TEMPORAL BONE: NONINFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

KEY POINTS

- Imaging in noninfectious inflammatory diseases is often nonspecific for diagnostic purposes but can suggest their possibility.

- Imaging can help to suggest the next best step(s) in the diagnostic process.

- Infectious skull base problems must be excluded on some basis up to and including a therapeutic trial of antimicrobials that will cover both fungal and bacterial infections if tissue sampling and culture is not definitive.

INTRODUCTION

Etiology

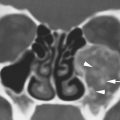

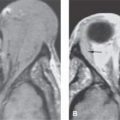

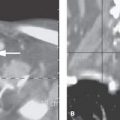

Wegener granulomatosis (WG) (Chapter 17) occasionally manifests in the temporal bone and/or related nerves, likely due to extension from the nasopharynx (Figs. 17.4 and 116.1). Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) (Chapter 19) will most commonly involve the mastoid and middle ear (Figs. 19.1, 19.2, and 116.2). Sarcoidosis can involve the middle ear and mastoid, petrous apex, and surrounding dura as well as the facial and cochleovestibular nerve. Tuberculosis rarely involves the skull base and is usually associated with other pulmonary or other manifestation lesions and is actually an infectious granulomatous process1 (Figs. 110.10 and 115.7). Autoimmune diseases associated with vasculitis can cause labyrinthitis. Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder rarely may involve the temporal bone (Fig. 26.10)

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The prevalence and epidemiology of these diseases is discussed in conjunction with those specific entities in Chapters 17 through 20 and 26.

Clinical Presentation

These inflammatory diseases will be most often discovered as additional sites of disease in a patient with an already established diagnosis. If not, they will typically mimic cancer or infectious disease of the temporal bone such as necrotizing otitis externa (Chapter 114) and skull base osteomyelitis (Chapter 115). This is particularly true of the isolated form of LCH presenting as a lytic bone lesion or WG and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder that may involve the petrous apex, spreading there from the nasopharynx.2 Disease presenting as a primary temporal bone lesion may require an extended period to diagnose precisely, as the earliest manifestations may be indistinguishable from much more common benign diseases such as otitis media with effusion.

Pathophysiology

Anatomy

The anatomy of interest is that of the entire temporal bone and posterior skull base, described in detail in Chapter 104. In particular, the detailed anatomy of the external auditory canal and petrotympanic fissure must be understood to evaluate the disease properly in its early stages (Figs. 104.21–104.23). It is also useful to understand the relationship of the surrounding anatomy, including the temporomandibular joint, nasopharynx (Chapter 184), and masticator and parapharyngeal spaces (Chapter 142).

Pathology and Patterns of Disease

The pathophysiology of these diseases are discussed in conjunction with those specific entities in Chapters 17 through 20 and 26.

Pathologically Altered Function

These may cause conductive, sensorineural, or mixed hearing loss. Eustachian tube dysfunction is a common finding. More extensive lesions can cause cranial neuropathies. Inner ear dysfunction secondary to labyrinthitis and intracranial and vascular complications occur. The likelihood of such dysfunction depends on the disease mechanism and location in the temporal bone.

IMAGING TECHNIQUES

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

Specific protocols for computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) studies for investigating inflammatory temporal bone pathology appear in Appendixes A and B. This problem may be studied initially with dedicated contrast-enhanced CT or contrast-enhanced MR of the temporal bone. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used first if the presentation is primarily that of facial or cochleovestibular dysfunction. Computed tomographic angiography and computed tomographic venography or MR angiography and MR venography are typically not required and generally are not useful for medical decision making.

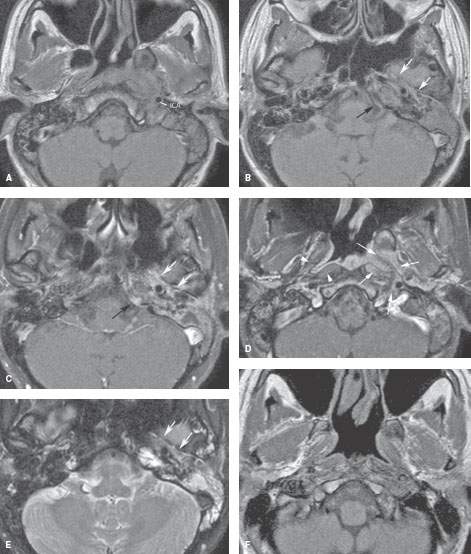

FIGURE 116.1. Wegener granulomatosis. The patient presented with a 6-month history of left-sided fullness of the ear, pain and hearing loss, and weight loss. A–E: Pretreatment magnetic resonance imaging showing a nasopharyngeal mass on the left spreading along the carotid (ICA) in the retrostyloid parapharyngeal space and along the cartilaginous and bony eustachian tube (white arrows in B and E) to the middle ear. The mass enhances slightly on fat-suppressed images (C, D) as it infiltrates the prevertebral and parapharyngeal spaces (arrows in D) compared to the normal side (arrowheads in D). There is some enhancing dural thickening at the petrous apex (black arrow in C). A nasopharyngeal biopsy was inconclusive. The patient developed renal insufficiency and skin lesions. A positive circulating antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA) test confirmed Wegener disease. F, G: A follow-up study 16 months later showed regression of the soft tissue mass with some residual scarring beneath the skull base.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree