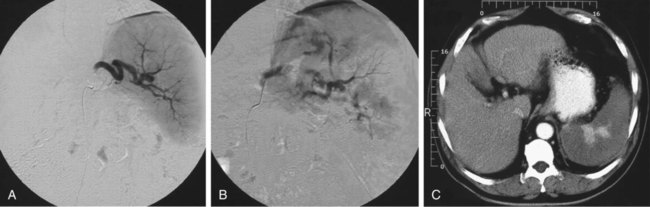

Hypersplenism due to portal hypertension is certainly the primary indication for embolization of arterial splenic tissue.1,2 Causes of hypersplenism vary. Most patients have alcoholic or postnecrotic liver cirrhosis, with a platelet count of less than 60,000/mm3 and at least one major episode of bleeding from ruptured gastroesophageal varices. Embolization of the spleen has the advantage of retaining the organ in place, and a distal splenorenal shunt is still possible after correction of the anemia and thrombocytopenia. Splenic embolization is also indicated in patients being maintained on hemodialysis who have pancytopenia and splenomegaly, and in renal transplant patients in whom intolerance to immunosuppressive medications after renal transplantation had to be corrected.3 Thalassemia is also responsible for progressive hypersplenism, which requires an increase in the number of blood transfusions.4,5 Partial splenic embolization is a valid alternative to splenectomy in this group of patients, in whom the risk for infections and lethal complications is particularly high after splenectomy. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura may also be corrected by splenic embolization.6,7 The procedure is well tolerated in these patients because the spleen is of normal volume or only moderately enlarged. The physiopathologic mechanism of correction of thrombocytopenia has not been completely elucidated. Infarction of splenic tissue probably decreases sequestration of platelets in the spleen and reduces intrasplenic production of autoantibodies directed against platelets. Splenic embolization has been used in a variety of other pathologic conditions, such as splenic lymphoma, chronic lymphatic leukemia, myeloid leukemia, myelofibrosis, hairy cell leukemia, polycythemia vera, hereditary spherocytosis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, idiopathic hypersplenism, and Felty syndrome, as well as in patients with hypersplenism and cytopenia induced by anticancer chemotherapy.8–11 Preoperative partial splenic embolization has also been advocated before laparoscopic splenectomy,12,13 in a tumorous spleen when correction of hypersplenism and reduction of tumor mass are expected, and in patients with hypersplenism, those at high operative risk, and those who refuse blood transfusion (Jehovah’s Witnesses).14 For anatomy of the celiac trunk and splenic vessels, refer to Chapter 52. • Intramuscular injections of 1,000,000 units of penicillin G with 3 mg/kg of gentamicin for 5 days after embolization • A dosage of 0.5 g of cephalothin administered as four injections per day for 15 days after embolization • Tobramycin (1 mg/kg) and oxacillin (1 g) intravenously 30 minutes before the procedure • In children, gentamicin (10 mg/kg/day) and cefoxitin sodium (100 mg/kg/day) intravenously for 5 days or longer • A 14-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine administered a few days before embolization The extent of infarction has to be assessed during the procedure. When a significant reduction in flow of contrast medium is observed in the splenic artery, embolization is stopped. At that moment, the extent of infarction generally corresponds to 70% to 80% of the splenic volume (Fig. 72-1). Angiography can be performed during the procedure to assess the progression and extent of embolization. Angiographic catheter exchange is avoided during the procedure to prevent septic complications.

Splenic Embolization in Nontraumatized Patients

Indications

Technique

Anatomy and Approach

Technical Aspects

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

Embolization Technique and Material

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree