, Mark J. Jameson2, Max Wintermark3, Prashant Raghavan4 and Sugoto Mukherjee5

(1)

Clinical Instructor, Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, Division of Neuroradiology, Charlottesville, VA, USA

(2)

Division of Head and Neck Surgical Oncology, Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

(3)

Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

(4)

Division of Neuroradiology, Department of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

(5)

Division of Neuroradiology, Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

Abstract

This chapter describes an anatomic approach to pathology of the neck. A solid understanding of the anatomic boundaries of the spaces of the neck allows one to elucidate a focused differential diagnosis and evaluate for specific invasion or extension; these insights help the surgeon determine optimal operative management. This chapter will focus on the parapharyngeal, masticator, carotid, and posterior spaces. The parotid, submandibular/sublingual, and pharyngeal mucosal spaces are discussed in detail in other chapters.

1.1 Introduction

This chapter describes an anatomic approach to pathology of the neck. A solid understanding of the anatomic boundaries of the spaces of the neck allows one to elucidate a focused differential diagnosis and evaluate for specific invasion or extension; these insights help the surgeon determine optimal operative management. This chapter will focus on the parapharyngeal, masticator, carotid, and posterior spaces. The parotid, submandibular/sublingual, and pharyngeal mucosal spaces are discussed in detail in other chapters.

Accurate interpretation of head and neck imaging requires an understanding of fascial layers, which cannot be precisely delineated with imaging; in practice, key anatomic landmarks define these fascial layers. The superficial cervical fascia (SCF) envelops fat, loose connective tissue, the platysma, and the external jugular veins. The deep cervical fascia (DCF) is further divided into superficial (SLDCF), middle (MLDCF), and deep (DLDCF) layers that form the boundaries of the spaces of the suprahyoid neck described in detail below.

1.2 Imaging Evaluation

Conventional radiography has largely been replaced by cross-sectional imaging in the evaluation of the soft tissues of the neck.

In the appropriate setting, ultrasound is a valuable tool in evaluation of the neck. Superficial lesions can typically be adequately imaged and described in the hands of an experienced sonographer. Ultrasound provides the added benefit of providing real-time image guidance for biopsy or drainage. However, ultrasound is inadequate in the evaluation of the deeper spaces of the neck.

CT is the mainstay of evaluation of neck lesions. Intravenous contrast is recommended, as lesions often cannot be delineated from adjacent normal tissues without it. Dental amalgam can sometimes present a challenge in evaluation of masses in the pharyngeal mucosal, sublingual, submandibular, and masticator spaces; this can often be overcome by angling the gantry at 15–25° (so-called butterfly cuts) and reimaging through the oral cavity.

MRI is a very useful tool for evaluating head and neck masses. When used with a dedicated neck coil, the deep and superficial structures of the neck can be clearly identified. Intravenous contrast is recommended to help characterize masses and enable accurate detection of tumor spread. When evaluating for spread of malignancy, it is vital to obtain precontrast T1-weighted images without fat suppression. The bright signal intensity of fat on this sequence provides a useful background against which the soft tissue intensity of tumor can be detected. The addition of fat suppression to post-contrast sequences facilitates better delineation of the enhancing tumor margins. The main disadvantages of neck MRI are the artifacts produced by dental hardware or amalgam and the length of time the patient may have to remain in the scanner (often 30–60 min), which frequently results in motion artifact.

1.2.1 Parapharyngeal Space

1.2.1.1 Anatomy

In clinical otolaryngology, the term “parapharyngeal space” has been used inclusively to refer to what is described above as the PPS and the carotid space. In this nomenclature scheme, the two distinct compartments were identified as the prestyloid and poststyloid compartments, respectively. For the purposes of consistency in this discussion, the terms PPS (prestyloid compartment) and carotid space (poststyloid compartment) will be used.

The parapharyngeal space (PPS) can be thought of as an inverted pyramid extending from the inferior surface of the petrous bone to the lesser horn of the hyoid bone. Its central location in the deep spaces of the suprahyoid neck results in a complex fascial anatomy (Fig. 1.1). The PPS extends medially to the aerodigestive tract; the visceral fascia is its medial border. The visceral fascia (deepest layer of MLDCF) adheres to the visceral structures of the neck, including the pharynx, larynx, esophagus, trachea, thyroid gland, and parathyroid glands. Anteriorly and laterally, the PPS abuts the masticator and parotid spaces, respectively. The SLDCF splits to envelop these spaces. As such, the anterior and lateral walls of the parapharyngeal space are leaflets of the SLDCF. The DLDCF of the carotid space and that of the lateral margin of the retropharyngeal space demarcate the posterior margin of the PPS. Some texts indicate that there is no fascial separation between the PPS and the submandibular space, allowing direct spread of infection or tumor between the two spaces.

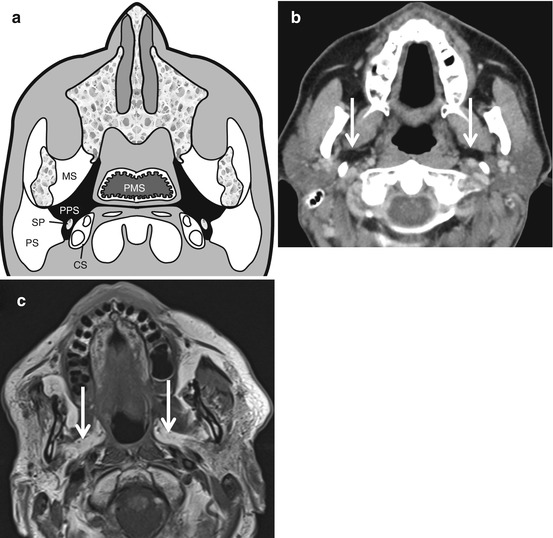

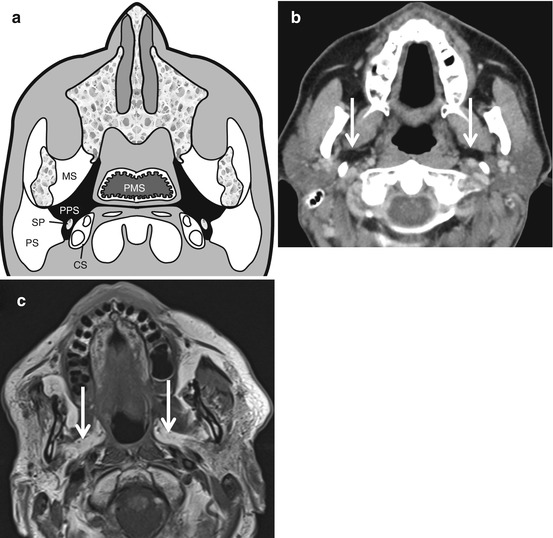

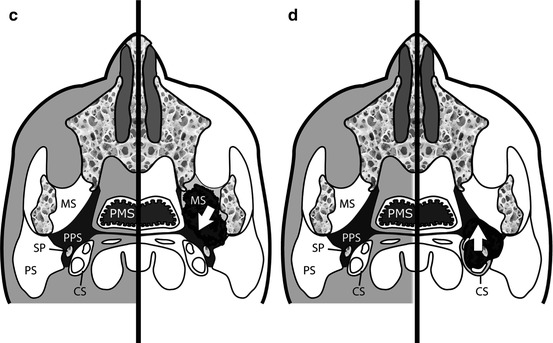

Fig. 1.1

Neck spaces. Axial graphic (a), CT (b), and T1-weighted MR (c) images show the normal anatomy of the parapharyngeal space (PPS). This space predominantly contains fat and can be easily identified (arrows in b and c) on both CT (hypodense on CT) and MR (bright on T1-weighted sequences) images. The central location of this space is the reason for its displacement in lesions arising from the adjacent masticator space (MS), parotid space (PS), carotid space (CS), and the pharyngeal mucosal space (PMS). The styloid process (SP) is along the posterior aspect of the parapharyngeal space. Note that, infrequently, lesions can arise primarily from within the parapharyngeal space and can be completely surrounded by adjacent fat

The PPS is predominantly comprised of fat, making it readily identifiable on CT and MRI (Fig. 1.1). Also present are small branches of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (V3), the ascending pharyngeal artery, the internal maxillary artery, lymph nodes, and minor salivary rests (Box 1.1).

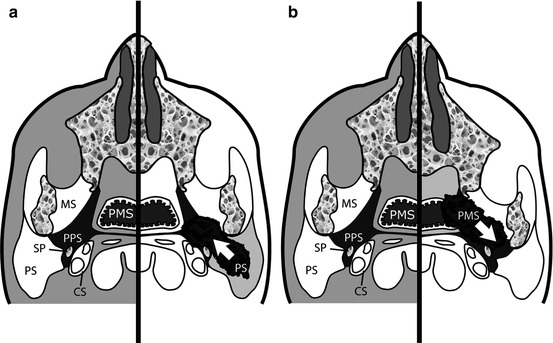

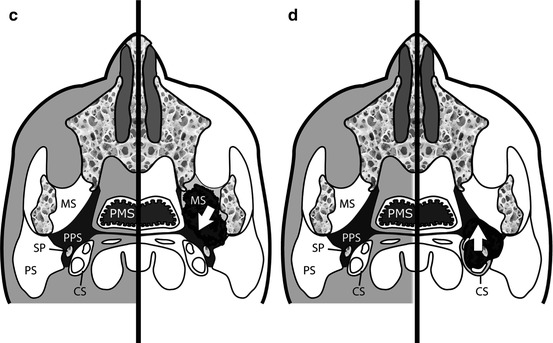

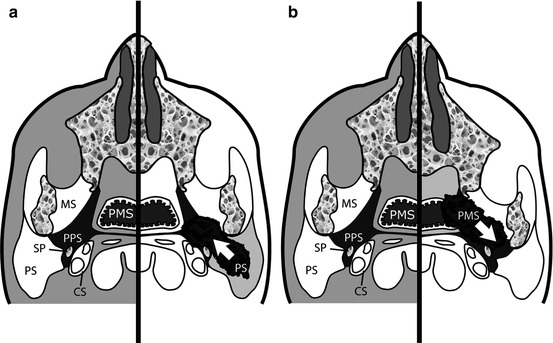

When a mass arises in an adjacent space, the fat in the parapharyngeal space can become deformed and displaced. Observation of the direction in which the mass displaces the parapharyngeal fat can help determine the origin of the mass (Fig. 1.2). Box 1.2 summarizes the expected effect of adjacent masses on the parapharyngeal space.

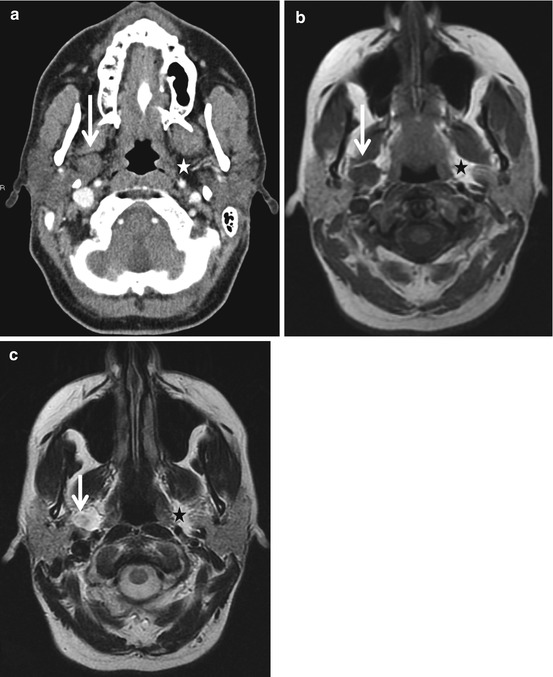

Fig. 1.2

Displacement of fat in the parapharyngeal space (PPS) by lesions in adjacent spaces which are masticator space (MS), parotid space (PS), carotid space (CS), and the pharyngeal mucosal space (PMS). The styloid process (SP) is along the posterior aspect of the parapharyngeal space. These include anteromedial displacement (a) by a lesion arising from the deep lobe of the parotid gland from PS (such as a pleomorphic adenoma), posterolateral displacement (b) of the fat by a pharyngeal mucosal space (PMS) lesion (such as a nasopharyngeal carcinoma), posteromedial displacement (c) from a masticator space (MS) lesion, or anterior displacement (d) from a lesion arising from the carotid space (CS) lesion (nerve sheath tumors or paragangliomas)

Box 1.1. Spaces of the Neck: Contents and Lesions

Space | Contents | Lesions |

|---|---|---|

Parapharyngeal space | Fat | Benign mixed tumors – either from ectopic rests in parapharyngeal space or from deep lobe of the parotid |

Ectopic rests of salivary glands | Lipoma | |

Branches of mandibular division of trigeminal nerve | Schwannomas | |

Internal maxillary artery | Cellulitis/abscess | |

Ascending pharyngeal artery | ||

Pharyngeal venous plexus | ||

aMasticator space | Internal maxillary artery and its branches | Odontogenic abscess |

Mandibular nerve and its branches | Sarcomas | |

Ramus/body of mandible | Neurogenic tumors | |

Muscles of mastication | Vascular malformations | |

Perineural spread of carcinomas | ||

Secondary involvement from jaw, skull base, and pharyngeal mucosal space lesions | ||

Carotid space | Internal carotid artery | Internal carotid artery aneurysm/dissection |

Internal jugular vein | Internal jugular vein thrombosis | |

Cranial nerves IX–XII | Schwannomas/neurofibromas of the cranial nerves IX–XII and sympathetic chain | |

Cervical sympathetic chain | Paragangliomas – carotid body tumors, glomus vagale | |

Glomus bodies | Inferior extension of lesions from jugular foramen (schwannomas/neurofibromas/meningiomas/glomus jugulare) | |

Jugular chain nodes | Metastatic adenopathy | |

aParotid space | Parotid gland | Salivary gland tumors |

Intraparotid lymph nodes | Metastatic tumors | |

Facial nerve and branches | Lymphomas | |

Internal carotid artery | Perineural extension through facial nerve | |

Retromandibular vein | Cystic lesions | |

aPharyngeal mucosal space | Squamous epithelial mucosa | Squamous cell cancers incl. nasopharyngeal carcinomas |

Lymphoid and tonsillar tissue | Lymphomas | |

Minor salivary glands | Minor salivary gland tumors | |

aVisceral space | Larynx and hypopharynx | Squamous cell cancers |

Thyroid and parathyroid | Thyroid and parathyroid tumors | |

Esophagus | Vascular malformations | |

Thyroglossal and branchial cysts | ||

Benign mesenchymal and neurogenic tumors | ||

Dermoids/epidermoids | ||

Retropharyngeal space | Fat | Metastatic adenopathy |

Medial and lateral retropharyngeal nodes | Lymphoma | |

Perivertebral space | Prevertebral/paravertebral muscles | Abscess/osteomyelitis |

Cervical vertebra | Osseous metastasis | |

Phrenic and cervical nerves | Schwannomas/neurofibromas |

Box 1.2. Lesion Localization in Suprahyoid Neck

Lesion location | Displacement |

|---|---|

Pharyngeal mucosal space | Posterolateral displacement of parapharyngeal fat |

Posterior displacement of styloid process | |

Masticator space | Posteromedial displacement of parapharyngeal fat |

Posterior displacement of styloid process | |

Carotid space | Anterior displacement of parapharyngeal fat and styloid process |

Parotid space | Anteromedial displacement of parapharyngeal fat |

Retropharyngeal | Anterolateral displacement of parapharyngeal fat |

Anterior displacement of styloid process |

1.2.1.2 Pathology

Primary masses of the PPS are rare. More commonly, tumors arise from the deep lobe of the parotid gland or from an adjacent space and extend into the PPS. The most common masses involving the parapharyngeal and the adjacent spaces are listed in Box 1.1.

Of the primary PPS neoplasms, benign tumors account for 80 %. The most common is a pleomorphic adenoma (benign mixed tumor) arising from a minor salivary gland rest. As shown in Fig. 1.3, pleomorphic adenomas are typically well marginated and bright on T2 with heterogeneous enhancement. It is important to distinguish a pleomorphic adenoma arising from a minor salivary gland rest in the PPS from those arising from the deep lobe of parotid gland as this has significant surgical implications: masses centered in the PPS should be fully encompassed by PPS fat. The presence of small branches from V3 gives rise to neurogenic tumors (schwannomas and neurofibromas), which tend to be well defined, but are typically less bright on T2 than pleomorphic adenomas; they may, however, be indistinguishable. This distinction is not vital, as long as the radiologist is confidently able to place the mass in the PPS. Lipomas are rare encapsulated fatty tumors that follow fat signal and density on all MR sequences and CT, respectively. Malignant neoplasms, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma are uncommon. As in other spaces, malignant neoplasms are infiltrative and demonstrate avid, though not always uniform, enhancement.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

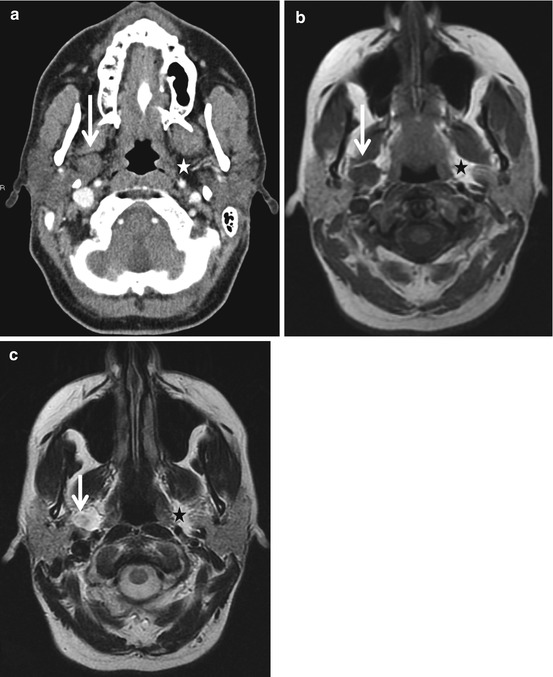

Fig. 1.3

Pleomorphic adenoma. Axial CT (a) and T1- and T2-weighted MR images (b and c

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree