Abstract

Imaging is recommended only in the aggressive so-called necrotizing variant of external otitis, seen in diabetic patients. Acute otomastoiditis and coalescent mastoiditis with subperiostal abscess formation are almost exclusively seen in children. In chronic otomastoiditis, CT is used to evaluate the ossicular chain and otomastoid walls, whereas MRI using non-echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging is performed to detect the underlying cholesteatoma. Labyrinthitis is seen, respectively, uni- and bilaterally in the case of tympanogenic or meningogenic origin, and in three stages: acute, fibrous, and ossifying. MRI enables diagnosing facial neuritis in the depth of the internal auditory meatus and along the first segment of the nerve.

Keywords

Cholesteatoma, External otitis, Labyrinthitis, Otomastoiditis

Acknowledgments

I thank Nancy Verpoort who spent a considerable amount of time editing the figures and texts.

Introduction

In a wide variety of inflammatory and infectious diseases of the temporal bone, imaging studies are used to determine the extent of the disease and to visualize eventual complications. Imaging protocols for the evaluation of infections in the external ear, the middle ear (and mastoid), and the inner ear are somewhat different, and the interpretation of the images must be done from different viewpoints. In some situations, CT or MRI is the best choice; in others, both techniques are used for different reasons.

External Ear: External Otitis

External Otitis

External otitis is common and can be caused by exposure to polluted water, after trauma (e.g., after the use of cotton swabs), and in a variety of dermatologic diseases. The ear is painful and itches. Diagnosis is in most cases easy, just by inspection or rarely by using an otoscope. Only occasionally imaging is required. On CT, external otitis is seen as a narrowing of the external ear canal that contains a soft tissue opacification ( Fig. 5.1 ). Purely on the basis of imaging the finding is aspecific and cannot be distinguished from any soft tissue obliteration of another origin.

Necrotizing External Otitis

Necrotizing external otitis, also referred to as malignant external otitis, is a severe infection almost exclusively caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . The term “malignant” has also been used because of the aggressive behavior of the disease, rapidly spreading from the external ear canal to the ipsilateral deeper soft tissues and bony structures, such as the mastoid, temporomandibular joint, and parotid gland, but the disease can even proceed as far as in the parapharyngeal space or end up as an extensive zone of osteomyelitis of the skull base, rarely with intracranial extension. Necrotizing external otitis is almost exclusively seen in the diabetic or immunocompromised patient, sometimes in the elderly. Besides local signs of external ear inflammation with otorrhea, ototalgia is the most common symptom.

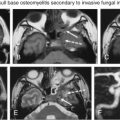

CT and MRI are both able to visualize the disease, but MRI is superior to provide a detailed view on the exact extent of the disease. On CT, opacification of the external ear canal is seen, as well as bony erosion and destruction of the canal walls and mastoid, and eventually the temporomandibular joint or deeper parts of the skull base, such as the clivus. Pathologic enhancement of the soft tissues surrounding the temporal bone is present, and in more pronounced stages of the disease abscess formation occurs. On MRI the same disease pattern is recognized, but a better contrast resolution leads to a better delineation of the soft tissue changes ( Fig. 5.2 ). Bone marrow changes are also well appreciated on MRI. The most common finding on MRI is infiltration of the fat behind the mandibular condyle. Treatment consists of a combination of surgery with intravenous antibiotics.

Middle Ear and Mastoid: Otomastoiditis

Acute Otomastoiditis and Coalescent Mastoiditis

The middle ear and mastoid are an extension of the upper respiratory tract. Bacteria can infect the middle ear via the Eustachian tube, and can subsequently infect the mastoid antrum and the adjacent pneumatized portions of the petrous bone via the aditus ad antrum. In the case of a mild infection, pain is present and the tympanic membrane is hyperemic. In moderate cases of otomastoiditis, imaging is of no additional value to the clinical findings of the otologist, and a conservative therapy will help. If such an acute infection, however, persists too long, resorption of the ossicles and the mastoid occurs and mastoid cells coalesce, and the term “coalescent mastoiditis” is used. This condition is almost always seen in children. Four clinical signs are indicative of advancing acute mastoiditis: pain and erythema in the mastoid region, tenderness, swelling in the postauricular region with auricle protrusion, and edema of the posterosuperior wall of the external auditory canal. In almost all of these patients the ipsilateral eardrum is inflamed and immobile and bulges.

When this process of coalescence becomes more pronounced, the wall of the tympanic cavity and/or mastoid can be destructed, leading to several severe complications, such as the formation of a subperiostal abscess, thrombosis of the sigmoid sinus, brain abscess, meningitis, or acute bacterial labyrinthitis. The last one is also referred to as otogenic labyrinthitis and is unilateral (contrary to meningogenic labyrinthitis, which is by rule bilateral). The manifestation of labyrinthitis is discussed later. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common pathogen causing severe intracranial complications, followed by Streptococcus pyogenes .

Temporal bone CT is an excellent technique for the diagnosis of acute coalescent mastoiditis, by demonstrating the air cell septa breakdown, the breakthrough of the sigmoid bony plate, and the lateral cortical wall of the mastoid. Subperiostal abscess is present in half of the patients with coalescent mastoiditis. It is at this point important to make CT images in a soft tissue setting to demonstrate the abscess ( Fig. 5.3 ). MRI can also very well demonstrate such an abscess. In the past, mastoid subperiostal abscess required mastoidectomy, but owing to the use of improved antibiotics the actual treatment consists of tympanostomy with tube insertion, intravenous antibiotics, and postauricular incision with abscess drainage, avoiding morbidity and complications of mastoid surgery in children. Thrombosis of the sigmoid sinus, brain abscess, and meningitis have become increasingly uncommon. MR is the modality of choice to image these conditions. The sigmoid sinus thrombus is spontaneously T1 hyperintense before intravenous (iv) injection of gadolinium and does not enhance after iv injection of gadolinium ( Fig. 5.4 ). An otogenic abscess is not different from a nonotogenic brain abscess and often shows diffusion restriction on MR. Meningitis leads to thickening and increased enhancement of the meninges. Occasionally, late complications are noted, such as ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint ( Fig. 5.5 ).

Petrous Apicitis

The petrous apex is the most anterior and medial portion of the temporal bone. It articulates with the clivus and is pneumatized to a variable degree, depending on the amount of other pneumatized air cells in the temporal bone. Pneumatization of the petrous apex is present in 33% of all temporal bones. In such a pneumatized petrous apex infection can occur. On CT images the petrous apex becomes opacified, and on MR images classic signs of infection are seen: heterogeneous high signal on T2-weighted image (T2WI), heterogeneous low signal on T1-weighted image (T1WI), and heterogenous enhancement after intravenous injection of gadolinium ( Fig. 5.6 ). MR enables the differentiation of petrous apicitis from other entities encountered in the petrous apex, such as cholesterol granuloma and cholesterol cyst. How this differentiation can be done is discussed in another dedicated chapter in this book. The frequency of petrous apicitis has decreased with the appropriate use of antibiotics in the treatment of middle ear infections. Nowadays it is extremely rare to see petrous apicitis become aggressive, leading to nasopharyngeal or neck abscess formation or facial nerve paralysis.

Chronic Otomastoiditis Without Cholesteatoma

The natural history of chronic otomastoiditis differs almost completely from acute otomastoiditis. Acute otomastoid disease traditionally develops in well-pneumatized mastoids of children, whereas chronic otomastoiditis usually occurs in a temporal bone with a sclerotic mastoid. Imaging is not mandatory in all patients with chronic otomastoiditis but is well indicated in a preoperative setting in the case of difficult otoscopy or doubtful diagnosis, suspicion for a present malformation, single functional ear, temporal bones after mastoidectomy, and suspicion for the presence of intracranial complications.

A wide variety of CT changes is observed in the case of chronic inflammatory/infectious disease of the middle ear and mastoid. These changes occur at the level of the tympanic membrane or in the middle ear cavity. CT can give some information on the tympanic membrane, but the otoscopy is of course able to appreciate such tympanic membrane changes much better, so the CT examination is more dedicated to the evaluation of the various middle ear changes, such as the opacification of the cavity, ossicular chain erosions, and phenomena causing fixation of the ossicular chain, such as formation of fibrous tissue, calcification, or even ossification.

The tympanic membrane is often thickened in the case of chronic otomastoiditis or is perforated. These changes are often seen clearly on CT, but the otologist will for sure be more interested in what is seen behind the membrane. Retraction of the tympanic membrane is another phenomenon often seen in the chronically inflamed middle ear, and this can sometimes lead to confusing CT findings whereby the membrane is positioned on the stapes, whereas the malleus and incus are excluded from the process of sound conduction. In more extreme circumstances, mostly in the case of a coexisting cholesteatoma, the ossicular chain can be absent as a result of autoevacuation and the retracted membrane is positioned on the oval window. The cholesteatoma is also evacuated, but its matrix is not ( Fig. 5.7 ).