and Gustavo Marino2

(1)

Attending Physician VA Medical Center, George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

(2)

Chief Gastroenterology Section VA Medical Center, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

3.1.1 Anatomy

3.1.2 EUS Probes

3.1.3 Technique

3.1.4 Preparation

3.2.1 Gastric Cancer

3.2.12 Gastric Carcinoid

3.2.13 Gastric Lipoma

3.2.15 Pancreatic Rest

3.2.17 Perigastric Abscess

Abstract

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a well-established method used in the evaluation of gastric lesions. This procedure provides information that is key for the diagnosis and management of patients with gastric lymphomas, adenocarcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), and subepithelial lesions, among others.

3.1 General Principles

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a well-established method used in the evaluation of gastric lesions. This procedure provides information that is key for the diagnosis and management of patients with gastric lymphomas, adenocarcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), and subepithelial lesions, among others.

EUS as a staging modality for gastric malignancies has been extensively evaluated, and it is an excellent modality to obtain a histologic/cytologic diagnosis in cases that are otherwise difficult to diagnose for diagnostic or staging purposes. A clear knowledge of technique, indications, appropriate interpretation of findings, and limitations is fundamental for EUS practice.

3.1.1 Anatomy

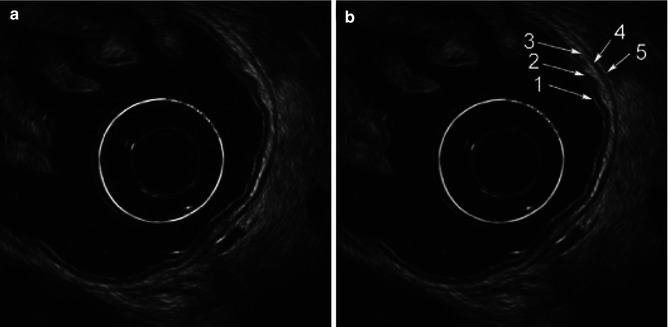

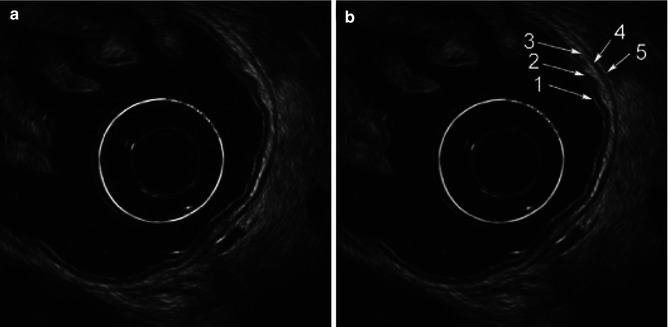

EUS can assess the layers of the gastric wall, determining the layer of origin of many lesions as well as the deepest level of local involvement. A pattern of five layers of the gastric wall is easy to recognize with standard EUS endoscopes:

Layer | EUS appearance | Anatomic correlation |

|---|---|---|

First | Hyperechoic (echorich) | Interface between the lumen and mucosa (superficial mucosa) |

Second | Hypoechoic (echopoor) | Deep mucosa |

Third | Hyperechoic (echorich) | Submucosa |

Fourth | Hypoechoic (echopoor) | Muscularis propria |

Fifth | Hyperechoic (echorich) | Serosa |

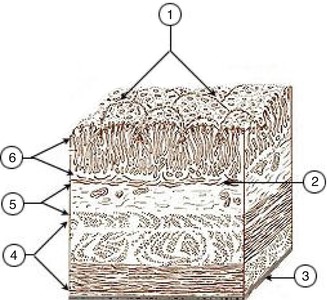

Fig. 3.1

Endoscopic ultrasound images of a normal gastric wall with a five-layered structure using an SU-8000 system (a, b). 1 first hyperechoic layer, 2 second hypoechoic layer (mucosa), 3 third hyperechoic layer (submucosa), 4 fourth hypoechoic layer (muscularis propria), 5 fifth hyperechoic layer (subserosa and serosa) (From Akahoshi [1])

3.1.2 EUS Probes

EUS examination of the stomach is usually performed with flexible radial scanning echoendoscopes, which provide optimal staging information for gastric malignancies. Miniprobes are also available in some centers and are ideal for the evaluation of small superficial or subepithelial lesions since they have a higher frequency (12–20 MHz) and provide greater resolution. Their disadvantage is that they have limited depth of evaluation and therefore are not recommended for larger lesions.

Linear EUS endoscopes have recently become the echoendoscope of choice for some endoscopists, although many endosonographers still prefer the radial scanning probes for the initial exam. Linear EUS endoscopes allow fine-needle aspiration (FNA) if necessary.

3.1.3 Technique

It is ideal to cover areas of interest with water to enhance acoustic coupling. To better evaluate these areas, air has to be aspirated completely. Air bubbles in the water covering the lesion may also interfere with EUS imaging; suction and repeat filling with water may be necessary to remove these air bubbles. However, some areas, including the cardia, fundus, anterior wall, and lesser curve of the antrum, may be difficult to evaluate. Position changes including supine, right lateral decubitus, or Trendelenburg (flat on the back with the feet higher than the head) may be helpful to cover these areas with water, although these changes may increase the risk of aspiration and patients may need airway protection. Use of an EUS balloon is therefore necessary in some cases to facilitate the examination and minimize the risk of aspiration.

Endoscopic visualization of lesions in the wall of the stomach with oblique view endoscopes allows the endoscopist to position the EUS probe to obtain appropriate sonographic evaluation. This endoscopic visualization should be done with the least amount of air distension possible, preferably under water, to enable optimal acoustic coupling. Recent EUS scopes and electronic consoles allow electronic control of the focal distance; this feature is not available with EUS miniprobes or older models, and in these cases it is important to place the probe at an optimal distance from the wall to obtain a detailed examination of the gastric layers.

To obtain appropriate measurement of wall or lesion thickness, ultrasound waves should approach the wall perpendicularly. Excessive compression should also be avoided; this can impair visualization of subtle lesions or distort the interface between wall layers.

3.1.4 Preparation

EUS evaluation is done with standard preparation for upper endoscopy. Patients are placed in the left lateral decubitus position. Position changes with water filling of the stomach should be done carefully, and appropriate airway protection should be provided to avoid aspiration.

Box 3.1: Resources

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Soft Tissue Sarcoma http://www.globalgist.org/docs/NCCN_guidelines.pdf

American Cancer Society: Cancer facts and statistics http://www.cancer.org/Research/CancerFactsFigures/index

Paris staging system for primary gastrointestinal lymphomas (Gut 2003) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1773680/pdf/gut05200912.pdf

Small gastric lymphoma diagnosed by EUS images (YouTube) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OWC7-1ar5W0

3.2 Cases and Discussions

3.2.1 Gastric Cancer

This is an 87-year-old Japanese woman who was referred for the evaluation of a gastric abnormality. Eighteen months before this presentation a gastric polyp was biopsied and showed only adenoma. The patient returned to her physician again 3 months before her referral to us and again the biopsies showed adenoma. The referring physician felt uneasy with this situation and the patient was referred for EUS. The lesion turned out to be rather large (3.2 cm). Repeat biopsies were performed with the Radial Jaw® 4 Jumbo Biopsy Forceps (Boston-Scientific), and invasive adenocarcinoma was found.

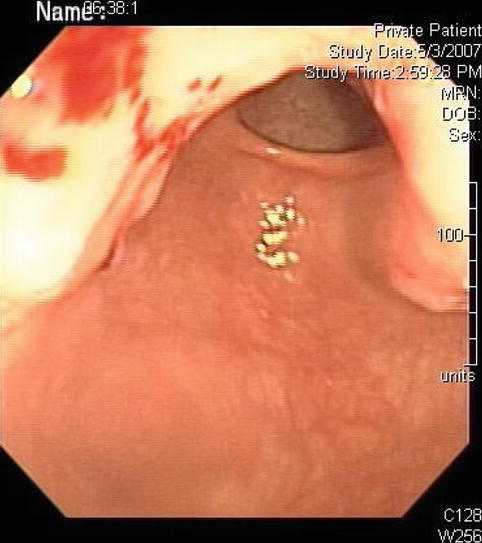

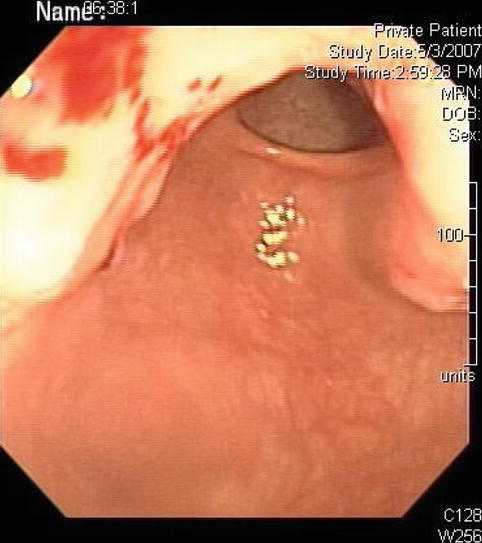

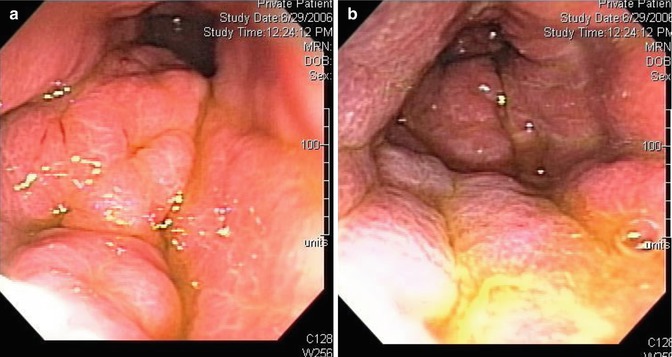

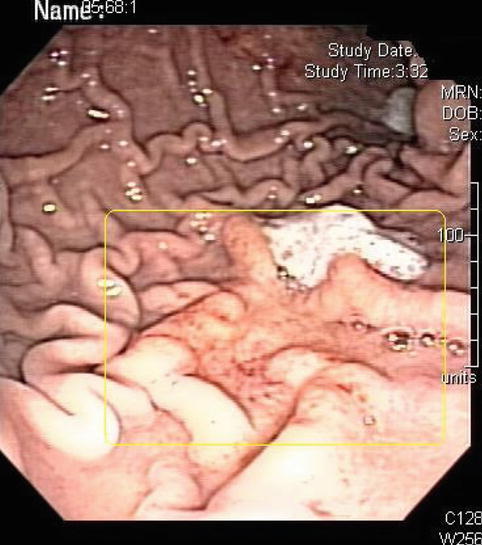

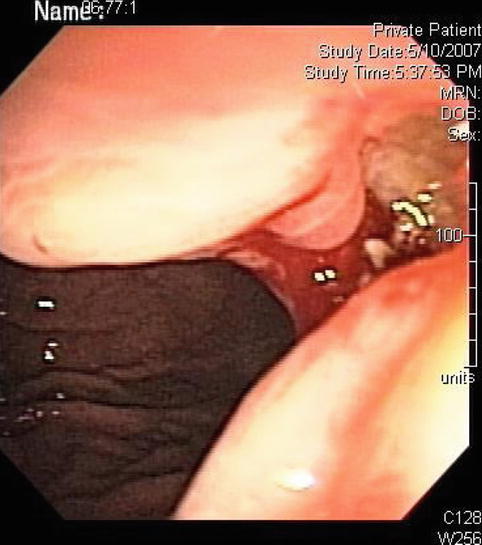

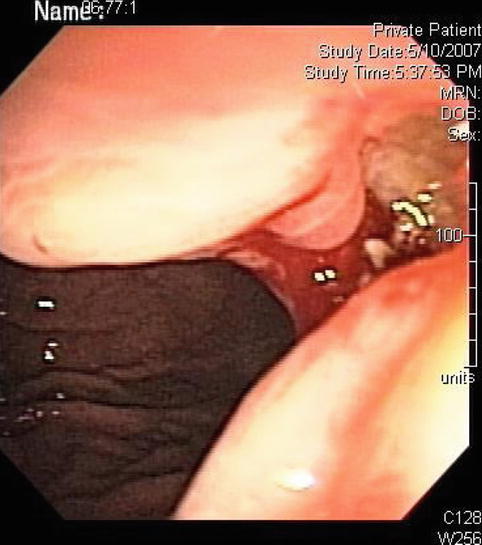

Fig. 3.2

This is how the adenocarcinoma appeared on esophagogastroduodenoscopy

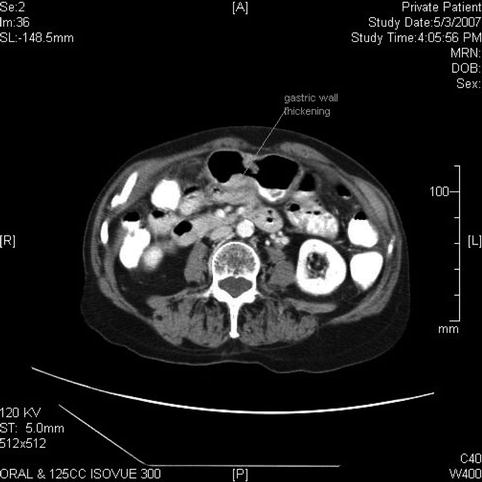

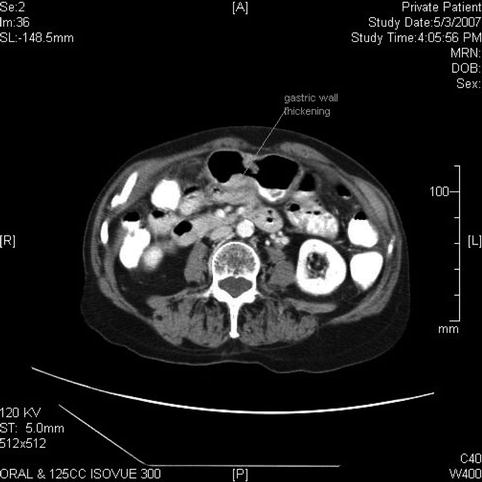

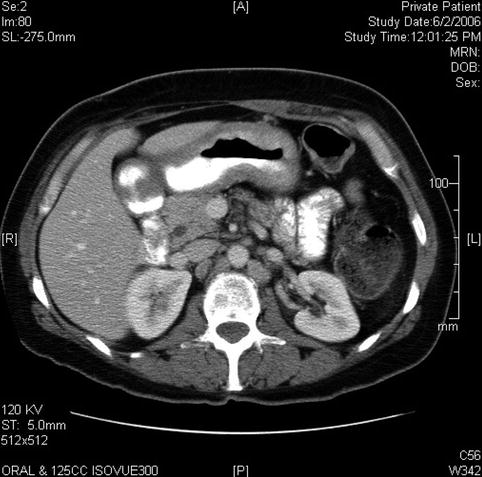

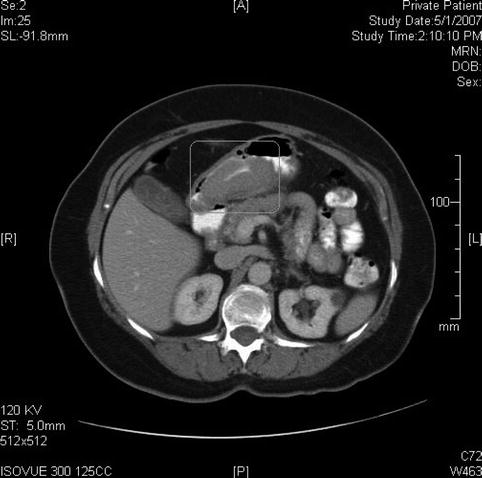

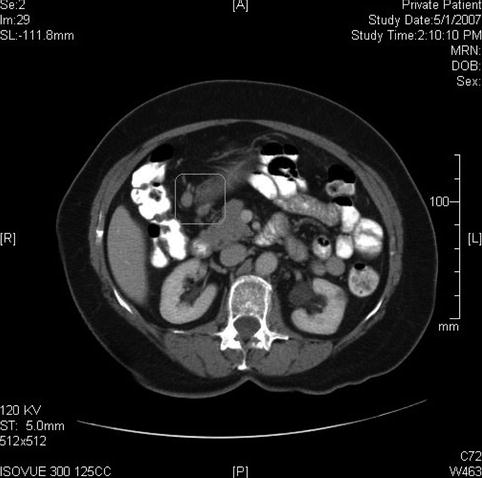

Fig. 3.3

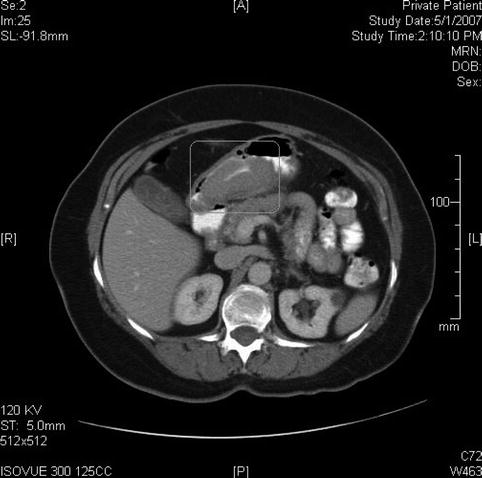

Nonspecific thickening of the gastric wall is seen on this computed tomography scan, which was obtained after the endoscopic ultrasound to rule out distant metastasis

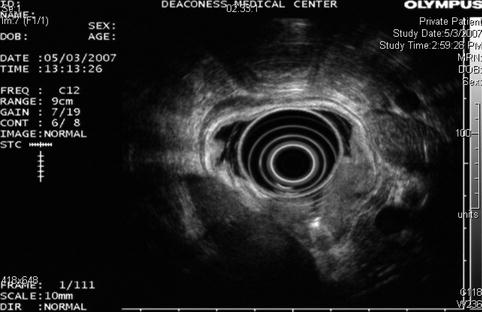

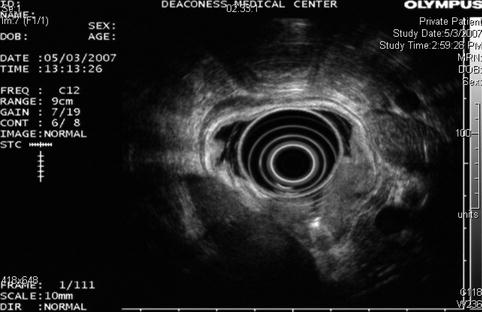

Fig. 3.4

The endoscopic ultrasound shows a gastric cancer obliterating the muscularis propria (T3)

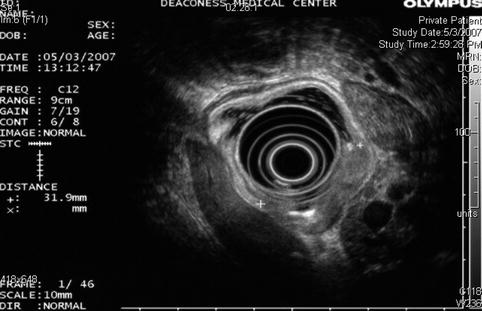

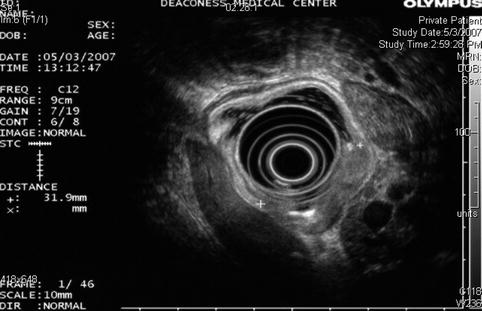

Fig. 3.5

A different endoscopic ultrasound image of the same gastric cancer. No lymphadenopathy was seen

In the United States, gastric cancer ranks 14th in incidence among the major types of malignancies, with approximately 21,320 new cases per year and 10,540 deaths estimated in 2012 [2]. The site of origin within the stomach has changed in frequency in the United States over recent decades. The incidence of tumors of the distal half of the stomach have been decreasing in the Western world since the 1930s, with the incidence of cancer of the cardia and gastroesophageal junction increasing over the past two decades. This elderly patient from Japan, however, illustrates the exception. For reasons not entirely clear but probably related to diet, the incidence of distal gastric cancers remains high in Japan, Chile, and Iceland.

Staging of this disease is critical; unfortunately, in the United States most patients have advanced disease at presentation and therefore their prognosis is poor. However, if detected at an early stage, the management of gastric cancer can be successful. Patients with early gastric cancer (T1 mucosal disease) can be resected endoscopically and patients with T1–T3 locoregional disease without distant metastases are candidates for surgical resection [3].

EUS is considered the most accurate preoperative test for T staging; however, its actual accuracy for T staging varies between 57 and 92 % [3]. EUS is more accurate with advanced disease. Accuracy of N staging using EUS has been reported between 50 and 87 %, with results similar to computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance.

Ulcerated lesions may cause fibrosis and inflammatory changes that cannot be differentiated from actual tumoral invasion by EUS [4, 5]. Inflammatory changes indistinguishable from cancer on EUS can also be found after chemotherapy, and therefore this technique is not recommended to assess response after neoadjuvant therapy [6].

3.2.2 Linitis Plastica of the Stomach

This 58-year-old man presented with nausea and weight loss. Initial endoscopy showed thickened gastric folds suspicious for the condition but biopsies (performed on two separate occasions) were nondiagnostic. On the basis of the CT and EUS appearance, linitis plastic was strongly suspected and the patient referred for laparotomy, at which time the diagnosis was confirmed with a full-thickness biopsy.

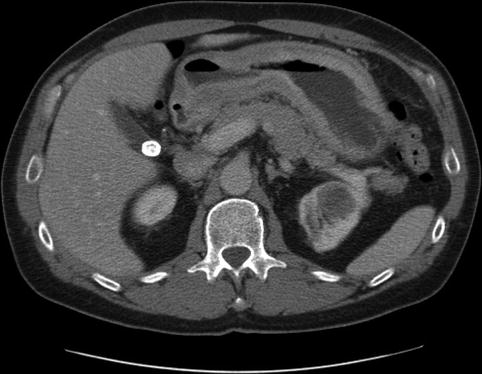

Fig. 3.6

A markedly thickened gastric wall on computed tomography

Fig. 3.7

Linitis plastica. The mucosa measures 11 mm, the muscularis 4 mm, green line mucosa and submucosa; yellow line muscularis propria

Fig. 3.8

The antral wall is thickened to 12 mm and uniformly hypoechoic

Linitis plastica is a diffuse infiltration of the wall of a hollow viscus with severe desmoplastic response, fixing the superficial layers to the muscularis propria and producing a rigid, thickened appearance of the organ. In the stomach this has been called “leather bottle” and is found in up to 10 % of adenocarcinomas, although it can also be secondary to metastatic disease such as infiltrating lobular breast carcinoma [7]. The prognosis is generally poor.

Endoscopically the stomach appears rigid and nondistensible. It affects the antrum and pyloric regions more commonly than the fundus. EUS findings include increased wall thickness (>6 mm) and loss of architecture of the gastric layers.

The superficial gastric mucosa is frequently spared and the malignant cells can be scarcely distributed in the fibrous stroma, making the endoscopic diagnosis challenging [8]; endoscopic biopsies are negative for malignancy in up to a third of cases of linitis plastica adenocarcinomas [9, 10]. Additional endoscopic techniques to obtain a better yield include “tunnel” biopsy, in which biopsies are taken at the same site to obtain deeper samples, and large particle biopsy, in which a fragment of a thickened fold is resected with a diathermic snare or EUS-guided FNA [10].

3.2.3 Linitis Plastica with Bone Metastases

This is a 48-year-old woman who was found to have a single bone lesion, which biopsy found to be metastatic adenocarcinoma. Subcarinal lymph node enlargement was found on a chest CT scan. EUS-guided FNA was requested. The lymph nodes seen during the examination with the linear EUS instrument were rather unimpressive. Instead, a markedly abnormal-appearing gastric mucosa was encountered both by surface endoscopy and ultrasound. The CT scan also showed impressive thickening of the gastric wall. The stomach was biopsied twice, once with a regular biopsy forceps and subsequently as a large particle biopsy performed with a polypectomy snare. Both samples were nondiagnostic.

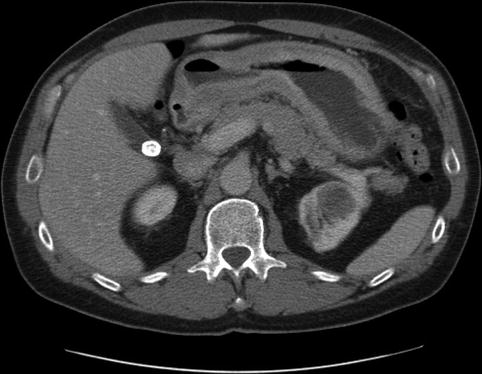

Fig. 3.9

Linitis plastica: Appearance of the gastric mucosa on esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Fig. 3.10

The marked thickening of the gastric wall is apparent on this linear endoscopic ultrasound image

Fig. 3.11

Marked thickening of the wall of the stomach on a computed tomography scan

Fig. 3.12

Several months later multiple bone metastases are apparent on this pelvic computed tomography scan

Linitis plastica is a proliferative condition of the connective tissue. It is triggered by the presence of malignant signet-ring cells, which spread diffusely through the layers of the gastric wall. Malignant cells are usually absent from otherwise grossly abnormal-appearing gastric mucosa. The mucosal layer can be so expanded that even very aggressive biopsies do not get to the layer that contains the malignant cells. Ordinary cancers that originate from the mucosa and spread partially through the muscularis propria without eliciting a connective tissue response of this sort should not be called linitis plastica.

3.2.4 Stage 1 Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma

This is a 59-year-old patient with a history of a peptic ulcer that had healed when viewed on follow-up endoscopy. However, the endoscopist noted severe hemorrhagic-appearing gastritis along the greater curvature. Biopsies showed an “increased amount of intraepithelial lymphocytes,” and a process such as a mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma could not be ruled out. The patient was referred for EUS evaluation and repeat biopsies, which were performed with the Radial Jaw® 4 Jumbo Biopsy Forceps (Boston-Scientific), and a battery of immunostains confirmed the presence of a low-grade MALT lymphoma.

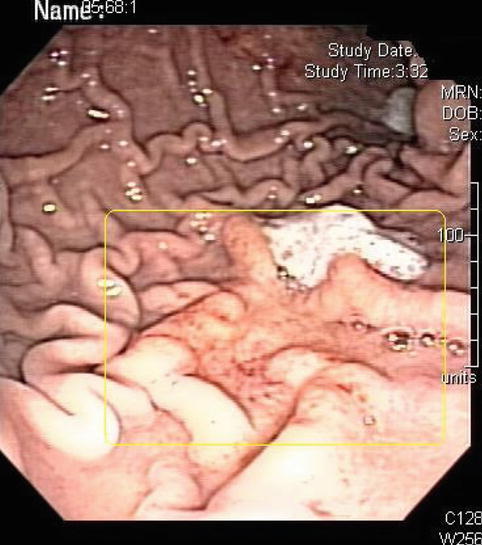

Fig. 3.13

In this mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue case the mucosal layer is subtly expanded

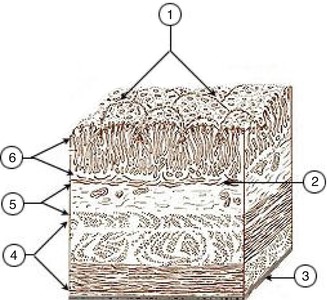

Fig. 3.14

Typically the mucosa occupies one third of the gastric wall thickness (Wikimedia Commons)

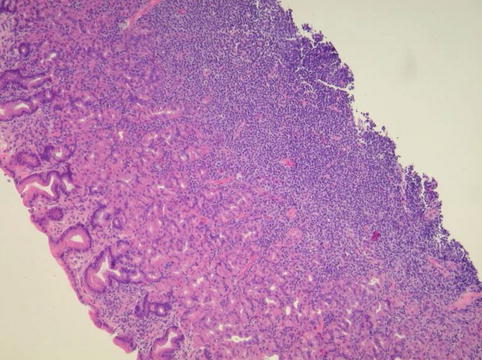

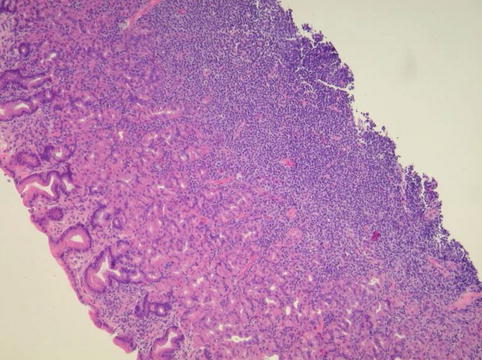

Fig. 3.15

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of the gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma shows the dense infiltrate of small lymphocytes

Fig. 3.16

Eight weeks after eradication of the Helicobacter pylori organism the area involved by “gastritis” had receded to approximately. 5 cm in diameter, as shown here

In the new World Health Organization classification of lymphoid tumors, MALT lymphomas are more correctly called “extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas.” This is because there is now strong evidence to suggest that the type of cell from which the lymphoma develops is a specific B-cell that is found in a compartment of the lymphoid tissue called the marginal zone.

Lymphomas represent approximately 5 % of all gastric malignancies, and the most common of them are extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas. Ninety percent of these gastric MALT lymphomas are associated with the presence of Helicobacter pylori. These patients will have a monoclonal B-cell infiltration as opposed to the polyclonal response seen in chronic gastritis; additional immunohistochemistry is necessary to differentiate it from other gastric B-cell lymphomas such as mantle cell, lymphocytic gastric, and follicular gastric lymphomas [11]. EUS-guided FNA can be helpful in establishing the diagnosis of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in up to 89 % of suspicious cases with inconclusive endoscopic biopsies, as shown by Wiersema et al. [12].

There is no generally agreed-upon staging protocol or classification scheme for gastric MALT lymphomas. Adapted versions of the Ann Arbor staging system, such as the Lugano modification of the Blackledge staging scheme [13] and the adapted version of Musshoff’s modified Ann Arbor staging system [14], have been used for this purpose; more recently the Paris staging system [15] was developed for gastrointestinal lymphomas (the Paris classification is available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1773680/pdf/gut05200912.pdf). The latter allows stratifying patients using a TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) scheme. T staging in this classification is based on the deepest layer involved, which can be estimated by EUS. Regardless, EUS is considered the most accurate locoregional method of staging [3].

The spectrum of MALT lymphomas ranges from involvement of the mucosa layer alone to all layers of the gastric wall and spread to the lymph nodes and spleen. Increasing depth of invasion through the stomach wall is closely correlated with decreasing responsiveness to treatment to eradicate H. pylori. Other EUS-based studies have shown that involvement of the regional lymph nodes is associated with considerably reduced response rates to either antibiotics to eradicate H. pylori or conventional lymphoma treatment; response in T1N0 disease is approximately 75 %, decreasing to 50 % in T1N1 and 25 % in T2N0 disease.

The role of EUS in the evaluation of response to therapy or as a surveillance method to detect relapsing MALT lymphoma is controversial; some authors have documented a long time lag between histological and endosonographic remission and sonographic normalization despite histologically ongoing disease [16].

3.2.5 MALT Lymphoma with Local and Distant Lymph Node Involvement

This is a 78-year-old patient who had complained of unprovoked vomiting several weeks before her referral for endoscopy. All of her symptoms have resolved and she now feels well.

Endoscopy showed a deep ulcer associated with abnormal surrounding tissue along the lesser curvature of the stomach. Biopsies showed MALT lymphoma confirmed by immunohistochemistry. A CT scan showed what initially was interpreted as a mass in the cecum, but colonoscopy was normal. In fact, what was seen were distant lymph node metastases. There were also enlarged regional perigastric lymph nodes, which were well demonstrated on EUS. Per the World Health Organization classification, this MALT lymphoma is more appropriately called extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. In this case with regional and distant nodal metastasis. Less than 10 % of patients with MALT lymphoma have distant lymph node involvement, and up to 30 % may have regional lymphadenopathy.

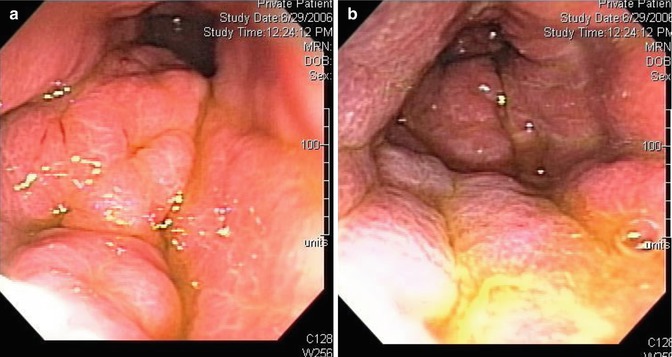

Fig. 3.17

This deep gastric ulcer seen on upper endoscopy with surrounding thickened mucosa turned out to be secondary to a mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma

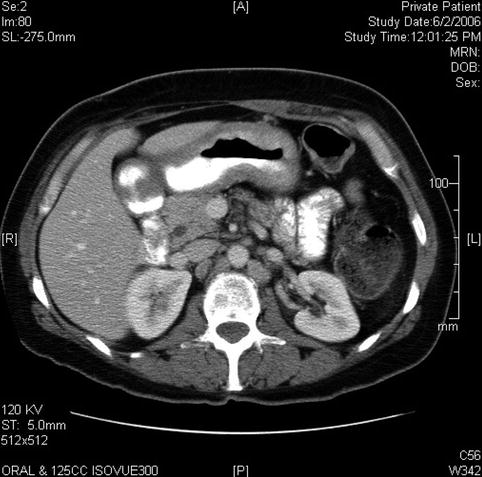

Fig. 3.18

On this computed tomography scan a large gastric mass is seen; in fact, it appears much larger than appreciated on endoscopy

Fig. 3.19

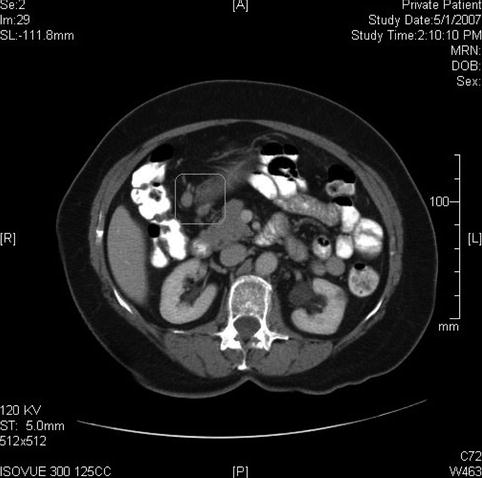

This computed tomography scan shows perigastric lymph node enlargement

Fig. 3.20

A right lower quadrant lymph node conglomerate is also present. This was initially interpreted as a cecal mass

Fig. 3.21

The endoscopic ultrasound image demonstrates transmural involvement of the gastric wall by the lymphoma

Fig. 3.22

Perigastric lymphadenopathy as seen by endoscopic ultrasound

3.2.6 Subepithelial Gastric Tumors

Subepithelial gastric tumors include lesions that arise from the gastric wall but are covered by normal mucosa; therefore they can originate from deep mucosa to serosa. Subepithelial lesions are commonly found on endoscopy, although most of them are asymptomatic. Unfortunately, it is difficult to establish their malignant potential by endoscopy alone, and EUS has become the study of choice to narrow the differential diagnosis. EUS can exclude extrinsic compression and vascular lesions; determine their nature (solid vs. cystic), and allow tissue sampling.

Differential diagnosis of subepithelial gastric lesions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|