Fig. 22.1

Macroscopic photo of the heart at autopsy demonstrates hydatid cyst filling the left ventricle as a cause of sudden death (From Byard (2009), with permission)

As a rule, left-sided cysts tend to grow subepicardially, while right-sided cysts have a tendency to expand subendocardially (Dursun et al. 2008). There are five patterns of hydatid disease of the heart: (1) dead calcified cysts, (2) living intact cysts, (3) ruptured pericardial cysts, (4) pediculated intracavitary cysts, and (5) ruptured intracavitary cysts (Peters et al. 1945). A ruptured cyst is a serious complication of cardiac hydatidosis. It is important to know that right ventricular cyst rupture leads to pulmonary embolus, severe anaphylactic shock, or sudden death (Dursun et al. 2008). The ruptured hydatid cyst results in systemic emboli in organs supplied by the aortic circulation such as the (1) brain (64 %), kidney (17.5 %), spleen (17.5 %), and liver (1 %) (Peters et al. 1945).

Clinically, the following sequential stages of the hydatid disease develop after direct rupture of a primitive cyst of the heart:

1.

Onset stage, characterized by general malaise with signs of anaphylaxis ranging from only a rash to an allergic shock

2.

Asymptomatic stage, characterized by embolic dissemination of the parasite into various organs in the body through the pulmonary or systemic aortic circulation

3.

Metastatic stage, characterized by development of pulmonary or visceral secondary hydatidosis within the host

4.

Complication stage, characterized by development of various complications such as bacterial infection of the pericyst cavity, related to the secondary localization of the hydatidosis (Deve 1946)

Importantly, it has been noted that the aforementioned four stages are independent of the location of the rupture (intracavitary, intramyocardial, or intrapericardial) (Thameur et al. 2001). It has been reported that the intrapericardial location occurs as a result of rupture of a primitive hydatid lesion (Dursun et al. 2008). The early diagnosis and treatment of cases with cardiac hydatidosis during the initial phase of rupture characterized by the history of allergic reactions is very important to prevent possible fatal risk of rupture. As expected, the diagnosis of cardiac hydatid cyst is easy when the secondary location is symptomatic (Thameur et al. 2001).

In the cases of cardiac hydatidosis, chest pain and cough are the most common initial signs, followed by fever, arrhythmias, cardiac syncope, acute myocardial infarction, pulmonary hypertension, pericarditis, pulmonary embolism, anaphylactic shock, or unexpected death (Aleksic-Shihabi and Vidolin 2008). The sudden death in cases with cardiac hydatidosis results from “obstruction” of the chambers of the heart or “embolism” of pulmonary or carotid arteries by migrated cyst fragments, following intracavitary rupture of the cyst in the right or left heart (Thameur et al. 2001).

The symptoms and signs depend on the anatomical location of the hydatid embolus, including the cerebral arteries, the abdominal aorta, or its branches including the extremity arteries. Imaging studies such as plain radiography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasonography (US) provide very useful information for the diagnosis of cardiac hydatid disease, although echocardiography (EC) remains the most efficient diagnostic method (Aleksic-Shihabi and Vidolin 2008). In clinical practice, hydatid cyst of the heart is generally sterilized before removal with 30 % hypertonic saline solution or other scolicidal agents including 0.1–1 % cetrimide, 2 % formalin, 1 % iodine, or 0.5 % silver nitrate (Maroto et al. 1998).

Cerebral Hydatidosis

Cerebral hydatid cyst can be single fertile “primary” containing hydatid sand or multiple metastatic “secondary,” which is sterile and does not have a germinative layer, due to spontaneous, surgical, or traumatic rupture of a primary cyst (Fig. 22.2) (Turgut and Bayülkem 1998; Turgut 2001, 2002; Byard 2009). It is well known that the sterile cysts do not form secondary cysts in case of rupture, if no sand is present in the cyst (Haddad and Haddad 2005). Nevertheless, there is no consensus as to the route the larvae take from the gut to the brain for primary hydatidosis: the larvae reach the right heart through the inferior vena cava and the brain in case of a patent septal cardiac foramen or arteriovenous channels in the lung (Haddad and Haddad 2005). On the other hand, as described above, secondary cysts in the brain result from the rupture of the primary cysts localized in the left compartments of the heart.

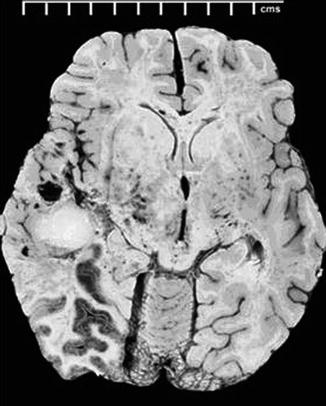

Fig. 22.2

Macroscopic photo of the brain at autopsy reveals a large hydatid cyst in the left temporal lobe (From Byard (2009), with permission)

In general, the clinical picture is dominated by the symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (IICP) with or without hydrocephalus in children, while in adults, the focal neurological signs related to infarcts or cysts located in the watershed of the abovementioned cerebral arteries, such as hemiparesis, epileptic seizures, and aphasia, are usually the first to appear (Abada et al. 1977; Turgut and Bayülkem 1998; Turgut 2001, 2002). It has also been reported that children with multiple hydatid may present with focal neurological signs (Turgut and Bayülkem 1998; Turgut 2001, 2002).

Neuroimaging modalities, such as CT and MRI, are the most valuable diagnostic tools for diagnosing cerebral hydatid disease. Typically, hydatid cyst has a density similar to that of cerebrospinal fluid on CT scans and MRI (Haddad and Haddad 2005). It is important to know that multiple cysts are more often seen in cases secondary to cardiac embolization through the vascular system (Turgut et al. 1997). In some cases with hydatidosis, the pericyst layer may be calcified owing to the calcium deposition, and there is no peripheral enhancement of the cyst. Recently, it has been suggested that the differentiation of fertile and sterile cysts may be possible with proton MR spectroscopy (Garg et al. 2002).

Today, the treatment of choice is surgical removal of the cysts if possible. In complicated cases, various techniques including tapping of the cyst and injection of a devitalizing solution such as formalin or hypertonic saline other than the Dowling-Orlando technique may be useful before removal of the cyst (Turgut 2001). Rupture of the cyst into the subarachnoid space as complication of surgery may result in severe anaphylactic response (Buris et al. 1987).

Anthelmintics are recommended in patients with multiple cysts and in those unfit for surgery or suffering from recurrent disease (Turgut and Bayülkem 1998; Turgut 2001, 2002). In such instances, anthelmintics such as mebendazole, liposomal and tablet albendazole, or praziquantel should be administered during the perioperative period, although the efficacy of medical treatment is questionable in hydatidosis. Nonetheless, large and symptomatic cysts should be surgically treated first, and the patient should be closely followed up for the need for reoperation in the future.

Stroke as a Complication of Cardiac Hydatidosis

“Stroke” as a complication of cardiac hydatidosis, a cause of ischemic or hemorrhagic infarction and multiple metastatic cyst formations, is an extremely rare entity (Byard and Bourne 1991; Turgut et al. 1997; Turgut and Bayülkem 1998). It results from spontaneous, traumatic, or surgical rupture of a fertile cardiac cyst and embolization of the germinative membrane, scolices, or portions of endocyst. Basically, there are two pathological types of “stroke” from cardiac embolization: (1) acute obstruction of a cerebral artery, partial or complete, with a piece of embolized cyst membrane and (2) development of multiple cyst formations in the infarcted area following embolism of scolices during the course of several months. In young patients with the diagnosis of stroke, subsequent development of “cerebral cyst” within the necrotic area of the brain tissue, called “cerebral infarct,” strongly suggests embolism of ruptured cardiac hydatid cysts (Figs. 22.3 and 22.4) (Benomar et al. 1994; Lotfinia et al. 2007). As a rule, the cerebral embolism called “stroke” usually occurs when portions of a ruptured hydatid cyst travel from the left side of the heart to the brain (Turgut et al. 1997). For this reason, a routine investigation for cardiac hydatidosis as a possible source of a cerebral embolus should be undertaken, if patient has hydatid disease in other organs.

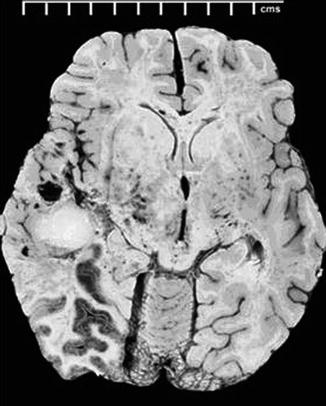

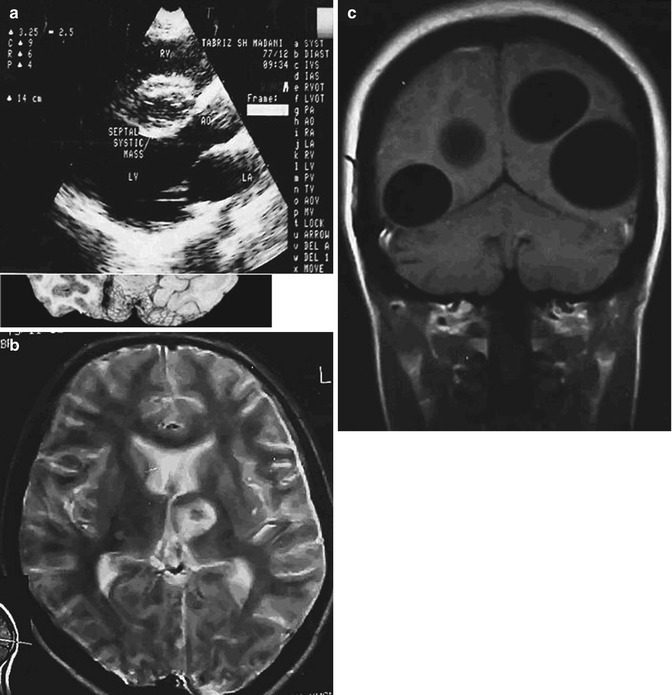

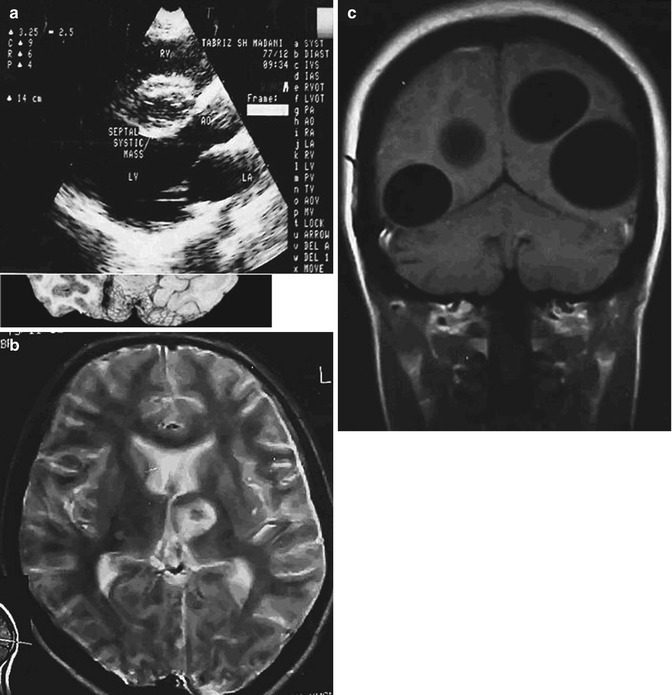

Fig. 22.3

Development of cyst in a previously infarcted region of the brain following hydatid occlusion of the cerebral artery. (a) CT shows infarct (arrow) of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA). (b) Angiogram demonstrates occlusion of the left MCA. (c) CT displays cystic lesions (arrows) in the infarcted region of the brain (From Benomar et al. (1994), with permission)

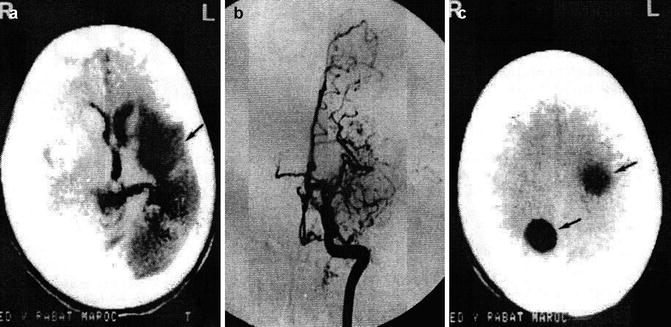

Fig. 22.4

Stroke as a complication of cardiac hydatidosis with an interval of 2 years between infarction and cyst formation. (a) Echocardiography shows a cystic mass in the ventricular septum of the heart. (b) Axial T2-weighted MRI demonstrates hyperintense cystic foci in the left basal ganglia. (c) Axial T2-weighted MRI shows multiple cystic cerebral lesions in both hemispheres (From Lotfinia et al. (2007), with permission)

We reviewed the scientific literature for all published articles containing cases of “stroke” as a complication of cardiac hydatidosis with/without multiple metastatic hydatid cysts of the brain published to date. In this review, all published case reports, case series, and abstracts found in congress abstract books on stroke as a complication of cardiac hydatidosis were included. If a case appeared in more than one paper on this subject, the earlier report was omitted. Also, dubious cases with no data available to the authors were excluded (Gessini and Giammusso 1957; Preda et al. 1963; Thameur et al. 2001; Díaz and Maillo 2002). Altogether, 41 articles were selected, containing 41 cases of “stroke” as a complication of cardiac hydatidosis with/without multiple metastatic hydatid cysts of the brain (Peters et al. 1945; Paillas et al. 1962; Chin et al. 1981; Vaquero et al. 1982; Petrov 1987; Borisenko et al. 1990; Byard and Bourne 1991; Benomar et al. 1994; Talaslioglu et al. 1994; el Quessar et al. 1996; Turgut et al. 1997; Evliyaoglu et al. 1998; Kabbaj et al. 1998; Marcì et al. 1998; Ugur et al. 1998; Maffeis et al 2000; Ulgen et al. 2000; Kemaloğlu et al. 2001; Cakir et al. 2002; Trehan et al. 2002; Singh et al 2003; Acarturk et al. 2004; Bükte et al. 2004; Karabay et al. 2004; Pillai et al. 2004; Yaliniz et al. 2004; Itumur et al. 2006; Yaliniz et al. 2006; Lotfinia et al. 2007; Aleksic-Shihabi and Vidolin 2008; Ašanin et al. 2008; Goz et al. 2008; Kumar and Hasan 2008; Byard 2009; Kanj et al. 2010; Kojundzic et al. 2010; Sabouni et al. 2010; Cansu et al. 2011; Ekici et al. 2011; Fabijanić et al. 2011; Potapov et al. 2011). Nevertheless, the cases cited in this chapter do not constitute all of those in the literature because of the unsuitability of some of the reports for proper analysis and the inaccessibility of certain papers. The details of the 41 cases of “stroke” as a complication of cardiac hydatidosis with/without multiple metastatic hydatid cysts of the brain are listed in Tables 22.1 and 22.2.

Table 22.1

Summary of the 41 reported cases with stroke as a complication of cardiac hydatidosis published in the world literature to date: demographic data and cardiac findings

Author(s) | Country | Year of publication | Patient age (years), sex | Systolic murmur | EC | Location of cyst(s) in the heart | Other organ involvement | Result of serological study | Type of rupture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Peters et al. | USA | 5, F | NS | NS | LVe | Liver | NS | Spontan | |

24, M | NS | NS | LAe | NS | NS | Spontan | |||

45, F | NS | NS | LA, P, IVS, LVe | Kidney, spleen, thyroid, ICA, MCA, superior mesenteric artery, renal artery, splenic artery | NS | Spontan | |||

Paillas et al. | France | 17, M | (−) | NS | LVe | ICA, eyeball, foramen ovale | NS | Spontan | |

Chin et al. | Australia | 37, M | NS | (−) | P | (−) | (+) | Spontan | |

Vaquero et al. | Spain | 37, M | NS | (−) | P, LV | NS | NS | Surgical | |

Petrov | Bulgaria | 32, M | NS | (−) | LVe | (−) | NS | Spontan | |

Borisenko et al. | USSR | 11, F | (+) | (+) | LV | (−) | (+) | Spontan | |

Byard and Bourne | Australia | 7, M | NS | (−) | LV | Liver | NS | Spontan | |

Talaslıoglu et al. | Turkey | 19, F | NS | (+) | NS | NS | NS | Spontan | |

Benomar et al. | Morocco | 21, F | NS | (−) | P, LA, LV | Kidney, liver, spleen | NS | Spontan | |

40, F | NS | (+) | LV | Kidney, liver, spleen | (+) | Spontan | |||

el Quessar et al. | Morocco | 21, F | NS | (−) | P, LV | Kidney, liver, spleen | NS | Spontan | |

40, F | NS | (+) | LV | Kidney, liver, spleen | (+) | Spontan | |||

Turgut e al. | Turkey | 7, F | (+) | (+) | LV | Femoral artery | NS | Spontan | |

Ugur et al. | Turkey | 18, F | NS | (−) | IVS | NS | NS | Spontan | |

Kabbaj et al. | Morocco | 28, M | NS | (+) | LV | Kidney, liver | (+) | Spontan | |

Evliyaoglu et al. | Turkey | 24, M | NS | (+) | LV | NS | NS | Spontan | |

Marci et al. | Italy | 26, F | (+) | (+) | LV | (−) | (+) | Spontan | |

Ulgen et al. | Turkey | 70, M | NS | (+) | IVS, LV | Liver | (+) | Spontan | |

Maffeis et al. | Brazil | 57, M | NS | (+) | LV | NS | NS | Spontan | |

Kemaloglu et al. | Turkey | 7, F | NS | (+) | LV | NS | NS | Spontan | |

Cakir et al. | Turkey | 6, F | (−) | (+) | LV | (−) | (+) | Spontan | |

Trehan et al. | India | 13, M | (+) | (+) | RA, LA, IAS | Liver | (−) | Spontan | |

Singh et al.a | India | 13, M | (+) | (+) | RA, LA, IAS | Liver | (+) | Spontan | |

Acarturk et al. | Turkey | 15, M | NS | (+) | LV | Liver, abdominal aorta | NS | Spontan | |

Pillai et al. | UAE | 36, F | NS | (+) | LV | Eyeball | NS | Spontan | |

Karabay et al. | Turkey | 19, M | NS | (+) | IAS, RA, LA | Liver | NS | Spontan | |

Yaliniz et al. | Turkey | 16, M | NS | (+) | LV | Liver | (+) | Surgical | |

Bükte et al.b | Turkey | 7, F | NS | (+) | LV | NS | NS | Spontan | |

Itumur et al. | Turkey | 24, M | (+) | (+) | LV | (−) | NS | Spontan | |

Yaliniz et al.c | Turkey | 16, M | NS | (+) | LV | Liver | (+) | Surgical | |

Lotfinia et al. | Iran | 17, F | (+) | (+) | S | (−) | NS | Spontan | |

Aleksic-Shihabi and Vidolin | Croatia | 27, M | (+) | (+) | LV, P | (−) | (+) | Surgical | |

Kumar and Hasan | India |