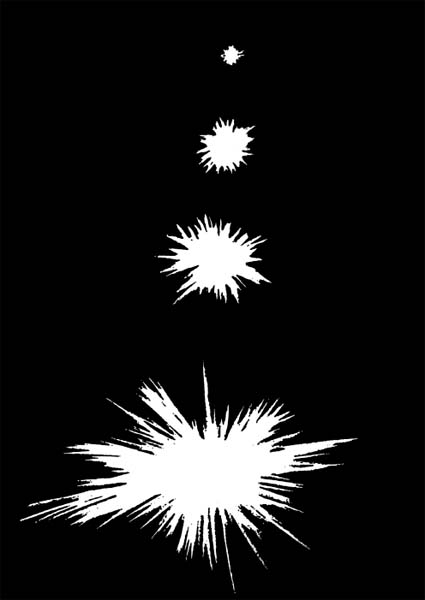

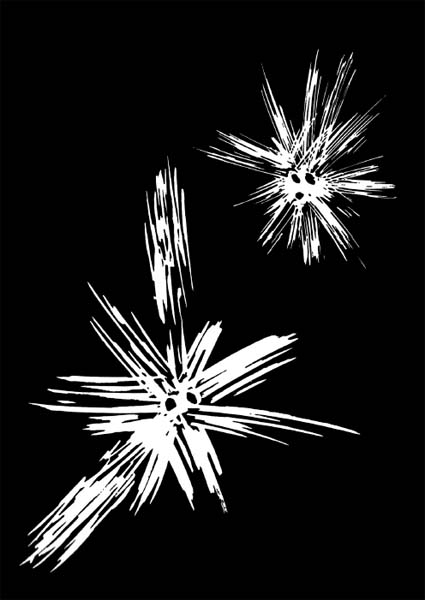

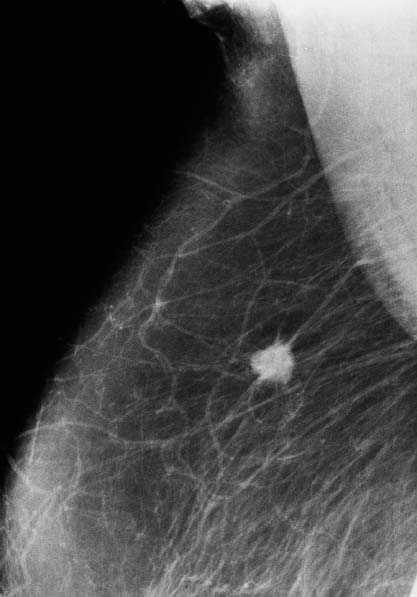

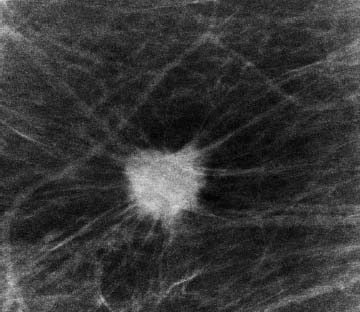

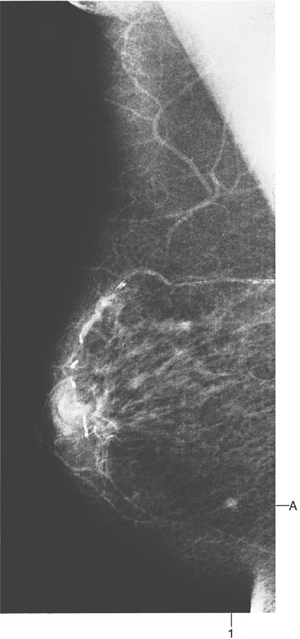

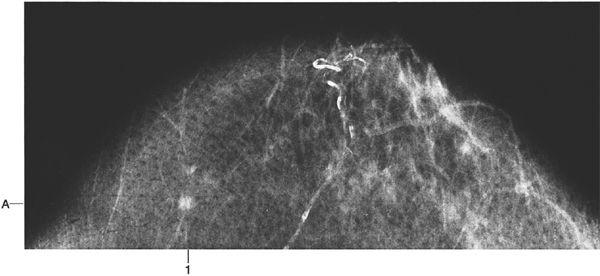

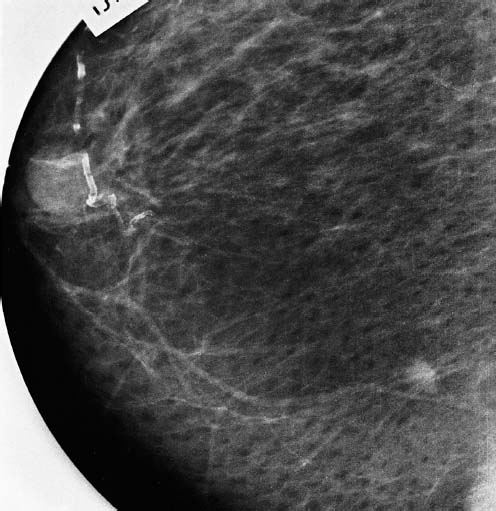

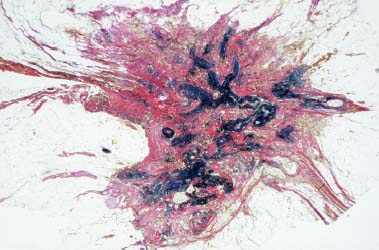

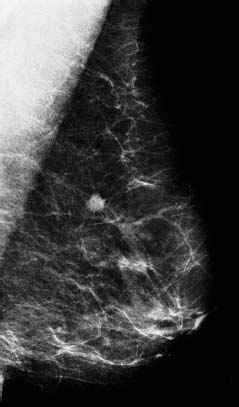

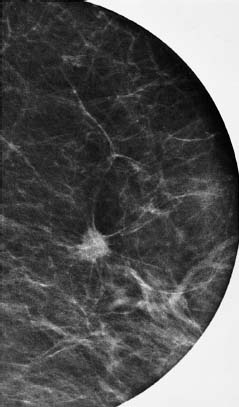

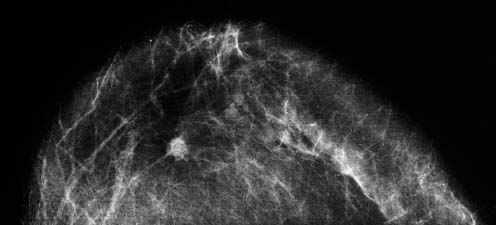

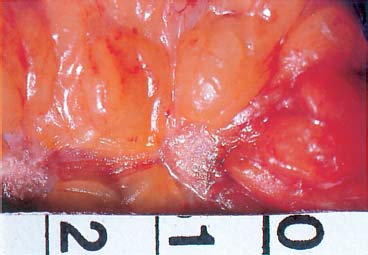

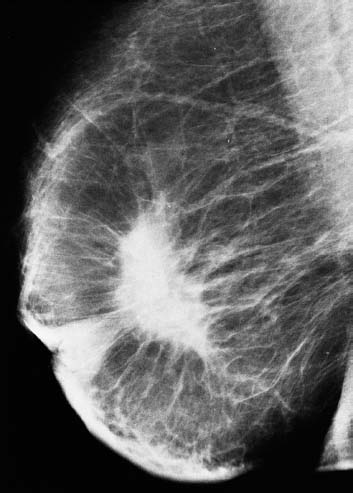

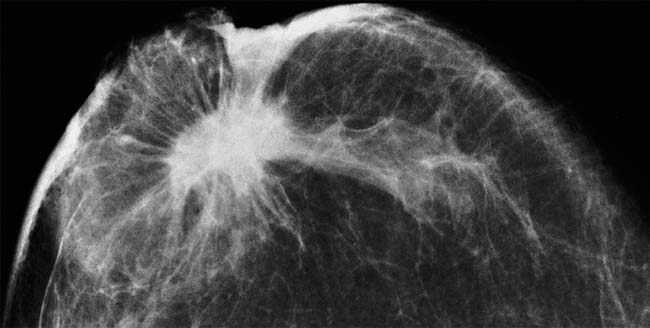

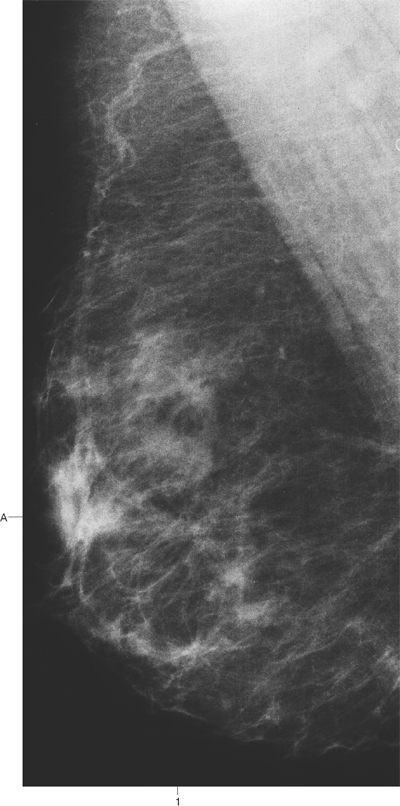

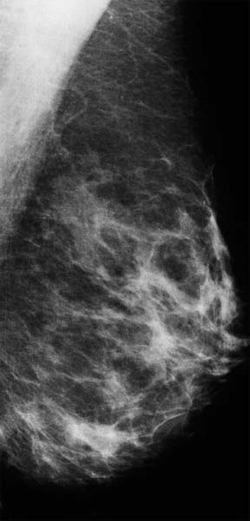

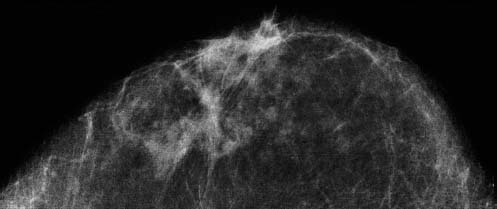

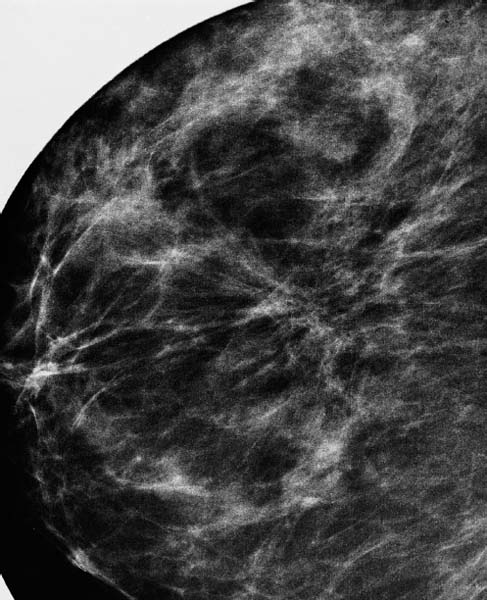

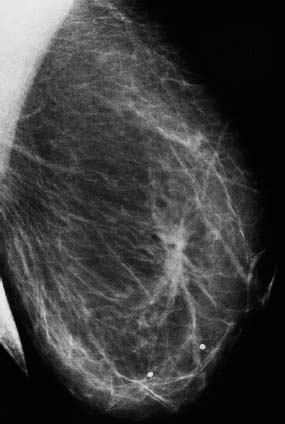

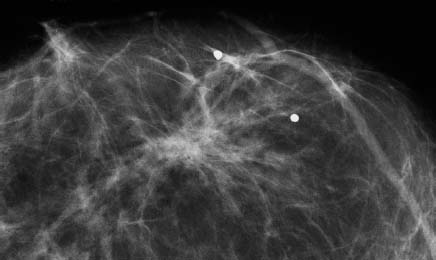

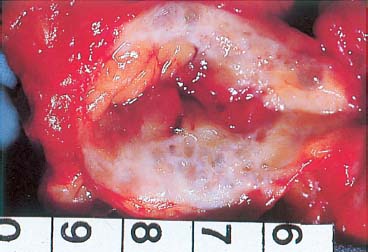

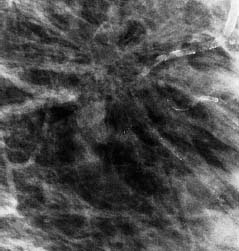

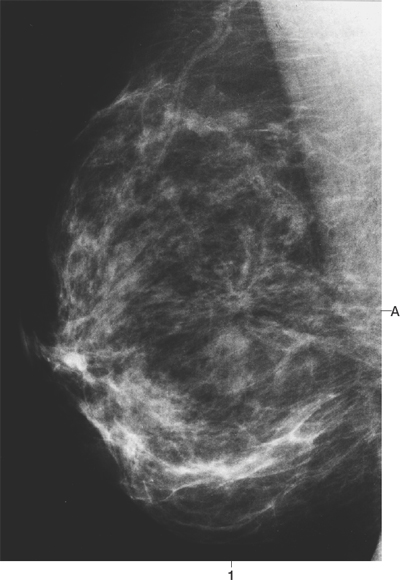

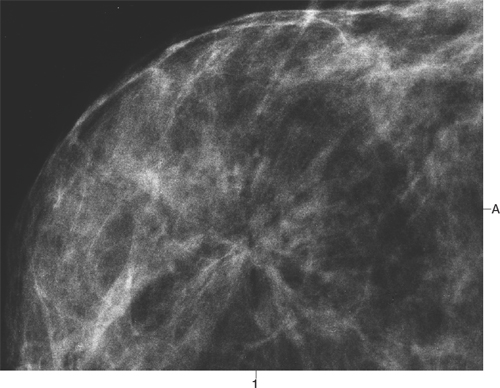

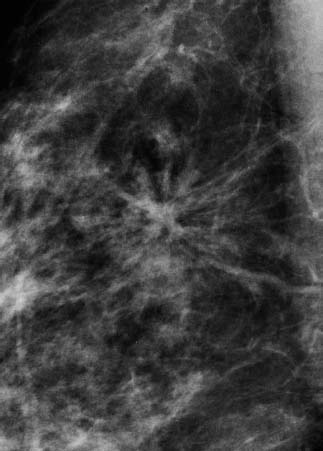

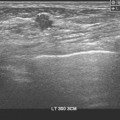

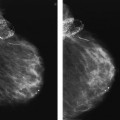

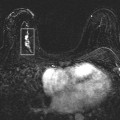

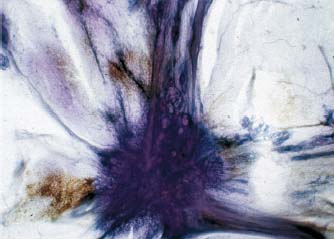

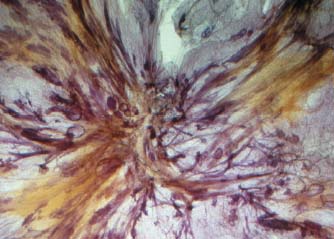

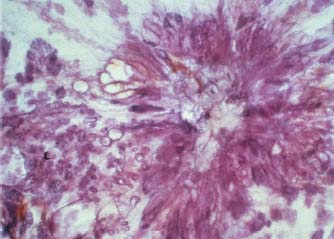

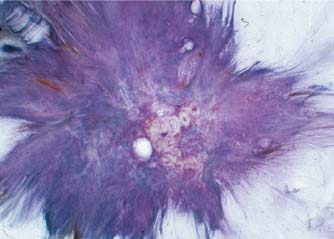

V Stellate/Spiculated Lesions and Architectural Distortion Subgross (3D) histology images Stellate invasive ductal carcinoma A radial scar An additional radial scar An additional invasive ductal carcinoma Malignant Diseases • Invasive ductal carcinoma NOS (not otherwise specified) • Invasive lobular carcinoma • Neoductgenesis Benign Diseases • Radial scar • Traumatic fat necrosis When viewing stellate/spiculated lesions and architectural distortion, proper analysis of both the central portion and the radiating structure itself will lead to the correct diagnosis. Spot compression microfocus magnification views are of great value in evaluating these mammographic signs. Analysis of the central portion may show either a distinct mass or oval/circular radiolucent areas. Each is associated with its own characteristic surrounding radiating structure, resulting in one of two mammographic images that are diagnostic: • “white star” (Fig. XXI): sharp, dense, fine lines of variable length radiating in all directions from a distinct central tumor mass. This is the typical picture of invasive ductal and tubular carcinoma (Cases 57, 58, 59, 60, 65, 70, 71, 72, 73, 85). The larger the central tumor mass, the longer the spicules. These are composed of dense collagen, and are seen on the mammogram as high-density radiopaque linear structures. They occasionally contain in situ or invasive carcinoma, indistinguishable from those containing only collagen. The spicules may reach the skin or muscle, causing retraction and localized skin thickening, which is often present in large or superficial invasive ductal carcinomas (Case 60). Skin changes may also be present in traumatic fat necrosis, especially postoperatively (Cases 68, 69). Malignant-type calcifications are commonly associated with a white star • “black star” (Fig. XXII): a radiating structure consisting of linear densities interspersed with linear radiolucencies; this picture, combined with the circular or oval radiolucent areas at the center, dominates the mammographic image (“black star”) (Case 81). These are the characteristic features of a radial scar (sclerosing duct proliferation/hyperplasia), which consists of proliferating ducts with periductal elastosis, arranged in a radiating fashion (Cases 61, 62, 63, 64, 66, 67, 81, 82, 83). Radial scars vary in appearance from one mammographic projection to the other. Each view may thus give a somewhat different picture. A similar mammographic appearance can occasionally be seen in traumatic fat necrosis (Case 68). This mammographic image of a black star is unlike the radiating structure of an invasive cancer. A radial scar is never associated with skin thickening or retraction and there is a striking difference between the distinct mammographic findings and the nearly complete absence of a palpable lesion, no matter how large or superficial it may be. Ultrasound examination assists in the differential diagnosis because the center of a radial scar shows cystic dilatation of the proliferating ducts, unlike the typical dense, acoustic shadowing of an invasive carcinoma. Fig. XXI Diagrammatic illustration of invasive ductal carcinoma: the larger the central tumor mass, the longer the spicules. The mammographic appearance of the small, usually nonpalpable invasive ductal and tubular carcinomas may differ from the typical appearance of a white star: • the earliest detectable phase of an invasive carcinoma may present as a nonspecific asymmetric density lacking the typical radiating structure of a tumor, but it also lacks the terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs) and other building blocks of the normal breast parenchyma. When this nonspecific asymmetric density is found in any of the four “forbidden areas” described in Chapter II, it raises the suspicion of malignancy and requires further workup (Cases 74, 76, 78). Higher-resolution magnification mammography images may reveal a small central tumor mass not seen in the initial mammographic images, and breast ultrasound can be very effective in confirming the malignant nature of the asymmetric density • the asymmetric density may consist of a lace-like, fine reticular structure which causes parenchymal distortion. This may be the only change leading to detection (Case 75). Architectural distortion without a central tumor mass may also be caused by the following diseases: • invasive lobular carcinoma, classic type. Due to the absence of E-cadherin, the cancer cells spread along the existing breast structures, such as fibrous strands and ducts, which will eventually cause a fine, web-like/reticular pattern, distorting the normal breast structure (Case 83) • neoductgenesis. Certain subtypes of breast cancer are characterized by formation of new, duct-like structures, resulting in an unnaturally high concentration of these abnormal, tumor-filled ducts within a limited volume. The mammographic image shows an asymmetric density with architectural distortion, with or without associated malignant-type calcifications (Case 84). When present, the most characteristic calcifications in these cases are the so-called casting type—long, branching, fragmented, or dotted calcifications (Chapter VI)1 • radial scar (sclerosing duct hyperplasia). This benign, rarely palpable lesion may be mistakenly diagnosed as carcinoma; conversely, invasive lobular carcinoma may occasionally give the mammographic impression of a radial scar. Mammography screening has brought attention to this lesion. A prevalence of 0.9 per 1000 was observed in our prevalent screening material. The occurrence of this cancer-imitating lesion makes it an important practical problem, since about one-third of these lesions are associated with cancer in situ or tubular carcinoma.2 Furthermore, the exact nature of this lesion is a subject of some controversy among pathologists and it has been given many different names3–10 • traumatic fat necrosis. Fat necrosis following trauma, including surgery, can result in at least two basic types of mammographic image—a circular/oval lesion (hematoma developing into an oil cyst) and a stellate lesion. Calcification may be associated with either of these (Chapter VI). Relevant patient history contributes to the diagnosis. The presence of ecchymosis is useful. The characteristic mammographic appearance, when the traumatic fat necrosis results in a stellate lesion, is as follows (Cases 66, 68, 84): —center of the lesion: there is seldom a distinct mass unless the necrosis has resulted from secondary healing. Typically, translucent areas corresponding to small oil cysts are seen in the central portion. The older the lesion, the less solid the center (Cases 68, 84) —radiating structure: varies with the projection, particularly in spot compression views. Spicules are fine and of low density —localized skin thickening and retraction may be present (Cases 68, 69, 84). Note: The combination of patient history, physical examination and mammographic findings is necessary to arrive at the correct diagnosis. Although the definitive diagnosis of architectural distortion on the mammogram requires histologic examination, the preoperative differentiation between malignant stellate lesions and radial scars based on mammographic signs will have a significant influence upon the management of these lesions. In stellate lesions suspicious for malignancy (“white star”), preoperative needle biopsy should establish the diagnosis and will greatly facilitate the treatment planning (one-stage operation, sentinel node/axillary dissection, etc.). On the contrary, the use of preoperative needle biopsy of radial scars (“black star”) carries a considerable risk of overdiagnosis/underdiagnosis and should be avoided. Complete surgical removal and thorough histological examination should be carried out when a radial scar is suspected. The diagnosis of traumatic fat necrosis can be established by the patient’s history, characteristic mammographic findings, and, when necessary, by large-core needle biopsy. This case is meant to demonstrate the characteristics of a typical malignant stellate tumor. It is recommended that radiologists refer to this case while analyzing other stellate lesions. The presence of a central tumor mass with associated spicules is typical of malignant stellate tumors. The spicules are dense and sharp, radiating from the tumor surface, usually not bunched together. When they extend to the skin or areolar region they cause retraction and local thickening. The larger the tumor mass, the longer the spicules (see Fig. XXI). A 73-year-old asymptomatic woman. First screening study. Physical Examination No palpable tumor. Mammography Fig. 58 a: Right breast, mediolateral oblique (MLO) projection. A small tumor shadow is seen at coordinate A1. Fig. 58 b: Right breast, craniocaudal (CC) projection. The tumor is seen at coordinate A1. There are no associated calcifications. Fig. 58 c: Magnification view, MLO projection. Analysis Form: small tumor mass surrounded by spicules Size: 4 × 4 mm Conclusion Mammographically malignant tumor. Histology Infiltrating ductal carcinoma, size 4 × 4 mm. No axillary metastases. Fig. 58 d: Specimen photograph. Fig. 58 e: Overview of the tumor with staining for elastic fibers (12.5 ×). Follow-up The woman died 1 year and 11 months later from pulmonary embolism, aged 75 years. There was no evidence of breast cancer at the time of death. A 63-year-old asymptomatic woman. First screening examination. Physical Examination No palpable tumor. Mammography Fig. 59 a: Left breast, MLO projection. Fig. 59 b: Magnification view in the MLO projection. Fig. 59 c: Left breast, CC projection. A stellate tumor is seen in the upper inner quadrant, 7 cm from the nipple. There are no associated calcifications. Conclusion This tumor has the typical mammographic appearance of a malignant stellate breast tumor: solid center, radiating spicules (“white star”). Histology Invasive ductal carcinoma. Maximum diameter 7 mm. No lymph node metastases. Fig. 59 d: Specimen photograph. Follow-up The woman died 8 years and 5 months later from colon cancer. At the time of death, there was no evidence of metastatic breast cancer. An 89-year-old woman with a 1-year history of a slowly growing tumor in the right breast. Physical Examination A large, obviously malignant tumor in the right breast. Mammography Fig. 60 a, b: Right breast, MLO and CC projections. Centrally located, large (5 cm diameter) stellate tumor. The nipple and areola are retracted. The skin is thickened and retracted over the lower and outer portions of the breast. Comment This is an illustrative example of an advanced stellate malignant breast tumor with a large central tumor mass and radiating spicules that retract the areola and skin. Histology Infiltrating ductal carcinoma. The tumor infiltrates the lymph vessels. Follow-up The patient died 1 year and 6 months later of metastatic breast carcinoma. A 61-year-old asymptomatic woman. First screening study. Physical Examination No palpable tumor, no history of trauma. Mammography Fig. 61 a, b: Right (a) and left (b) breasts, MLO projections. Compare the lower halves of the right and left breasts. In the lower half of the right breast there is architectural distortion centered at coordinate A1. Fig. 61 c: Right breast, CC projection. Fig. 61 d: Right breast, microfocus magnification view, MLO projection. Compare Fig. 61 a with Fig. 61c, d. Observe how the lesion has a different appearance in each projection. Form: radiating structure with no central tumor mass; the magnification view in particular shows the small radiolucencies at the center of the lesion; the radiating structure is formed by long slightly curved linear densities interspersed with radiolucent adipose tissue Size: the lesion occupies much of the lower outer breast quadrant Conclusion This mammographic appearance is typical of a radial scar. The diagnosis is supported by the lack of palpatory findings. No further diagnostic procedures are indicated. In fact, needle biopsy is contraindicated (see p. 104). The next step should be open surgical biopsy followed by careful histologic examination. Histology Radial scar (sclerosing duct hyperplasia). No evidence of malignancy. A 63-year-old asymptomatic woman. First screening study. Physical Examination No palpable tumor, no history of previous trauma. Mammography Fig. 62 a, b: MLO and CC projections. A large area with architectural distortion is seen 4 cm from the nipple. The mammographic appearance of the lesion changes with the projection. The two hollow, benign-type calcifications are not associated with the lesion. Analysis An invasive ductal carcinoma of this size would have a large, solid central tumor mass. Instead, there are central radiolucencies in both projections, particularly in Fig. 62 a. The radiating structure consists of long, thick, drooping linear densities intervening with radiolucencies. The mammographic image is unlike the straight speculations of an invasive breast cancer. Unlike large breast cancers, this lesion was not palpable, nor was there skin thickening or retraction. Conclusion Typical mammographic and clinical picture of a radial scar. Complete surgical removal is recommended without preoperative needle biopsy (see p. 104). Histology Radial scar (sclerosing duct hyperplasia) without associated epithelial cell proliferation. No evidence of malignancy. Fig. 62 c: Operative specimen photograph. Comment An invasive ductal carcinoma similar in size to Cases 61–64 would be palpable and would have a large, dense, homogeneous central tumor mass dominating the picture (compare Case 60 with Cases 61–64). Asymptomatic 69-year-old woman. First screening study. Physical Examination No history of trauma, no palpable tumor. Mammography Fig. 63 a: Left breast, detailed view of the MLO projection. There is a large radiating structure in the upper half of the breast. Fig. 63 b, c: Left breast, microfocus magnification views, MLO and CC projections. Analysis (Best from the Microfocus Magnification Views) No solid tumor center is demonstrable in this radiating structure. The radiating structure consists of thick collections of linear densities bunched together. Alternating with them are radiolucent linear structures parallel to these strands. There are no associated calcifications. Conclusion Typical mammographic appearance of a radial scar. Comment Even with such a large, superficial lesion, no tumor could be palpated. This supports the diagnosis of a radial scar. Histology Radial scar. No evidence of malignancy. Age 52 years, referred for pain in the right breast. Physical Examination No palpable tumor in either breast. Mammography Fig. 64 a: Right breast, MLO projection. 7 cm from the nipple at coordinate A1 there is a radiating structure. Fig. 64 b: Right breast, CC projection. The radiating structure is seen at coordinate A1. Fig. 64 c: Right breast, enlarged view of the lateromedial (LM) projection. Analysis No solid tumor center. The appearance of the lesion changes remarkably with the projection. The radiating structure consists of thick linear radiopaque densities alternating with linear translucencies. Conclusion Typical mammographic appearance of a radial scar, the diagnosis being supported by the absence of palpatory findings. Complete surgical removal is the treatment of choice. Histology Radial scar (sclerosing duct hyperplasia). No evidence of malignancy. Asymptomatic 63-year-old woman. First screening examination. Physical Examination No palpable tumor in the breasts. Mammography Fig. 65 a: Right breast, MLO projection. Fig. 65 b: Right breast, CC projection. Fig. 65 c: Spot microfocus magnification image in the CC projection. A stellate tumor is seen 6 cm from the nipple in the lateral half of the breast. There are no associated calcifications. Conclusion This is a typical mammographic picture of a small infiltrating carcinoma: the solid tumor mass is surrounded by radiating spicules. Since >90% of invasive carcinomas smaller than 10 mm are of histologic grade 1 or 2, fine needle aspiration biopsy may not lead to conclusive diagnosis of malignancy. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy (a single shot through the lesion) provides sufficient preoperative information for treatment planning. Histology Tubular carcinoma. Size 6 × 6 mm. No axillary metastases. Fig. 65 d: Overview of the tumor. (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], 12.5 ×).

Comment

Strategy

Key Case

57

Practice in Analyzing Stellate/Spiculated Lesions and Architectural Distortion on the Mammogram

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree