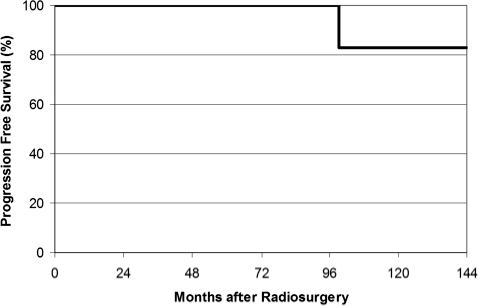

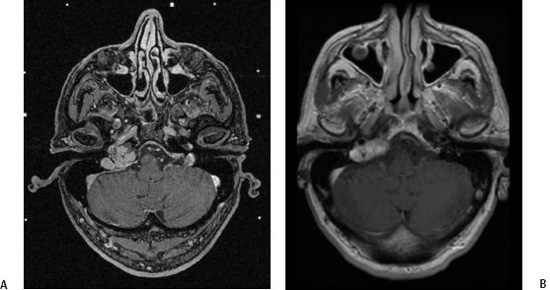

11 Glomus tumors arise from the paraganglia of the chemoreceptor system and occur in both intracranial and extracranial locations. Glomus tumors represent ~0.01% of all tumors diagnosed in humans.1–3 Greer et al reported an incidence of 8.6 cases per 100,000 new patients.4 Glomus jugulare tumors and glomus tympanicum lesions are the two most common sites of intracranial occurrence. Women are affected approximately 2 to 5 times more frequently than are men. Local invasion of adjacent structures and the effect of tumor mass cause symptoms associated with this tumor. Neurovascular structures within the hypoglossal canal, jugular foramen, and temporal bone can be affected. Their intimate association with the lower cranial nerves and inner ear complicates their management, because injuries to these structures can cause significant morbidity and functional disability.5 The optimum treatment of glomus tumors remains controversial. Although the majority of tumors are histologically benign, these tumors are characterized by unpredictable biological behavior. Typically arising from glomus bodies located in the dome of the jugular bulb, this neoplasm is intimately associated with critical neurovascular structures at the skull base. Successful treatments have included surgical resection, embolization, external beam fractionated radiotherapy (EBFRT), and a combination of these modalities.4,6 Early treatment of patients with glomus tumors focused on limited resection combined with radiation therapy or radiation therapy alone. The relative inaccessibility of the jugular bulb region, the potential for damage to the surrounding structures, and the vascular nature of these tumors dictated a treatment that was, for the most part, consistent with palliation. Surgery has been most frequently performed in young patients or for patients with complete loss of cranial nerve function. Gross total surgical resection has been accomplished in 0 to 90% of cases in reported series.7–14 EBFRT has been used in elderly patients and for symptomatic tumors that were considered unresectable, were incompletely resected, or had recurred after resection.15–18 Control of glomus tumors after EBFRT has ranged from 85 to 100%, with complication rates of 0 to 10%. Complications associated with EBFRT have included necrosis of the temporal bone or brain, mastoiditis, and other local tissue injury. As an alternative to surgical resection or EBFRT, radiosurgery has been used to manage patients with glomus tumors in the hope of achieving high tumor control rates and symptom response similar to those seen with EBFRT.19–32 Radiosurgery is commonly performed for patients with benign intracranial tumors, and long-term growth control has been demonstrated for patients with vestibular schwannomas and meningiomas.33,34 Improved neuroimaging and dose-planning software has contributed greatly to the reduction in cranial nerve deficits after radiosurgery of skull base tumors. Radiosurgery has less general radiation exposure compared with EBRT, and radiosurgery is typically performed in a single session rather than over 5 to 6 weeks. In 1999 Eustacchio et al reported 10 patients having radiosurgery for glomus tumors.19 Radiosurgery was the primary treatment for the majority (n = 7) of the patients. At a median follow-up of 37.6 months, four patients had tumors that decreased in size, whereas six patients had tumors that remained stable. In a series published by Jordan et al in 2000, eight patients who were deemed unsuitable for surgery were treated with stereotactic radiosurgery.25 The mean follow-up duration was 27 months, and no patient had an increase in the size of the tumor. One patient experienced intractable vertigo requiring hospitalization after radiosurgery. Saringer et al reported on 13 patients in 2001, with none showing evidence of tumor growth.30 Two patients experienced radiation-induced cranial neuropathies, both of which were transient. More recent studies have supported the findings of early reports on the efficacy and safety of glomus tumor ra-diosurgery.20,21,23,26,31,32 Of note, four patients from the Cleve-land Clinic series (23%) showed evidence of tumor expansion after radiosurgery.32 Three out of these four patients improved clinically. Likely this finding relates to the methodology used to determine tumor size after radiosurgery. In this series, volumetric analyses of tumor volumes were calculated rather than simply comparing linear measurements before and after radiosurgery. The phenomenon of temporary tumor expansion after radiosurgery is well documented after vestibular schwannoma radiosurgery and is not an indicator of a failed procedure.35 In 1997 Foote et al published our first report on glomus tumor radiosurgery.22 This preliminary study evaluated the acute and intermediate toxicities associated with radiosurgery for patients with unresectable or subtotally resected glomus tumors. No radiation-induced complications were noted, and eight of nine tumors remained stable in size at a median follow-up duration of 20 months. More recently, Pollock reported on 42 patients with glomus tumors who underwent Gamma Knife (Elekta Instruments AB, Stockholm, Sweden) surgery at the Mayo Clinic.29 The mean follow-up for 39 evaluable patients was 44 months (range 6–149). After radiosurgery, 12 tumors (31%) decreased in size, 26 tumors (67%) were unchanged, and 1 tumor enlarged. This patient underwent repeat radiosurgery. The progression-free survival (PFS) rate after radiosurgery was 100% at 3 and 7 years and 75% at 10 years. Six patients (15%) developed new deficits (hearing loss: n = 3; facial numbness and hearing loss: n = 1; vocal cord paralysis and hearing loss: n = 1; temporary imbalance/vertigo: n = 1). For 26 patients with testable hearing before radiosurgery, hearing preservation was achieved in 86% and 81% at 1 and 4 years, respectively. No patient developed a new lower cranial nerve deficit after single radiosurgery; the patient having repeat radiosurgery had a new vocal cord paralysis 1 year after his second procedure. Between March 1990 and October 2007, 57 patients with glomus tumors underwent Gamma Knife surgery at our center. The mean patient age was 58.5 years (range 18–88). Twenty-three patients (40%) had undergone one or more tumor resections prior to surgery. We used an average of 8.1 isocenters of radiation (range 1–19) to cover a mean tumor volume of 14.1 cc (range 1.2–70.3). The mean tumor margin dose was 15.3 Gy (range 12–18); the mean maximum radiation dose was 32.2 Gy (range 24–40). Imaging follow-up was available in 54 patients at a mean of 48 months after the procedure. Fifty-three tumors either decreased (n = 14, 26%) or were unchanged (n = 39, 72%) in size after radiosurgery (Fig. 11.1). One patient showed tumor progression 99 months after radiosurgery and underwent repeat radiosurgery. There has been no evidence of tumor progression after his repeat procedure. Overall, PFS in our series is now 100% at 3 and 7 years and 83% at 10 years (Fig. 11.2). Fig. 11.1 Axial postgadolinium magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a 62-year-old man diagnosed with a right-sided glomus jugulare tumor after developing hoarseness and tongue weakness. (A) MRI at the time of radiosurgery. The tumor margin dose was 16 Gy. (B) MRI 84 months after radiosurgery showing the tumor to be decreased in size. A summary of the studies on glomus tumor radiosurgery published after 1999, including our updated information, shows a tumor growth control rate of 94% (Table 11.1

Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Glomus Tumors

Jeffrey T. Jacob, Michael J. Link, Robert L. Foote, and Bruce E. Pollock

Radiosurgery for Glomus Tumors

Radiosurgery for Glomus Tumors

Rationale for Radiosurgery

Early Reports

Mayo Clinic Experience

Recent Reports

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree