Solitary Pulmonary Nodules

Todd M. Blodgett, MD

Alex Ryan, MD

Carl Fuhrman, MD

Key Facts

Terminology

Solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN)

Opacity in the lung parenchyma measuring up to 3 cm with no associated mediastinal adenopathy or atelectasis

Imaging Findings

Risk of malignancy highest when nodule has SUV > 2.5 and spiculated morphology

PET/CT superior to CT or PET alone for overall accuracy

Nodules with internal calcifications generally benign

Central calcification is characteristic of benign nodules

Dual-time point imaging may be helpful in differentiating benign from malignant pulmonary nodules

Top Differential Diagnoses

Metastasis

Infection

Granulomatous Disease

Benign Lesions

Pulmonary Infarct

Pathology

Granuloma is the most common entity accounting for SPN

Diagnostic Checklist

Continued CT follow-up in PET-negative SPN

If nodule has features of BAC, a negative PET does not rule out malignancy

Predictive value of stability in size over time of a SPN is only 65%

TERMINOLOGY

Abbreviations and Synonyms

Solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN)

Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC)

Definitions

Opacity in the lung parenchyma measuring up to 3 cm

Usually no associated mediastinal adenopathy or atelectasis

IMAGING FINDINGS

General Features

Best diagnostic clue

High suspicion for malignancy

Any detectable FDG activity higher than background (> mediastinal blood pool) for SPN < 1.5 cm

SUV > 2.5 in any nodule

Spiculated morphology, particularly with a history of smoking

Low suspicion for malignancy

Round nodule with dense calcification and uniform morphology

FDG uptake equal to background activity

Location

No regional pattern for benign nodules

2/3 of primary lung tumors arise in upper lobes

SPN from extrapulmonary primary most often located in outer 1/3 of lower lobes

Size

Definition: Nodule < 3.0 cm < mass

Larger SPN more likely malignant

Over 85% are cancer when larger than 2.0 cm

Growth rate

26% increase in diameter corresponds to a doubling of the nodule’s volume

Time to 26% increase in diameter = one doubling time

Most cancer doubling times: ˜ 30-200 day range

Nodule dimension stability: > 2 years highly suggestive that nodule is benign

Increase in size seen within 30 days suggestive of infection, infarction, lymphoma, fast-growing metastases

Morphology

Benign characteristics

Margin: Well-circumscribed with smooth borders

Density: Fat or water density

Calcification: Common

Cavitation: Wall thickness < 5 mm

Enhancement: Usually minimal

Ground-glass opacity (suggests inflammation)

Air-fluid level (abscess)

Satellite nodules: Common in granulomatous lesions

Malignant characteristics

Margin: Irregular, lobulated, ill-defined with spiculated borders

Density: Soft tissue density

Calcification: 10% demonstrate calcification that is usually peripheral and stippled

Cavitation: Present in 80% of cavitary lung cancers (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma)

BAC may appear entirely as ground-glass opacity

Enhancement: More prominent

Spiculation highly specific for malignancy

Up to 20% of smooth nodules with sharp margins are malignant (e.g., carcinoid)

Air bronchogram: Present in 25-65% of cancers

Pseudocavitation: Common to malignancies such as BAC

Wall thickness > 1.5 cm strongly suggestive of malignancy

Imaging Recommendations

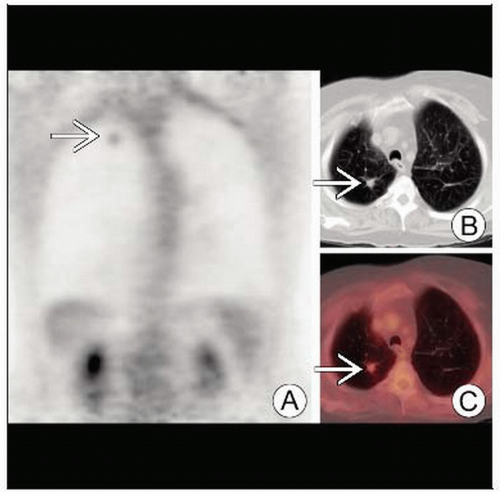

Best imaging tool: PET/CT demonstrates superior accuracy to CT or PET alone

Protocol advice

Dual-time point imaging may be helpful in differentiating benign from malignant pulmonary nodules

Malignant nodules gain intensity between hour 1 and hour 2

Benign nodules decrease in intensity

Radiographic Findings

Chest X-rays (CXR) helpful for determining time course of nodule development

Little change over 2 years or longer is strongly suggestive of a benign process

1-2 SPN detected per 1,000 CXR, routine screening radiographs

CXR has low sensitivity for detection of subcentimeter noncalcified nodules

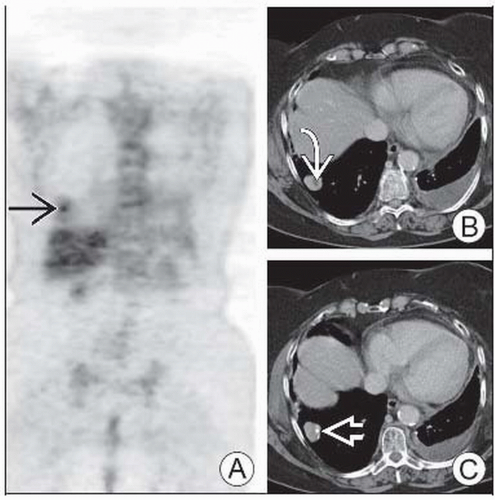

CT Findings

Indications

Accurate localization of nodule (intra-/extrapulmonary)

Detection of additional unsuspected nodules

Characterization of margin, density, and calcification patterns

Assessment of extrapulmonary involvement (lymph nodes, pleura, chest wall, liver, adrenals, etc.)

Malignant morphology

CT may misclassify 25-40% of nodules as benign based on morphologic characteristics

BAC and lymphoma, for example, often appear benign

Coarse spiculation and bronchovascular bundle thickening around tumor

More common in presence of vessel invasion &/or lymph node metastasis

Heterogeneous internal composition

Hazy or indistinct margins

Peripheral spiculation with halo

Pleural retraction adjacent to tumor

Necrosis

Extension to bronchi or pulmonary veins

SPN calcification characteristics

Malignant

Generally not calcified

Nodules with eccentric calcification cannot be classified as benign

Bone cancer, soft tissue sarcoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma metastases may calcify

1/3 of carcinoid tumors calcify

Colon and ovarian metastases may show psammomatous calcification

Internal hemorrhage may simulate calcification (melanoma and choriocarcinoma)

Benign

Central, laminated, popcorn, diffuse

Diffuse calcifications > 300 HU through nodule

> 1/2 granulomas are calcified

1/3 of hamartomas have popcorn calcification

Ground-glass opacity (GGO)

GGO nodules are lower density than solid nodules and do not obscure lung parenchyma

20% of lung nodules demonstrate this density

34% of these are malignant

More difficult to distinguish malignant from benign disease based on morphology

Much higher incidence of malignancy among ground-glass and mixed opacity nodules

Bronchoalveolar carcinoma often demonstrates this density

Also adenocarcinoma with BAC features

Adenocarcinoma > 2 cm with > 50% GGO has low risk of lymph node metastasis and vessel invasion

Enhancement

Malignant nodules often hypervascular and highly enhancing

Generally, > 25 HU = malignant, and < 15 HU = benign

Insensitive for subcentimeter, cavitary, or necrotic nodules

Fat

Malignant: Liposarcoma, renal cell carcinoma metastases (uncommon)

Benign: Hamartoma, lipoid pneumonia

Air bronchograms

Caused by small airway distortion

More typical of malignant than benign nodules

Seen in 30% of malignant nodules and 6% of benign nodules

As much as 55% of BAC shows bubble-like lucencies = pseudocavitation

Nuclear Medicine Findings

PET

Significant overlap in FDG activity between benign and malignant nodules

SUV > 2.5 has sensitivity/specificity 90-100%, 69-95% for detection of malignancy

Detection depends largely on size

Lower resolution limit 6-8 mm

Partial volume averaging of small nodules can produce falsely low SUV

Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma has multifocal form that is often detected with FDG PET

Overall, BAC tends to have lower FDG uptake than other pulmonary malignancies

False positives

Focal hypermetabolic uptake unrelated to malignancy

Most common include infection, inflammatory reaction, granulomata, hamartoma

False negatives

Malignant subcentimeter nodules may not be detected on FDG PET

Hypometabolic tumors: BAC, carcinoid

Temporary decrease in FDG uptake of active lesions post-therapy (“stunned tumor”)

Ground-glass nodules often false negative due to size and association with BAC

PET provides prognostic information for malignant nodules

May be more accurate than pathology in predicting recurrence-free survival

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree