Cryptorchidism

2.5–14× increased risk

Personal history of testicular cancer

20× increased risk of contralateral tumor

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia

Up to 50 % of patients develop invasive tumor

Genetic disorders

Klinefelter syndrome, Down syndrome, abnormal short arm of chromosome 12

Family history

6× increased risk if testicular cancer in first-degree relative

White race

5× increased risk compared with black individuals

Supernumerary nipples

4.5× increased risk

Histology and Tumor Markers

Germ cell tumors account for 95 % of testicular cancers and are divided into seminomatous or nonseminomatous subtypes, each comprising approximately 40–45 % of germ cell tumors, with the remaining being mixed [2]. Nonseminomatous tumors usually contain more than one cell type and may include seminoma mixed with other germ cell neoplasms such as embryonal cell carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, yolk sac tumor, and teratoma. Serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) can help distinguish patients with pure seminoma from those with mixed tumors as it is only secreted by nonseminomatous tumors. AFP levels are elevated in 20 % of patients with clinical stage I disease and in more than 50 % of patients with metastases [1]. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is less specific as it can be elevated in both seminomatous and nonseminomatous tumors. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels are used in both tumor types as a marker of disease burden, as it is elevated in more than 50 % of patients with advanced disease. Non-germ cell tumors of the testis include lymphoma, Sertoli, and Leydig cell tumors [2]. Tumor histology is determined by radical orchiectomy, which involves resecting the testis and ligating the spermatic cord at the inguinal ring (see Table 6.2).

Germ cell tumors | 95 % of testicular tumors | |

Seminoma 40–45 % | ||

Nonseminomatous tumors* 40–45 % | ||

Mixed malignant germ cell tumors† 10 % | ||

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia–precursor lesion | ||

*Embryonal carcinoma | Elevated AFP and/or β-hCG | |

*Yolk sac carcinoma | Elevated AFP | |

*Choriocarcinoma | Elevated β-hCG | |

*Teratoma | Mature or immature elements | |

†Mixed tumors | One or more histologic subtype of nonseminomatous tumor with or without seminoma | |

Sex cord and stromal tumors | 90 % benign | |

Leydig cell tumor–stromal tumor | ||

Sertoli cell tumor–sex cord tumor | ||

Granulosa cell tumor | ||

Fibroma–thecoma | ||

Leydig cell tumor | Most common, 30 % hormonally active producing androgens or estrogens | |

Mixed germ cell and sex cord stromal tumor | Gonadoblastoma | |

Lymphoid | Lymphoma ∼4 % of testicular tumors | Patients >60 years old, B cell lymphoma |

Other | Sarcoma | |

Metastasis | ||

Testicular Cancer Staging

Testicular cancer staging is based on local tumor extent, presence and size of regional nodes, serum tumor marker levels, and distant metastases (see Table 6.3) [1]. Local disease is divided as limited to testis and epididymis (T1), involving testis and epididymis with vascular/lymphatic invasion or tumor extension through the tunica albuginea to tunica vaginalis (T2), tumor invading spermatic cord (T3), and tumor invading scrotum (T4) [1]. Stage I tumors can range from T1 (stage Ia disease) to T4 (stage Ib or Is) but have no nodal or distant metastases. Stage Ib tumors have negative serum tumor markers whereas stage Is tumors are positive. These serum markers are also classified according to the degree of elevation of LDH, hCG, and AFP with S0 referring to normal markers, and S1, S2, and S3 are for increasing serum levels of these proteins. Regional nodes are staged both clinically and pathologically using size cutoffs of 2 and 5 cm. For clinical evaluation, regional nodes less than or equal to 2 cm are N1 disease, those greater than 2 cm but less than 5 cm are N2 disease, whereas nodes greater than 5 cm are N3 disease [1]. Pathologic assessment includes the number of positive nodes. Patients with stage II testicular cancer have retroperitoneal spread with stages IIa, IIb, and IIc having N1, N2, and N3 nodal disease, respectively. Distant metastases are stage III and are either M1a with nonregional (nonretroperitoneal) nodes or pulmonary spread, or M1b with nonpulmonary visceral metastases such as to the brain, bones, and liver. Staging of nodal and distant disease is typically performed with computed tomography (CT).

Highlights of testicular cancer staging | |

Regional nodes | N1: <2 cm; N2: >2, >5 cm; N3: >5 cm |

Stage I | Includes local T1-T4 disease. No nodal or distant metastases. |

Stage II | Retroperitoneal (regional) adenopathy, N1–N3. No distant metastases. |

Stage III | Nonregional nodes or other distant metastases |

T staging | |

T0 | No primary tumor (may have fibrosis in testis) |

T1 | Limited to testis and epididymis No vascular, lymphatic, or tunica vaginalis invasion |

T2 | Limited to testis and epididymis |

Vascular, lymphatic, or tunica vaginalis invasion may be present | |

T3 | Invasion of spermatic cord |

Vascular or lymphatic invasion may be present | |

T4 | Invasion of scrotum |

Vascular or lymphatic invasion may be present | |

N staging | |

N0 | No regional node metastases |

N1 | Metastases to <5 regional nodes; each node <2 cm |

N2 | Metastases to more than 5 regional nodes (each <5 cm) or nodes >2 and <5 cm |

N3 | Metastases to regional nodes >5 cm |

M staging | |

M0 | No distant metastases |

M1a | Metastases to nonregional nodes or lungs |

M1b | Metastases to other distant sites (besides nonregional nodes or lungs) |

Serum tumor marker staging | |

S0 | Normal markers |

S1 | LDH <1.5 times normal |

hCG <5,000 mIU/mL | |

AFP <1,000 ng/mL | |

S2 | LDH 1.5–10 times normal |

hCG 5,000–50,000 mIU/mL | |

AFP 1,000–10,000 ng/mL | |

S3 | LDH >10 times normal |

hCG >50,000 mIU/mL | |

AFP >10,000 ng/mL | |

Nodal Disease

Regional nodes for testicular cancer are in the retroperitoneum following the primary drainage pathway of each testis. These sites are precaval, paracaval, and interaortocaval nodes for right-sided testicular tumors, and paraaortic and preaortic nodes for left-sided tumors [1, 2]. Contralateral nodes are usually seen with large volume disease and right-sided tumors but are rare without ipsilateral adenopathy. Metastatic nodes are of soft tissue density or are heterogeneous with mixed solid and cystic components, the latter usually seen with nonseminomatous tumors. Progressive spread occurs to retrocrural, subcarinal, and supraclavicular nodes. Pelvic nodes can become enlarged secondary to lymphatic obstruction by bulky abdominal adenopathy [2]. Inguinal adenopathy can also occur when the primary tumor involves the scrotal wall. Although a short axis diameter of 10 mm is typically used to assess nodes, smaller nodes in expected sites of lymphatic drainage can harbor metastases [5].

The management of retroperitoneal nodes in early-stage testicular cancer differs for seminomatous and nonseminomatous tumors, both at initial presentation and after treatment (see Table 6.4). Retroperitoneal node dissection is not performed in early-stage seminoma but can be considered in nonseminomatous tumors. Seminoma is radiosensitive, unlike nonseminomatous tumors, and patients with clinical stage I disease may receive radiation to the retroperitoneum or surveillance for recurrence, which typically occurs at a median of 15 months in 15 % of patients [1]. For patients with nonseminomatous tumors, approximately 30 % of those with clinical stage I disease have occult nodal metastases, and options include retroperitoneal node dissection, chemotherapy, or surveillance for recurrence, which typically occurs in the first year [1, 2]. Node dissection is considered in particular for patients with risk factors such as lymphovascular invasion, embryonal carcinoma, or scrotal extension of tumor [1].

Table 6.4

Key differences between seminoma and nonseminomatous tumors

Seminoma | Nonseminomatous germ cell tumor (NSGCT) |

|---|---|

No elevation of serum AFP | Serum AFP can be elevated |

Surveillance or radiation for clinical stage I disease | Retroperitoneal node dissection, surveillance or chemotherapy for clinical stage I disease |

Teratomatous change rare | Teratomatous change seen in nodes after chemotherapy |

Resection considered for FDG avid residual retroperitoneal mass >3 cm | Residual retroperitoneal mass >1 cm resected regardless of activity on PET as teratoma is not FDG avid |

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection has been modified over time by limiting it to infrarenal nodes in low stage disease, as well as performing a unilateral dissection. The aim is to maximize the likelihood of resecting metastatic nodes while minimizing morbidity. If feasible, the sympathetic nerves are spared to preserve antegrade ejaculation. Based on studies mapping nodal stations, there are several side-specific templates for guiding dissection. For right-sided tumors, the precaval, paracaval, interaortocaval, and hilar gonadal vein nodes are resected and, in some templates, the preaortic and ipsilateral iliac nodes may also be included [6, 7]. For left-sided tumors, the preaortic, paraaortic, and hilar gonadal vein nodes are resected and the interaortocaval and ipsilateral iliac nodes may also be included depending on the template [6, 7].

Surveillance is included as a clinical option in patients with early-stage testicular cancer to avoid the complications of lymphadenectomy and the morbidity of radiation and chemotherapy, which carry the risk of long-term cardiovascular complications and second malignancy [8]. Patients are monitored by checking serum tumor markers, chest radiography or CT, and abdominal CT and this regimen is most intensive in the first year after treatment. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a nonradiation alternative to CT for surveillance of the retroperitoneum [9]. Chemotherapy is administered for advanced stages of both seminomatous and nonseminomatous tumors (see Table 6.5).

Table 6.5

Imaging evaluation of testicular cancer

Diagnosis | Primary modality: testicular ultrasound |

Problem solving: testicular MRI | |

Staging | Nodal or visceral metastases: CT chest, abdomen, pelvis |

Brain metastases in high-risk or symptomatic patients: CT brain | |

Brain or bone metastases: MRI | |

Post-treatment evaluation | Pulmonary recurrence: chest radiograph |

Abdominal recurrence in first 3 years: CT or MRI | |

Assessment for tumor in residual mass, or for evaluating patients with normal CT/MRI but elevated serum tumor markers: FDG-PET |

Once retroperitoneal nodes have been nonsurgically treated with radiation or chemotherapy, residual masses can be seen at imaging in up to 70 % of patients [10]. The majority of these masses in patients with seminoma consist of fibrotic tissue without active tumor or teratoma and are therefore observed [2]. Surgery is considered for masses larger than 3 cm with increased activity on positron emission tomography (PET) scans but complete resection can be challenging due to an appreciable desmoplastic reaction [1]. In contrast to seminoma, residual masses larger than 1 cm in patients with nonseminomatous tumors are resected as they have teratoma in 40 % of cases and viable tumor in 10 % [10]. Teratoma is seen either due to persistence of the original teratomatous component or due to transformation of the tumor with chemotherapy [3]. Change in the appearance of the mass to a simple-appearing cyst is seen with evolution to a differentiated mature teratoma. This is resected, as there is potential for growth with mass effect or malignant transformation in approximately 5 % of patients [1, 2, 8, 11]. A residual nodal mass with mixed solid and cystic appearance is also resected, as this can be seen with fibrosis, tumor, and/or necrosis. Increased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) activity in the residual mass on PET imaging suggests viable tumor [12, 13].

Other Metastases and Relapse

Although metastases from testicular tumors are typically by the lymphatic route, hematogenous spread can also occur. This is more common with nonseminomatous tumors and is seen in the lungs, liver, brain, and bones. Late relapse of testicular cancer is defined as a recurrence occurring more than 2 years after completing initial therapy. It occurs in 2–6 % of patients at a median interval of 6 years at sites such as the retroperitoneum, lungs, and mediastinum [1, 14]. Prognostic indicators for patients with germ cell tumors at presentation are serum tumor marker levels, primary tumor location, and visceral metastases. Seminoma patients without nonpulmonary visceral metastases are considered at good risk, regardless of the primary tumor site or serum tumor marker levels. However, seminoma patients with nonpulmonary metastases are at intermediate risk [1]. For patients with nonseminomatous tumors, the presence of a gonadal or retroperitoneal primary tumor, absence of nonpulmonary visceral metastases, and normal or stage 1 elevation of tumor markers are considered good risk features. Stage 2 serum tumor markers put the patient at intermediate risk and presence of a mediastinal primary tumor or nonpulmonary visceral metastases are poor risk factors.

Risk Factors for Testicular Cancer

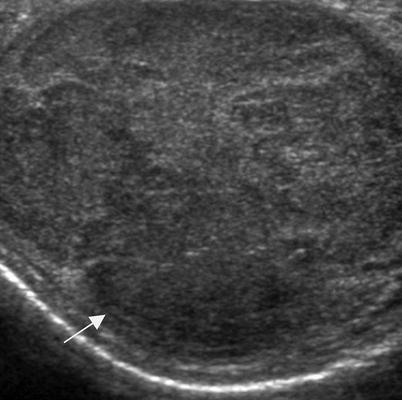

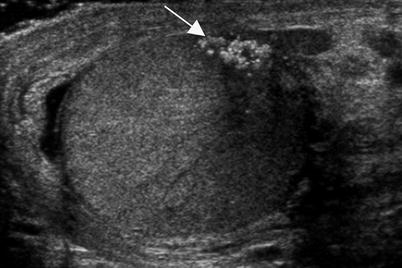

Fig. 6.1

Testicular atrophy. Ultrasound images of the scrotum in a 35-year-old man with right scrotal discomfort that was not alleviated by antibiotics. (a) Grayscale image of both testes shows asymmetry in testicular size with atrophy of the right testis (arrow). (b) Dedicated grayscale image of the right testis revealed a 5 mm hypoechoic mildly lobulated mass (arrow). The background parenchyma was mildly hypoechoic with scattered punctate calcifications. An atrophic testis is a risk factor for testicular cancer, rendering this lesion suspicious for malignancy. A 1 cm seminoma was diagnosed at orchiectomy

Fig. 6.2

Prior history of testicular cancer and testicular atrophy. Ultrasound images of the left testis from a patient with a history of right orchiectomy 12 years earlier for embryonal carcinoma and seminoma. (a) Grayscale image shows an atrophic left testis (arrow). Grayscale (b) and color Doppler (c) images reveal a well-circumscribed hypoechoic new lesion (arrow in b) in the left testis with peripheral vascularity. Pathology revealed a 2 cm mixed germ cell tumor composed of 65 % seminoma and 35 % embryonal carcinoma. This patient had two risk factors for testicular cancer: a prior personal history of testicular cancer and an atrophic remaining testis

Fig. 6.3

Prior history of testicular cancer. Axial CT images with intravenous contrast in a 40-year-old patient with a previous history of left orchiectomy and retroperitoneal radiation therapy for seminoma. Fourteen years later the patient presents with new right testicular enlargement and a heterogeneous testis on ultrasound. (a) CT image of the chest shows right hilar (arrow) and paraesophageal (arrowhead) adenopathy. The patient also had a history of sarcoidosis so biopsy was performed and revealed non-necrotizing epithelioid granulomata without malignancy. A right radical orchiectomy was subsequently performed and was positive for seminoma in the testis. The patient received chemotherapy as he had already received radiation to the retroperitoneum. A few months later the patient presented with back pain and (b) CT of the abdomen showed a retroperitoneal mass (arrow) encasing the right ureter. Biopsy of this mass was positive for metastatic seminoma and chemotherapy was given. (c) CT 3 months after chemotherapy shows the retroperitoneal mass (arrow) has decreased in size

Fig. 6.4

Undescended testis. Ultrasound images of the testis from a 25-year- old man with history of undescended testis and prior orchiopexy who now presented with vague scrotal swelling. Grayscale images of the left (a) and right (b) testes show a hypoechoic mass (arrow) in each testis and scattered punctate calcifications. The mass in the left testis is lobulated and larger. Color Doppler images of left (c) and right (d) testes show internal vascularity in the lesions, greater on the right. The patient’s serum tumor markers were normal. The patient desired intraoperative testicular biopsy prior to orchiectomy for positive biopsy. A left testicular biopsy followed by orchiectomy revealed a 0.9 cm mixed germ cell tumor, mainly embryonal subtype, with vascular invasion. A biopsy of the right testicular lesion revealed Leydig cell hyperplasia

Fig. 6.5

Undescended testis. MR and CT images of the pelvis in a 40-year-old patient who presented with a sensation of pressure in the suprapubic region. (a) Sagittal T2-weighted MR image of the pelvis shows a heterogeneous hyperintense mass (arrow) superior to the bladder (asterisk). Pre- (b) and post-contrast (c) T1-weighted coronal MR images of the pelvis show an enhancing soft tissue component in inferior aspect of mass (arrow) and necrosis (arrowhead) in the superior aspect of mass. Biopsy of the pelvic mass showed a poorly differentiated yolk sac tumor. Ultrasound (not shown) revealed a normal right testis but no convincing evidence of a left testis. Surgical exploration of the scrotum also did not reveal any left testicular tissue in the resected specimen. The patient was given chemotherapy and a follow-up CT was performed. (d) CT image of the upper pelvis shows a hypodense mass (arrows) in the midline. (e) A more inferior CT image shows the mass (arrow) is adjacent to the bladder (asterisk) and also has soft tissue (arrowhead) extending toward the left inguinal canal. (f) CT image of the lower pelvis shows absence of the left spermatic cord (arrow). A right spermatic cord is present (arrowhead). (g) CT at the level of the scrotum shows a solitary testis (arrow) with a small hydrocele. (h) Coronal CT reconstruction shows the mass (arrow), bladder (asterisk), and solitary testis (arrowhead) in the scrotum. The pelvic mass was resected after chemotherapy and consisted of testicular tissue with marked parenchymal atrophy and necrotic tissue without residual viable tumor

Fig. 6.6

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia. Ultrasound images of the scrotum from a 30-year-old man with a palpable left testicular mass. (a) Grayscale midline image shows asymmetric testicular size (arrow) with enlargement of the left testis. Grayscale (b) and color Doppler (c) images of the left testis show the parenchyma is replaced by multiple hypoechoic confluent nodules (arrow). Grayscale (d) and color Doppler (e) images of the right testis show two focal hypoechoic nodules (arrows) that are relatively well circumscribed. Bilateral orchiectomies revealed a 5.5 cm seminoma in the left testis and intratubular germ cell neoplasia. The right testicular parenchyma was atrophic with foci of intratubular germ cell neoplasia

Modes of Presentation of Testicular Cancer

Fig. 6.7

Palpable scrotal mass. A patient in his early twenties who presented with a palpable scrotal mass and weight loss. Grayscale ultrasound image of the left testis shows the testis is enlarged by a hypoechoic mass (arrow). Orchiectomy revealed seminoma. A palpable mass is a common presentation of testicular cancer

Fig. 6.8

Flank pain as presentation of stage II seminoma. A 35-year-old patient presented with flank pain and CT was performed to evaluate for renal stone. (a) Scans of the abdomen and pelvis showed no urinary tract calculi or hydronephrosis. However, retroperitoneal adenopathy is noted in the retrocaval (arrow) and left paraaortic regions (arrowhead). As the adenopathy is in the nodal drainage pathway of the testis, ultrasound was performed to evaluate for a possible testicular lesion as the primary source. (b) Grayscale ultrasound image of the right testis demonstrates a hypoechoic mass (arrow) replacing most of the parenchyma suspicious for malignancy. Biopsy of a retroperitoneal node revealed seminoma and the patient was treated with chemotherapy. (c) Grayscale ultrasound image of the right testis 3 months after chemotherapy shows decreased size of the testicular mass (arrow). The residual hypoechoic parenchyma demonstrated fibrosis at orchiectomy without viable tumor. Post-treatment fibrosis without viable tumor is a common pathologic finding in treated seminoma

Fig. 6.9

Abdominal pain as presentation of stage II seminoma. A 40-year-old male with history of inflammatory bowel disease presented with abdominal pain. (a) Axial CT image of the abdomen with oral and intravenous contrast CT showed a cystic thick-walled retroperitoneal mass (arrow). Biopsy of this mass revealed a necrotic, poorly differentiated neoplasm, possibly lymphoma, but the specimen was insufficient for further classification. A testicular ultrasound was performed as part of the workup of this retroperitoneal mass. Grayscale (b) and color (c) Doppler ultrasound images show a right testicular mass (arrow), which proved to be a seminoma with a hyalinized scar at orchiectomy and was compatible with a partially regressed germ cell tumor

Fig. 6.10

Chest pain as presentation of stage III seminoma. A 30-year-old patient presented with chest pain and CT was performed for evaluation. (a) Axial CT image of the chest with intravenous contrast demonstrates anterior mediastinal adenopathy (arrow) and a left pleural effusion (arrowhead). Soft tissue (b) and bone (c) windows of the lower chest revealed a mass in the left chest wall (arrow) with destruction of the adjacent rib. (d) Enlarged anterior diaphragmatic nodes (arrow) were also seen in the lower chest. Laboratory tests at the time of presentation also showed the patient to have jaundice. A staging CT of the abdomen (e) revealed a large peripancreatic mass (arrow). (f) The right hemiscrotum (arrow) was also noted to be enlarged and heterogeneous. Biopsy of the rib lesion was not definitive in characterizing the type of tumor so orchiectomy was performed and revealed seminoma

Testicular Masses on Ultrasound

Fig. 6.11

Seminoma. A 25-year-old patient presented with a palpable testicular mass. Grayscale (a) and color Doppler ultrasound (b) images of the left testis show a well-defined solid testicular mass (arrow) with some internal vascularity. Orchiectomy revealed a pure seminoma. Seminoma is typically a hypoechoic homogenous mass

Fig. 6.12

Embryonal cell carcinoma. A 30-year-old patient presented with testicular pain. Grayscale (a) and color Doppler ultrasound (b) images of the right testis show a homogeneous isoechoic mass (arrow) in the right testis with some internal vascularity. Orchiectomy revealed a pure embryonal cell carcinoma. Pure embryonal cell carcinoma is uncommon, occurring in approximately 3 % of cases. Embryonal carcinoma is usually an ill-defined hypoechoic mass that is typically part of a mixed germ cell tumor [4, 15]

Fig. 6.13

Embryonal cell carcinoma. A 20-year-old patient presented with a palpable testicular mass. Grayscale (a) and color Doppler ultrasound (b) images of the right testis show a hypoechoic mass (arrow in a) in the right testis with peripheral vascularity. Orchiectomy revealed a 1.4 cm embryonal cell carcinoma with vascular invasion

Fig. 6.14

Mixed germ cell tumor. A 20-year-old male presented with progressive back pain and emesis. The patient had enlarged retroperitoneal nodes on abdominal CT (not shown) and scrotal ultrasound was performed for further workup. Grayscale (a) and color Doppler ultrasound (b) images of the testis show a heterogeneous mixed solid and cystic mass (arrow in a) with internal vascularity. Pathologic examination of the orchiectomy specimen revealed a mixed germ cell tumor with a dominant embryonal carcinoma component, as well as smaller amounts of choriocarcinoma, yolk sac tumor, and mature teratoma. NGSCT are usually heterogeneous with cystic and echogenic components. The latter are due to calcification, fibrosis, or hemorrhage, whereas the former can be due to teratoma, necrosis, or dilated rete testes. Appreciable necrosis and hemorrhage can give choriocarcinoma the appearance of a mixed solid and cystic mass. Cystic regions are common in teratomas, which can also contain echogenic foci of bone and cartilage [4, 15]

Fig. 6.15

Burned-out testicular tumor in a teenager who presented with flank pain and fatigue. The patient had retroperitoneal adenopathy on CT (not shown) and an elevated serum hCG level. Scrotal ultrasound was performed. A grayscale ultrasound image of the left testis demonstrated a cluster of coarse calcifications (arrow) without a discrete hypoechoic mass. Shadowing is evident from the calcifications. Calcified scar without viable tumor was seen at orchiectomy and findings were consistent with a regressed or burned-out tumor. Burned-out tumor occurs when the mass outgrows its blood supply and infarcts with resultant fibrosis. The residual mass in the testis can appear as echogenic foci or a small hypoechoic mass [4, 15]

Fig. 6.16

Burned-out testicular tumor. A 50-year-old patient with a history of seminoma in the right testis 30 years earlier presented with abdominal pain and weight loss. (a) Axial CT image of the abdomen with oral and intravenous contrast showed retroperitoneal adenopathy (arrows) and biopsy revealed seminoma. (b) Grayscale ultrasound image of the left testis showed hypoechoic masses (arrow) with punctate calcifications. There was extensive scarring with hyalinization and focal microcalcification at orchiectomy consistent with a burned-out lesion

Fig. 6.17

Burned out testicular tumor. A 40-year-old man presented with back pain and had a large retroperitoneal mass on MRI of the spine (not shown). A biopsy of this mass revealed a poorly differentiated germ cell tumor and a testicular ultrasound was performed. Grayscale ultrasound image demonstrates a small hypoechoic well-defined testicular mass (arrow). Orchiectomy revealed intratubular germ cell neoplasia and scarring possibly due to regression of an invasive germ cell tumor

Fig. 6.18

Leukemic infiltration of the testis. A teenager with a recent systemic relapse of leukemia presented with an enlarged left testis. (a) Grayscale ultrasound image of both testes shows asymmetric testicular size with enlargement of the left testis (arrow). Grayscale images of the left testis (b) and left epididymis (c) show hypoechoic tissue infiltrating the testis (arrow) and enlarging the epididymis (arrowhead). (d, e) Follow-up ultrasound 2 weeks after chemotherapy showed significant improvement in the left testis. (d) Color Doppler image of the testis shows normal echogenicity of the parenchyma except for a small residual hypoechoic area around the mediastinum testis (arrow) consistent with resolving leukemic infiltration. (e) Grayscale image shows decreased swelling of the left epididymis (arrowhead) and normal contour of the testis

Fig. 6.19

Primary testicular lymphoma. A 60-year-old man presented with painless right testicular swelling and a palpable mass. Grayscale (a) and color Doppler ultrasound (b) images of both testes show asymmetric enlargement of the right testis (arrow in a), which is diffusely heterogeneous and has increased vascularity. Orchiectomy revealed a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. There was no systemic adenopathy. Testicular lymphoma is invariably B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Single or multiple hypoechoic homogenous masses are typically present. The testis is enlarged and tumor can also infiltrate the epididymis. The tumor has increased vascularity on color Doppler ultrasound [4, 15]

Fig. 6.20

Lymphoma relapse in testis. A 60-year-old patient with a history of treated primary central nervous system lymphoma now presents with an enlarged painless right testis. (a) Grayscale ultrasound image of both testes shows an asymmetrically enlarged right testis (arrow). Grayscale (b) and color Doppler (c) images of the right testis (arrow in b) show it is diffusely hypoechoic with increased vascularity. Infiltrating hypoechoic tumor is also seen in the right epididymis (arrowhead in b). (d) Axial image from a PET scan performed for staging demonstrated a hypermetabolic right testicular mass (arrow) with no evidence of recurrent hypermetabolic tumor in the brain or lymph nodes. Orchiectomy revealed a diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the testis and epididymis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree