Fig. 9.1

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Staging System (From Klein et al. [7] based on Dawson [102]) This figure describes potential treatment options, and suggestions for the incorporation of radiotherapy treatment, and trials. CLT cadaver liver transplant, LDLT live donor liver transplant, PST performance status (ECOG), RT radiotherapy, RF radiofrequency ablation

RFA achieves excellent control rates of >90 % for HCC and IHC if lesions are less than 3–3.4 cm in diameter, but local recurrences are more common if tumours are adjacent to large vessels which exert a cooling effect, or are larger than 4 cm diameter [8, 9]. In addition tumours close to the biliary tract or near the diaphragm can be technically demanding to ablate, making the procedure highly operator dependent.

Palliative TACE offers only a modest gain in overall survival compared with best supportive care in advanced HCC and IHC, but can also be used as a bridge to transplant in conjunction with other local ablative options [10, 11].

Systemic chemotherapy with agents such as doxorubicin, cisplatin, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin for HCC has disappointing response rates (5–20 %), and does not prolong survival [12–14]. Newer targeted agents such as Sorafenib (SHARP trial), Sunitinib and Erlotinib are showing promise [15, 16], but are unlikely to be associated with cure in the absence of local ablative therapies. A phase 3 trial comparing sorafenib with sunitinib was stopped early due to safety concerns over sunitinib [17].

Systemic chemotherapy for IHC with Gemcitabine & Cisplatin has a response rate of 30 % [18]. Sorafenib had a response rate of 0 % in a SWOG study [19]. Studies of newer Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors are ongoing.

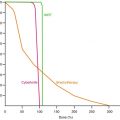

Historically, the role of radiotherapy for liver tumours has been limited by the risk of radiation-induced liver disease (RILD). RILD is characterised by anicteric hepatomegaly, ascites, and elevated alkaline phosphatase occurring within 3 months of liver irradiation [20]. Recently, however, advances in radiotherapy technique (including radiotherapy planning, motion management strategies, and image guidance) have made it possible for radiation to be delivered conformally to partial liver volumes. Dawson et al. analysed over 180 patients and demonstrated that the liver exhibits a large volume effect with a low volume threshold for RILD [21]. Emami et al. have shown that when two-thirds of the liver is irradiated, doses up to 35 Gy are permissible and when only one-third is irradiated, permissible dose increases to 50 Gy [22].

Awareness of this important dose-volume effect, in conjunction with advances in radiotherapy technique, has allowed the development of SBRT techniques for hepatic malignancy.

Radiation therapy has a particularly important role for HCC unsuitable for, or resistant to other locoregional liver directed therapies. Radiotherapy does not feature in many consensus guidelines or documents largely due to a relative lack of Level 1 randomised trial data. However it is also clear that non radiation oncologists currently have a poor understanding of the potential of this rapidly advancing field.

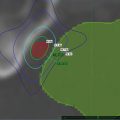

SBRT is a form of high-precision radiotherapy characterised by: reproducible immobilisation; measures to account for tumour motion during treatment planning and delivery; dose distributions tightly covering the tumour, with rapid dose fall off in surrounding normal tissues; and most importantly, the use of relatively few, high dose fractions of radiation (extreme hypofractionation), usually delivered in 1–8 treatments [23].

9.2.1 Summary of Evidence for SBRT in Inoperable HCC

The evidence for SBRT for HCC is largely confined to retrospective series, and prospective phase 1 trials (Table 9.1). SBRT has comparable efficacy with other local therapies and should be considered for early stage HCC unsuitable or refractory to, other liver directed therapies. Use of SBRT to slow progression of HCC whilst awaiting transplantation is growing in popularity although generally has been investigated in patients not suitable or refractory to, other bridging therapies [38, 43]. Pathological complete responses seen after SBRT bridging to transplant demonstrate that SBRT is an effective treatment however Level 1 evidence is urgently required. SBRT can also be considered for Child Pugh B patients unsuitable for standard locoregional therapy, however the risk of radiation induced liver disease (RILD) is higher.

Table 9.1

Trials of SBRT in unresectable HCC

Author [ref] | Year | Number of patients | Dose (Gy), no. fractions | Median volume (cm3) | Median follow up (months) | LC 1 year (%) | LC 2 years (%) | OS 1 year (%) | OS 2 years (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Blomgren et al. [24] | 1998 | 11 | 15–45 in 1 or 3 | 100 | ||||||

Choi et al. [25] | 2006 | 20 | 50 Gy in 5 or 10 | 25 | 23 | 81 | 43 | Retrospective | ||

Mendez Romero et al. [26] | 2006 | 11 | 25 in 5, 30 in 3 or 37.5 in 3 | 22 | 12.9 | 94 | 82 | 75 | 40 | Phase I/II |

Tse et al. [27] | 2008 | 41 | 24–54 in 6 | 173 | 17.6 | 65 | 48 | Phase 1 | ||

Choi et al. [28] | 2008 | 32 | 30–39 in 3 | 25 | 17.3 | 72 | 81 | Retrospective +/− TACE | ||

Seong et al. [29] | 2009 | 37 | 28 | Survey | ||||||

Cardenes et al. [30] | 2010 | 17 | 36–48 in 3, 40 in 5 (CP B) | 34 | 24 | 100 | 75 | 60 | Phase 1 | |

Loius et al. [31] | 2010 | 25 | 45 in 3 | 73 | 15 | 91 | 90 | 79 | 52 | Retrospective |

Seo et al. [32] | 2010 | 38 | 33–57 in 3 or 4 | 40 | 61 | Retrospective, prior TACE | ||||

Kwon et al. [33] | 2010 | 42 | 30–39 in 3 | 15.4 | 28.7 | 72 | 93 | 58 (3 years) | ||

Chan et al. [34] | 2011 | 16 | 45 in 10 | 134 | 24 | 91 | 62 | 28 (3 years) | ||

Andolino et al. [6] | 2011 | 60 | 40 in 5 (CP-B), 42 in 3 (CP-A) | 27 | 90 | 67 | Retrospective | |||

Bujold et al. [35] | 2011 | 102 | 24–54 in 6 | 15 | 79 | |||||

Ibarra et al. [36] | 2012 | 21 | 21–45 in 3 | 334 | 7.8 | 63 % | 87 | 55 | Retrospective | |

Huang et al. [37] | 2012 | 36 | 25–48 in 4 or 5 | 14 | 88 | 75 | 64 | Retrospective | ||

Katz et al. [38] | 2012 | 18 | 50 in 10 | 63 | 19.6 | 100 | Bridging | |||

Sanuki et al. [39] | 2013 | 185 | 35–40 in 5 | 24 | 91 (3 years) | 70 (3 years) | Retrospective | |||

Takeda et al. [40] | 2013 | 63 | 35–40 in 5 | 31 | 100 | 95 | 100 | 87 | ||

Bujold et al. [41] | 2013 | 102 | 24–54 in 6 | 283 (PTV) | 17 | 87 | ||||

Kang et al. [42] | 2012 | 47 | 42–60 in 3 (median 57 Gy) | 95 | 69 | Prospective salvage therapy following TACE | ||||

Ibarra et al. [36] | 2012 | 32 (21 HCC) | 21–45 in 3 | 13 | 87 | 55 | Retrospective |

9.3 Liver Metastases

The annual incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) in the US is over 150,000 cases. There are over 50,000 annual deaths. Approximately 80 % of patients with stage IV CRC have liver disease considered unresectable at presentation [44].

Autopsy studies show that 40 % of colorectal cancer patients relapse with liver only metastases [45–47]. Oligometastatic liver disease (that is up to 5 metastases) may be amenable to aggressive local therapy with the potential for long term disease control [48, 49], or even cure [50, 51]. The evidence to support the local ablation of oligometastases is largely single institution retrospective case series, and some small prospective phase 2 trials. There are currently no prospective trials comparing aggressive local therapy with best supportive care.

Surgery has been the gold standard treatment for colorectal liver metastases, with retrospective series reporting 5 year survivals of 25–47 %, [50–54]. However, up to 80 % of patients are not suitable for resection due to the location, size and distribution of metastases, or poor patient performance status, or significant medical co-morbidities. Chemotherapy can downstage inoperable to operable disease in only around 10–20 % of cases [55]. Newer chemotherapy combinations such as FOLFOXIRI, or FOLFOX/FOLFIRI in combination with the biological agents Bevacizumab or Cetuximab can downstage a significantly higher proportion, but at the cost of considerable toxicity. Response rates can be as high as 70 % with triplet combinations. These chemotherapy combinations have also extended median survival in metastatic CRC to 24 months [56].

Thermal destruction by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or microwave for CRC liver metastases gives 3 year survival rates of 30–46 % [57–60]. There are data to suggest that local control of CRC liver metastases is related to survival—Aloia et report a sevenfold increase in the risk of local failure and a threefold increase in the risk of death, in patients treated with RFA rather than surgical resection, despite similar rates of distant intrahepatic and extrahepatic failure in both groups [61]. Chang et al. report also a strong correlation between local control and survival in patients treated with SBRT for liver metastases [62].

Surgical data for resection of non-CRC liver metastases are more limited. However, a large (n = 1,452) retrospective, multi-institutional series has reported a 5 year survival of 36 % and 10 year survival of 23 % for carefully selected non-CRC, with metastases from breast cancer having the best and melanoma and squamous cell cancers the poorest survival [63]. There are some reports of non-CRC having better local control and survival than CRC when treated with SBRT [64, 65].

9.3.1 Evidence Supporting SBRT to Liver Metastases

Currently, the evidence for SBRT for liver metastases is predominantly retrospective case series (Table 9.2), with some prospective phase 1 and 2 trials (Table 9.3). Within the studies there is significant heterogeneity in patient selection, size and number of lesions treated, dose-fractionation, prescription points and dosimetric criteria.

Table 9.2

Retrospective studies of SBRT for liver metastases

Study | n | Vol/number of mets | Histology | Immobilisation/resp motion | Dose | Prescription point | Toxicity | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Blomgren et al. (1995) [66] | 14 | 3–260 mL | CRC (11); anal canal (1); kidney (1); ovarian (1) | SBF/AC | 7.7–45 Gy (1–4 frx) | Periphery of PTV | 2 cases of haemorrhagic gastritis | 50 % response rate |

Wada et al. (2004) [67] | 5 | NR | NR | VM/AC | 45 Gy (3 frx) | 90–100 % isodose | No serious toxicity | 2 year LC 71.2 % |

No RILD | ||||||||

Wulf et al. (2006) [68] | 44 | 9–355 mL | CRC (23); breast (11); ovarian (4); other (13) | SBF/AC | 30–37.5 Gy (3 frx) | 30 Gy: 65 % isodose; others—80 % isodose (covering 95 % of PTV) | No grade 2–4 toxicity | 1 year LC 92 %;2 year LC 66 % |

26 Gy 1 frx | 1 year OS 72 %;2 year OS 32 % (LC for 37.5 Gy: 1 year 100 %; 2 year: 82 %) | |||||||

Katz et al. (2007) [69] | 69 | 0.6–12.5 cm; (median 2.7 cm) | CRC (20); breast (16); pancreas (9) | VM/Resp. gating | 30–55 Gy (5–15 frx) | 100 % isodose with 80 % covering PTV | No grade 3–4 toxicity | 10 months LC 76 % |

Lung (5); other (19) | 50 Gy/5frx preferred | 20 month LC 57 % | ||||||

Median OS 14.5 months | ||||||||

Van der Pool et al. (2010) [70] | 20 | 0.7–6.2 cm (median 2.3 cm) | CRC (20) | SBF/AC | 37.5–45 Gy (3 frx) | 95 % of PTV received prescribed dose | 2 grade 3 late liver enzyme changes; 1 grade 2 rib fracture | 1 year LC 100 % |

2 year LC 74 % | ||||||||

Median survival 34 months | ||||||||

Habermehl et al. (2013) [71] | 90 | 62 (11–333) | 50 % colorectal | VM, AC | 17–30 Gy median 24 Gy single | Grade 1 fatigue, fever, loss appetite, raised transaminases | Median OS 24 months | |

1 year PFS 70 % | ||||||||

Berber et al. (2013) [72] | 153 | 363 mets, GTV of 138.5 ± 126.8 cm3 | 50 % GI | 37.5 ± 8.2 Gy in 5 ± 3 fractions | 1 year LC = 62 % | |||

1 year OS = 51 % | ||||||||

Fumagalli et al. (2012) [73] | 90 | 113 liver mets | 70 % GI | Cyberknife | 45 Gy in 3 | 80 % | G1–3 | LC 1 year 84 %, 2 years 66 % |

2 years OS = 70 % | ||||||||

Lanciano et al. (2012) [74] | 30 | 41 lesions. | 23 mets, 7 HCC | Cyberknife | Varying | G1/2 toxicities | Median FU 22 months | |

2 years LC 75 % (if BED > 100) |

Table 9.3

Prospective studies of SBRT for liver metastases

Study | Design | n | Volume/number of mets | Histology | Immobilisation/resp motion | Dose | Prescript. point | Toxicity | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Herfath et al. (2004) [64] | Ph 1–2 | 35 | 1–132 mL (median 10 ml) | CRC (18); breast (10); other (7) | SBF and VM/AC | Dose escalation: 14–26 Gy (1 frx) | Isocentre, with 80 % covering PTV | No significant toxicity reported | 1 year LC 71 %; 18 month LC 67 % (18 month LC 81 % for Ph2) |

1 year OS 72 %; Med 25 months | |||||||||

Mendez Romero et al. (2006) [26] | Ph 1–2 | 25 (17 liver mets) | 1.1–322 mL (median 22.2 mL) | CRC (14); lung (1); breast (1); carcinoid (1); | SBF/AC | 37.5 Gy (3 frx) | 65 % Isodose | 2 grade 3 gammaGT elevations; | 2 year LC 86 % |

30 Gy (3 frx) in 3 patients to spare OAR | 1 grade 3 asthenia | 2 year OS 62 % | |||||||

1 late portal hypertension | |||||||||

Hoyer et al. (2006) [75] | Ph 2 | 64 (44 liver) | 1–8.8 cm (median 3.5 cm) | CRC only | SBF or VM/AC | 45 Gy (3 frx) | ICRU ref-95 % to CTV and 67 % PTV | 1 liver failure; 2 severe late GI toxicities | 2 year LC 79 % (by tumour) |

2 year LC 64 % (by patient) | |||||||||

Rusthoven et al. (2009) [76] | Ph 1–2 | 47 | 0.75–98 mL (median 14.93 mL) | CRC (15); lung (10); breast (4); ovarian (3); Oes (3); HCC (2); other (10): | VM/ABC or AC | Dose escalation: 36–60 Gy (3 frx) Ph2 60 Gy (3 frx)—36 pts | Isodose covering PTV (80–90 %) | No RILD | 1 year LC 95 %; 2 year LC 92 %; median survival 20.5 months (32 months for breast and CRC p < 0.001). 2 year OS 30 % |

Late grade 3/4 < 2 % | |||||||||

Lee et al. (2009) [65] | Ph 1–2 | 68 | 1.2—3,090 ml (med. 75.9 mL) | CRC (40); breast (12); gallbladder (4); lung (2); anal (2); melanoma (2); other (6) | VM/ABC or AC (AC if resp excursion >5 mm) | Individualised Dose 27.7–60 Gy (6 frx) | Isodose covering PTV (max 140 % in PTV) | No RILD | 1 year LC 71 % |

10 % grade 3/4 acute toxicity | Median survival 17.6 months | ||||||||

No grade 3/4 late toxicity | |||||||||

Ambrosino et al. (2009) [77] | Prospect cohort | 27 | 20–165 mL (median 69 mL) | CRC (11); pancreas (10); breast (2); 1 each of gallbladder, gastric, ovary, lung | Cyberknife™ (with synchrony™ to track US-placed gold fiducials) | 25–60 Gy (3 frx) | 80 % of prescribed dose covered PTV | No serious toxicity | Crude LC rate 74 % |

36.2 % CRC cases—mild-moderate transient hepatic dysfunction. 3.7 % GI bleed; 3.7 % portal vein thrombosis | |||||||||

Goodman et al. (2010) [78] | Ph 1 (HCC and liver mets) | 26 (19 liver mets) | 0.8–146.6 mL (median 32.6 mL) | CRC (6); pancreas (3); gastric (2); ovarian (2); other (6) | Alpha-cradle. | 18–30 Gy (1 frx) | Isodose that covered PTV (65–90 %) | 4 cases grade 2 late toxicity (2 GI, 2 soft tissue/rib) | 1 year local failure 23 % |

Cyberknife™ (with synchrony™ to track US-placed gold fiducials) | Median survival 28.6 months | ||||||||

2 year survival 49 % (mets only) | |||||||||

Rule et al. (2011) [79] | Ph 1 | 27 | 0.75–135 | Colorectal (12) | 30 Gy (3 F) | 24-month LC rates for the 30-, 50-, and 60-Gy cohorts were 56, 89, and 100 % | |||

Liver mets | 50 Gy (5 F) | ||||||||

60 Gy (5 F) | |||||||||

Scorsetti et al. (2013) [80] | Ph 2 | 61 | 76 mets | Colorectal 48 % | Rapidarc VMAT, VM | 60–75 Gy (3 F) | 65 % fatigue | Median FU 12 months (2–26) | |

Liver mets | 7.7–209 | Breast 18 % | 26 % transaminase rise (settle in 3 months) | CR + PR + SD = 95 % | |||||

Gynae 12 % | LC at 6, 12, 22 months = 100, 94, 91 % | ||||||||

Other 22 % | 1 year OS = 84 %, median OS = 19 months |

Patients were often heavily pre-treated with chemotherapy, surgery, or other local ablative therapies [70, 75]. SBRT has historically been used when the liver metastases were no longer amenable to other treatments (i.e. last resort, until recently).

Local control rates are 70–100 % at 1 year, and 60–90 % at 2 years [2] Several factors predicting local control (LC) may be identified, which may help in patient selection for treatment. The most consistently observed correlation with local control is baseline tumour volume [81–85]. Rusthoven et al. report a superior LC rate for tumours less than 3 cm (100 % vs 77 % at 2 years, p = 0.015) [76]. Number of tumours <3 and size <6 cm predicts for better outcome. Also, delivered BED >117 Gy10 is associated with improved local control at 1 year [62]. Metachronous CRC liver metastases has a better prognosis than synchronous [75] Median overall survival is 10–34 months, and 2 year survival ranges from 30 to 83 % [2]. For CRC specifically, Hoyer et al. report a median survival of 1.6 years from SBRT [75]. Out-of-field progression of disease occurs in a substantial proportion of patients, although this is also reported after hepatic resection [48].

There are a number of predictors of overall survival, and long term survival is seen after treatment. Factors associated with increased survival are:

Primary histology. Favourable primary histology includes breast, CRC, renal, carcinoid and GIST. Unfavourable primary sites include lung, ovary and non-CRC gastro-intestinal. Rusthoven et al. report median survival for favourable primary sites as 32 months vs 12 months for unfavourable primaries (p < 0.001) [76]. Lee et al. report superior 1 year survival for CRC (63 %) and breast cancers (79 %) compared to other primary sites (38 %) [65].

Liver SBRT is very well tolerated, both in terms of acute and late toxicity, and may be used safely after other liver directed therapy (surgery or RFA). The means by which liver SBRT has been delivered in published series is variable, but with generally good outcomes. No particular SBRT technique has superior outcomes in terms of tumor control or toxicity. Patient Selection Criteria

For HCC, enhancement typically in the arterial phase on two imaging modalities and α-fetoprotein (AFP) increased on a background of liver disease

Biopsy-confirmed IHC

Unresectable tumour or inappropriate for other treatment modalities, or as a bridge to transplant for HCC

Patients should be discussed in Multi-Disciplinary Tumour Board meetings

Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) ≥60

Life expectancy >3 months

Child-Pugh score: A, or B7/8 (Table 9.4)

Table 9.4

Child-Pugh liver score

Measure

1 point

2 points

3 points

Total bilirubin (μmol/l) (mg/dl)

<34 (<2)

34–50 (2–3)

>50 (>3)

Serum albumin (g/l)

>35

28–35

<28

INR

<1.7

1.71–2.20

<2.20

Ascites

None

Mild

Severe

Hepatic encephalopathy

None

Grade 1–2 (or suppressed with medication)

Grade 3 or 4

Points

Class

One year survival (%)

Two year survival (%)

5–6

A

100

85

7–9

B

81

57

10–15

C

45

35

>700 cc of uninvolved liver

No chemotherapy within 2 weeks prior, and 4 weeks after, SABR

No, or limited and potentially treatable, extra-hepatic disease.

Recovered from any previous therapy (such as surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy to other areas) with a minimum of 2 weeks break (for HCC, anthracycline based chemotherapy should be completed 4 weeks before SBRT)

Up to three metastases, with no limitation on actual size of a given tumour provided functional residual volume, and organ at risk (OAR) dose constraints can be met

Adequate organ function, defined as: Hemoglobin 90 g/L, absolute neutrophil count 1.5, platelets 80, bilirubin <3.0 times upper limit of normal, INR <1.3 or correctable with vitamin K and unless the patient is taking warfarin/coumarin, AST or ALT <5.0 times upper limit of normal. Creatinine less than 200 umol/L (if creatinine is above the normal range consideration should be given to dynamic renal scintigraphy (renography)) if there is anticipated to be any appreciable renal dose from the delivery of treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree