6 The abdomen and bowel

Embryology

The primordial gut is divided into three parts: the foregut, midgut and hindgut.

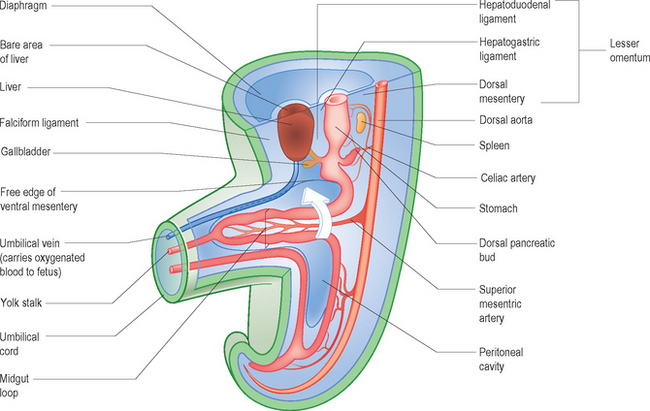

The midgut forms the duodenum beyond the sphincter of Oddi (where the common bile duct enters the duodenum), the jejunum, the ileum, the cecum, the appendix and the ascending and right two thirds of the transverse colon. Due to the rapidly enlarging liver and two sets of kidneys within the abdomen there is a shortage of space within the abdominal cavity. The primitive midgut forms a loop, the midgut loop, the apex of which is continuous with the vitello-intestinal duct or yolk stalk. The midgut loop elongates rapidly on an elongated dorsal mesentery which is extruded into the extra-embryonic coelom at the umbilicus. This extrusion constitutes the physiological umbilical hernia. The major artery supplying the midgut is the superior mesenteric artery, which is central to this whole process of herniation and rotation (Fig. 6.1).

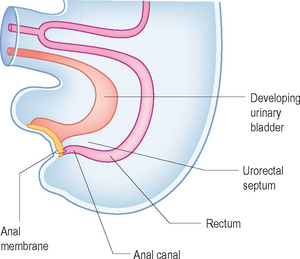

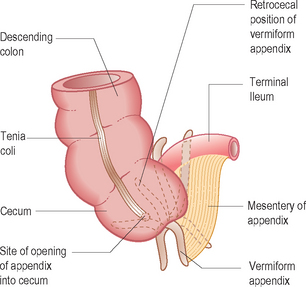

Since the appendix develops during the descent of the colon, its final position frequently is posterior to the cecum or colon. These positions of the appendix are called retrocecal or retrocolic (Fig. 6.2).

Figure 6.2 Position of a retrocecal appendix. These can be very difficult to identify on ultrasound.

The hindgut forms the left third of the transverse colon, the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, the rectum and the upper part of the anal canal. The urogenital organs are separated from the primitive rectum by the urorectal septum (Fig. 6.3). The anorectal anomalies occur when there is abnormal separation of the rectum from the urogenital system by arrested growth or deviation of the septum. This results in atresia of the rectum and fistulas to the urethra, bladder or vagina. High anorectal atresias are all associated with a fistula. In addition the development of the rectum and urogenital system takes place at the same time as that of the spine, and hence there is a high association with spinal anomalies.

ABNORMALITIES RELATED TO EMBRYOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT

ULTRASOUND TECHNIQUE

ABNORMALITIES OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Gastroesophageal reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the retrograde flow of milk and solids from the stomach up the esophagus. This is particularly common in infants, where they may present with persistent vomiting and failure to thrive, but the important association in terms of the use of ultrasound is with gastric outflow obstructions such as pyloric stenosis and malrotation. It is recognized that ultrasound can detect GER (although it is not widely employed, as it is time consuming) with just a short snapshot view of the gastroesophageal junction. However, there are better, more sensitive tests available. The ‘gold standard’ test is a pH study where a probe is placed in the lower esophagus and monitored over a 24-hour period for acidity within the esophagus. Also a radioisotope milk scan may be used, where the baby is given milk containing tracer and then scanned for GER and even sometimes aspiration of tracer into the lungs. A conventional barium meal is probably still the examination most widely used, because of cost and availability, and it has the added advantage over all other tests of being able to demonstrate the anatomy of the gastric outlet.1

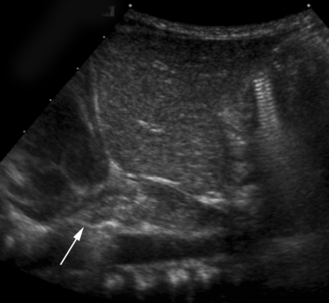

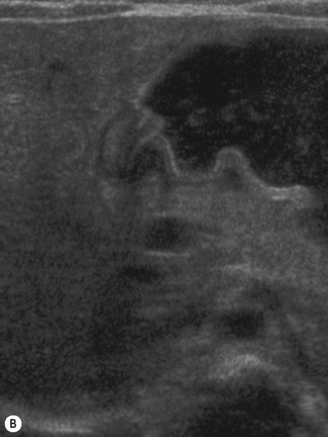

The ultrasound technique involves giving the baby a liquid feed prior to the examination and laying the infant supine. In the supine position the gastric fundus is filled, so this is the optimal sonographic positioning. Reflux will only be observed effectively on ultrasound if the stomach is filled with clear fluid or milk. The gastroesophageal junction lies just to the left of the aorta, in the region of the xiphisternum, and can be seen by scanning longitudinally over the upper abdominal aorta. By slightly angling the transducer to the left of the aorta the gastroesophageal junction and lower esophagus come into view. If GER is present, then air and gastric contents can be seen to reflux up the esophagus (Fig. 6.4). GER is common and probably physiological in most infants. It can cause major problems, however, when it is associated with hiatus hernia, severe vomiting and failure to thrive together with aspiration causing cyanotic spells and chronic lung disease.

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis

Pyloric stenosis is an evolving condition of progressive pyloric muscle hypertrophy, which then narrows and elongates the pyloric canal. It typically occurs in male newborn infants at approximately 6 weeks and is familial. Infants present with projectile vomiting, and an epigastric mass feeling like an olive or walnut can be palpated in the majority of patients. Sometimes marked gastric peristalsis can be seen visibly on the abdominal wall. In clinically obvious cases ultrasound or barium examinations are generally not necessary. It is in the more difficult equivocal cases, where no mass can be palpated, that imaging is requested.2–12

Technique of ultrasound examination

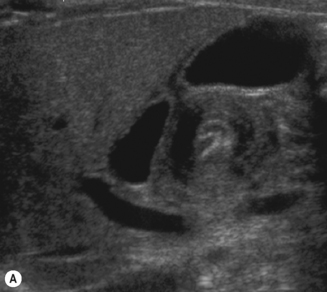

The baby may have a nasogastric tube draining the stomach, or have been vomiting severely, in which case the stomach will be empty. It is useful to be able to give the baby clear fluid, and this can be done via the nasogastric tube or with a bottle. The clear fluid will fill the gastric antrum so that it can be used as an acoustic window for the pylorus. Secondly, an assessment can be made of whether any fluid is passing through the pylorus into the duodenum. Normally fluid can be seen to pass through the pylorus and into the duodenum without delay (Fig. 6.5).

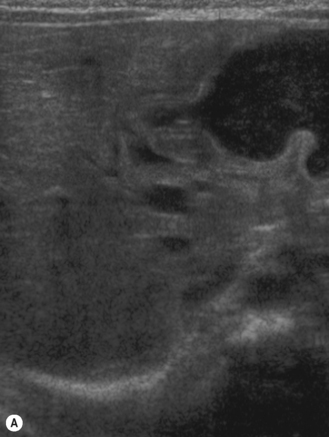

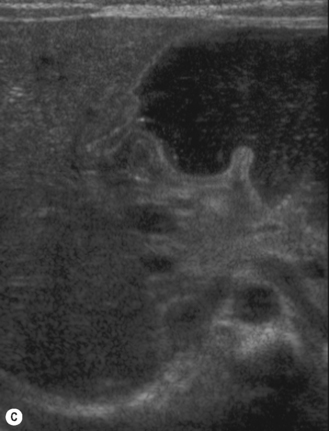

Start by scanning longitudinally in the right upper quadrant just medial to the gallbladder. Once the ‘doughnut’ of the transverse section through the hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is identified, pivot on the axis through 90° to get the longitudinal measurement. The trick in the transverse view is to identify the gastric antrum and, if the abdomen is too gassy, turn the infant right side down in order to displace gas and fill the antrum with fluid. The appearances to look for are the hypoechoic thickening of the pyloric muscle and elongation of the canal. Table 6.1 gives the published data for measurements of the canal in different series. Virtually no authors are in entire agreement, which makes remembering the measurements even more difficult! Broadly speaking, keep in mind 10 mm × 15 mm, i.e. take a pyloric length of over 15 mm and an overall width of 10 mm as abnormal in an average weight for term baby. These measurements are a slight overestimation but easily remembered. In the many series in the literature there is an overlap in measurements between the normal and abnormal pylorus. To the experienced eye, if the pylorus is abnormal it is easy to identify, often without any measurements at all (Fig. 6.6).

Table 6.1 Sonographic measurements of pyloric stenosis

| Reference | Year | Measurements |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1988 | Muscle thickness 4.8 ± 0.6 mm Canal length 21 ± 3 mm |

| 8 | 1994 | Muscle thickness 4–4.4 mm Canal length 11–15 mm |

| 10 | 1998 | Muscle thickness > 3 mm Canal length > 15 mm Pyloric diameter > 11 mm Pyloric volume > 12 ml |

Stomach conditions

Thickening of the gastric mucosa or all of the stomach may be seen in a number of conditions. Lymphoma with infiltration of the bowel wall, while rare, is probably the commonest infiltrative disorder seen. Other causes such as chronic granulomatous disease (Fig. 6.7), and rarely Henoch–Schönlein purpura, and Crohn disease may also cause thickening of the gastric wall.

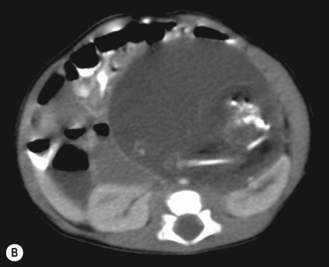

Tumors of the stomach are also extremely rare, and the commonest tumor seen in the pediatric age group is the teratodermoid (Fig. 6.8). These teratodermoids appear the same as dermoids elsewhere in the abdomen and typically have a mixed echogenic appearance often containing fat, teeth and hair. Ectopic pancreatic tissue can also occur in the region of the antrum of the stomach and may be responsible for gastric outlet obstruction. Typically the pancreatic tissue lies in the wall of the stomach and produces a polypoid outpouching that may be responsible for gastric outlet obstruction (see Fig 5.26). It may also cause gastric bleeding.

Malrotation

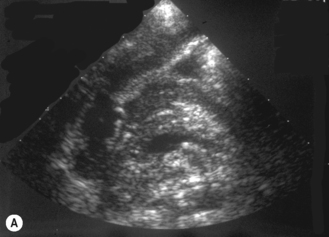

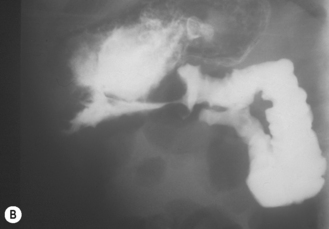

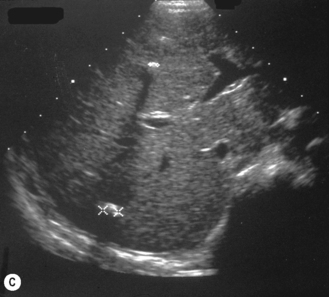

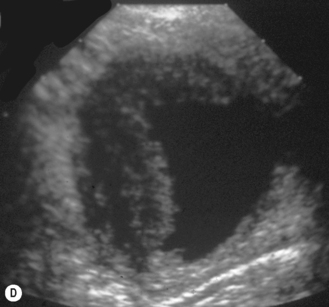

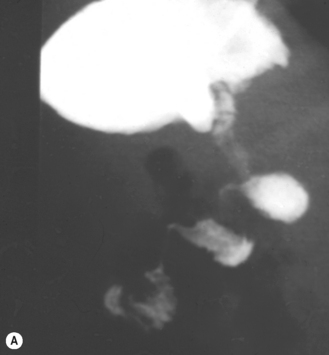

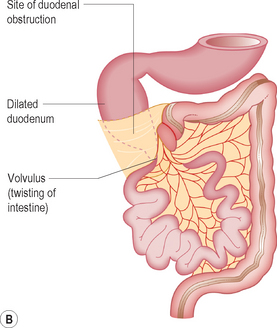

Malrotation of the bowel occurs as a result of the abnormal positioning of the bowel in embryological life. The clinical history par excellence that should alert the sonographer to the diagnosis is bilious vomiting. The vomit is bilious because the obstruction is distal to the entry of the bile duct at the sphincter of Oddi. Typically this occurs in the neonatal period, and on plain film radiography the abdomen is described as being gasless with just a distended stomach and second part of the duodenum. Malrotation may occur on its own, in which case the sonographer should concentrate efforts on the orientation of the superior mesenteric artery and vein. When it is complicated by volvulus (i.e. twisting on the short mesentery around the superior mesenteric artery), ultrasound may show the so-called whirlpool sign which corresponds to the twisted ribbon on barium studies (Fig. 6.9). Malrotation complicated by volvulus is one of the pediatric surgical emergencies as the whole of the midgut may infarct as the bowel twists around and obstructs the blood flow in the superior mesenteric artery.13–17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree