in general uncommon. Agenesis of one or more glands and their ducts has been reported. These are more likely to occur in patients with more widespread craniofacial anomalies that may be consequent to abnormal branchial arch development such as in the Treacher Collins and Goldenhar syndromes. Congenital salivary gland cysts are the most common of such anomaly encountered in practice. These may represent any of the following:

First branchial cleft cysts

Lymphoepithelial cysts

Epidermoid cysts

Congenital sialocele

A young patient with a unilocular cystic mass in the parotid gland may be assumed to have a first branchial cleft cyst (Fig. 6.4). The location of these cysts parallels the route of migration of the pinna. The pinna arises from six ectodermal hillocks, three on each side of the first branchial cleft. It migrates from a ventrocaudal location at the angle of the mandible to a dorsocranial location. A first BCC may lie at any location along this course. A type 1 first BCC lies in the preauricular region and may be associated with a tract that runs laterally to the facial nerve and terminates in the wall of the external auditory canal, usually at the junction of its bony and cartilaginous segments. A type 2 first BCC lies near the angle of the mandible and may also be associated with a tract that terminates at the EAC. The relationship of its tract with the facial nerve is however more variable. Demonstration of the tract may not always be possible with imaging. A fistulogram or a heavily T2-weighted fat-suppressed MRI sequence may help.

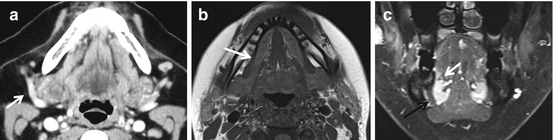

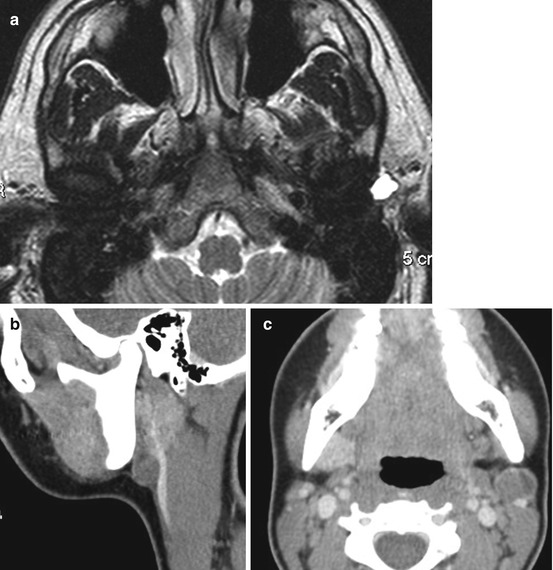

Fig. 6.4

First branchial cleft cysts. A typical type 1 first BCC is shown in (a). The cyst contains clear fluid and is located anterior to the external auditory canal. In the presence of degenerative joint disease, a synovial or ganglion cyst of the TM joint may also present in this location. (b, c) Type 2 first BCC. In a teenager there is faint enhancement of the cyst wall due to recent infection. In an adult, one must always exclude a cystic metastatic lymph node in this location. Mural nodularity or septations are red flags

Congenital cysts are often indistinguishable on imaging. Most of these present as unilocular low-density masses on CT. Occasionally the fluid density of these lesions may be difficult to appreciate on CT due them being isodense to the adjacent glandular parenchyma. Fluid signal intensity is however clearly evident on MRI. Dermoid/epidermoid cysts may contain low-density foci on CT due to the presence of fat and correspondingly demonstrate high T1 signal on MRI.

6.4.2 Infectious and Inflammatory Disorders

A wide variety of bacterial and viral infectious agents may affect the salivary glands. In most cases, there is no specific imaging pattern that enables identification of the offending organism. Bilateral acute parotid enlargement in a young patient may suggest mumps as the etiology. The presence of abscesses, multiple sinuses, and associated parotid and submandibular lymphadenopathy in conjunction with an ill-defined parotid lesion on CT may indicate actinomycosis as the etiology. Identification of bilateral lacrimal gland enlargement in association with multiple parotid masses is suggestive of sarcoidosis. Nonspecific chronic sialadenitis (chronic recurrent sialadenitis) is associated with heterogeneous glandular density and multiple foci of dystrophic calcification.

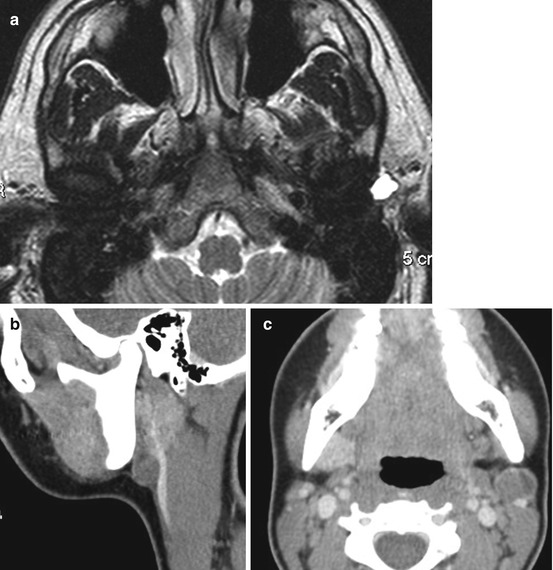

In the acute setting, the role of the radiologist is to determine if an obstructive calculus is present and identify the presence of potentially drainable abscesses (Fig. 6.5). In the case of chronic inflammatory disease, the radiologist may be the first to identify an imaging pattern compatible with a specific disorder such as Sjögren’s syndrome or HIV-associated disease.

Fig. 6.5

Calculi and sialadenitis. Left Stensen’s duct calculus (a) with early parotiditis. The left parotid gland enhances to a greater degree than the right. In (b), a small abscess (black arrow) is seen in the submandibular gland associated with an intraglandular calculus (white arrow)

6.4.2.1 Sjögren’s Syndrome

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree