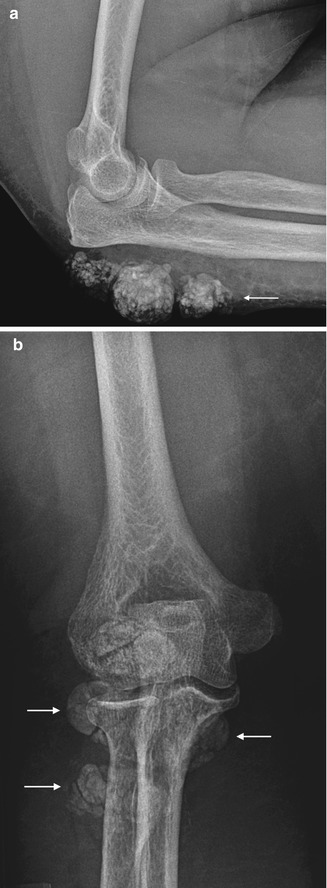

Fig. 16.1

(a) Periarticular soft-tissue calcification in a 16-year-old female with scleroderma. (b) Sheetlike soft-tissue calcification in a different patient with scleroderma

Systemic lupus erythematosus patients may develop periarticular or soft tissue calcification (Fig. 16.2). Calcification can occasionally ulcerate and become secondarily infected.

Fig. 16.2

Periarticular calcification within the volar soft tissues, calcinosis cutis, overlying the distal phalanx thumb in a 27-year-old female patient with SLE

Other connective tissue diseases which contribute to soft tissue calcification include dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Fascial calcifications are almost invariably secondary to the closely related diseases of dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Each of these entities is an uncommon idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. During healing from episodes of myositis, calcifications develop in areas of necrosis (granulomatous changes incorporating calcium) involving the fascial planes and sometimes the subcutaneous tissues. Calcification develops with recurrent myositis. Radiographically, this manifests as numerous small densities in the appendicular skeleton that go on to coalesce and become sheetlike in appearance along ligaments, tendons, and fascial planes and is termed calcinosis universalis (Fig. 16.3).

Fig. 16.3

Dermatomyositis with sheetlike subcutaneous calcification (arrows) over the medial margin distal tibia in a 57-year-old male patient on (a) radiograph and (b) ultrasound demonstrating calcification as linear hyperechoic bands

Crystal Depositional Diseases

Calcium pyrophosphate depositional disease (CPPD), hydroxyapatite depositional disease (HADD), and gout are reviewed in detail in Chap. 8. Calcific tendinosis is most commonly related to the deposition of hydroxyapatite calcific deposits in dystrophic tendons (Fig. 16.4). This is commonly seen around the shoulder, hip, elbow, and wrist. CPPD crystal deposition can occur in hyaline and fibrocartilage. Classically involved areas include the wrist (triangular fibrocartilage), pubic symphysis, knee (hyaline cartilage and meniscus), hip, and shoulder (Fig. 16.5). Calcification can also occur in the rotator cuff muscle secondary to pyrophosphate crystals. Calcified tophi in gout appear as periarticular soft tissue calcification of variable density (Fig. 16.6).

Fig. 16.4

(a) Thickened tendonotic distal Achilles with intratendinous calcification (arrows). (b) 50-year-old female patient with Pellegrini-Stieda lesion (calcification within dystrophic medial collateral ligament posttrauma) and (c) supraspinatus tendon calcification

Fig. 16.5

Chondrocalcinosis with calcification of an extruded medial meniscus (arrow) and calcification articular cartilage (arrowhead)

Fig. 16.6

An 87-year-old male with polyarticular gout demonstrating high attenuation gout tophi on the medial margin first TMTJ and MTPJ (arrows)

Tumoral Calcinosis

Tumoral calcinosis is an uncommon familial entity characterized by the presence of large lobulated masses of calcifications located in the subcutaneous juxta-articular soft tissues and extensor aspect of the extremities (Fig. 16.7). While the majority of individuals are asymptomatic, diminished range of motion is a known complication from large juxta-articular masses as well as neuropathic symptoms due to compression of nearby nerves. Lesions develop in the first two decades, commonly in the locations of known bursae around the hip, elbow, and shoulder. Deposits are often cystic and are composed primarily of calcium hydroxyapatite crystals. Calcium levels are normal, and there is often a mild hyperphosphatemia. Patients may develop associated periosteal reaction, a CPPD-like arthropathy and dental abnormalities. Tumoral calcinosis mimics include the many etiologies of metastatic calcifications, most commonly chronic renal failure.