4 The adrenal glands

NORMAL APPEARANCES AND ULTRASOUND TECHNIQUE

Normal appearances

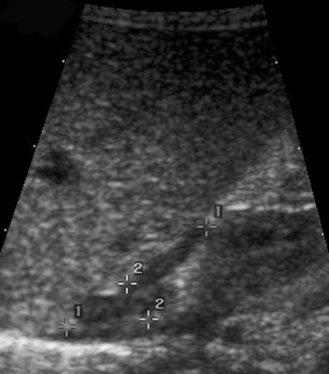

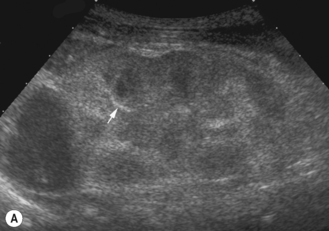

The adrenal glands lie above the kidneys in an anteromedial position. They have a typical wishbone appearance and form a cap or an inverted V over the kidneys. They are most easily seen at birth and in the neonate until about 1 month, when they are large and have a typical hypoechoic cortex and hyperechoic medulla (Fig. 4.1). They lose about a third of their weight during the first 4 weeks of life, because of the regression of the primitive fetal cortex. They continue to regress and do not regain their original weight till about the end of the second year of life. After the early neonatal period the gland appears essentially very similar to that seen in the adult.1

Size

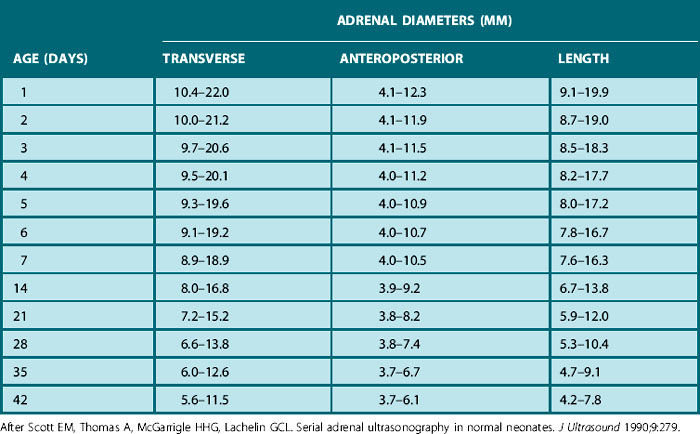

Normal measurements are quoted in the literature for the pediatric adrenal gland and are included here for completeness (Table 4.1). In reality these measurements are of little use clinically and are not routinely used in clinical practice.

Ultrasound technique

The right adrenal

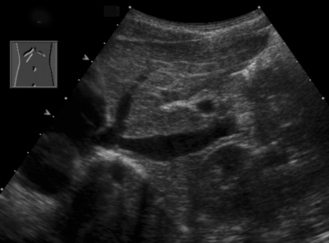

There are two ways to visualize the right adrenal in a child:

• Start off conventionally in the right flank using the liver as an acoustic window. Identify the right kidney and then angle medially to locate the area between the right crus of the diaphragm and IVC.

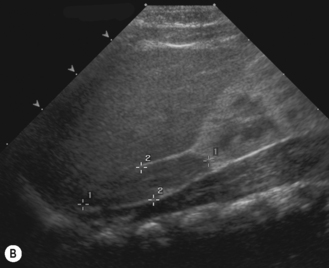

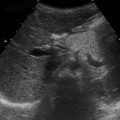

• Alternatively, start scanning longitudinally over the IVC. Gradually rotate the transducer 45° to the right so that an image of the upper IVC and right upper pole of the kidney is obtained. The adrenal lies in the angle between these two structures (Fig. 4.2).

ABNORMALITIES OF THE ADRENAL GLANDS

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)

This is a recessively inherited condition caused by an enzyme deficiency in the adrenal cortex. In the majority of patients the deficient enzyme is 21-hydroxylase. Clinically there is an accumulation of steroidal precursors proximal to the enzyme deficiency, with a resulting diversion into the androgen (therefore male) biosynthesis pathways. This results in virilization of females and early masculinization in males. In the majority, aldosterone cannot be synthesized, and some infants may present with severe salt wasting in the neonatal period which may be fatal. While the adrenal glands may be detectably enlarged in some, ultrasound plays little role in assessing the glands.2 However, CAH is the most common cause of female pseudohermaphroditism, with female infants presenting with ambiguous genitalia. The role of ultrasound in these infants with ambiguous genitalia is to demonstrate the presence of internal female structures (uterus and ovaries). The uterus is occasionally associated with a small hydrometrocolpos, as the insertion of a vagina may be anomalous and narrowed, sometimes inserting into the urethra with a persistent urogenital sinus3–5 (see Fig. 7.11).

Adrenal hemorrhage

Adrenal hemorrhage is a common cause of an abdominal mass in a neonate. This has been reported in the literature as sometimes occurring as an antenatal event, and the sonographic appearances postnatally often confirm this. Conditions which are associated with adrenal hemorrhage are hemoconcentration caused by shock, hypoxia, septicemia, birth trauma or stress, and this occurs particularly in infants of diabetic mothers.6,7

There is a common association with renal vein thrombosis, which must be actively excluded, and this is more commonly left sided because of the insertion of the left adrenal vein into the left renal vein. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhages can occur. Hemorrhages may be complicated by abscess formation.8

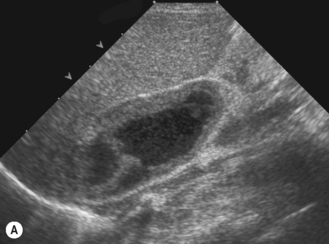

Ultrasound appearances

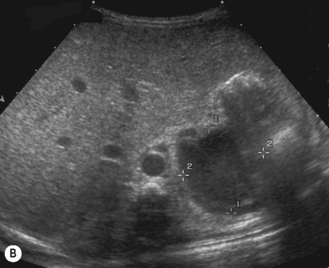

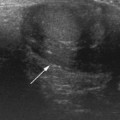

The adrenal hemorrhage has differing appearances depending on when in the evolution of the hemorrhage the ultrasound examination is performed. In the early stages when there is fresh hemorrhage, the adrenal is enlarged and echogenic. As the blood starts to liquefy, the central area becomes increasingly hypoechoic with some internal echoes; this can take 1–2 weeks from the time of hemorrhage. In a short space of time the hemorrhage starts shrinking (Fig. 4.3) and may ultimately be left with a rim of calcification. On plain abdominal radiography this is typically triangular in shape.

When an adrenal hemorrhage is found, the kidneys must be carefully scanned and measured and the echogenicity evaluated for renal vein thrombosis. The features to look for are an echogenic enlarged swollen kidney with the typical increase in echogenicity of the interlobular vessels (Fig. 4.4).9

A much rarer condition, neuroblastoma, is the main differential diagnosis. Normally a neuroblastoma is more solid in appearance and will not change its internal echo texture with time. Serial examination is therefore recommended in the uncertain cases. However, urinary catecholamines (VMAs) will be elevated in over 90% of patients with neuroblastoma. Neuroblastoma may also undergo hemorrhage and be cystic in appearance.10 This coexistence with neuroblastoma may require further cross-sectional imaging, and it is in these instances that an MRI scan may improve diagnostic accuracy. Sonography, however, remains the prime imaging modality of choice.

Adrenal cystic lesions

Cystic adrenal masses are rare, but there are some conditions in which lesions may appear cystic:

• A resolving adrenal hemorrhage may appear complex, with internal echoes, and is usually seen after 2–3 weeks.

• Cystic neuroblastoma is very rare.

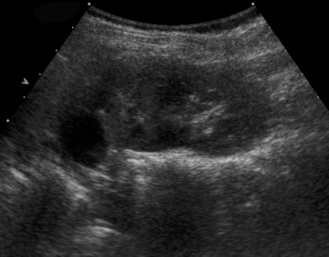

• True adrenal cysts are very rare and appear purely cystic with a thin wall and no internal echoes. They may be associated with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome (Fig. 4.5).

• Lesions that may mimic an adrenal cyst are an obstructed upper moiety of a renal duplex system or a localized upper moiety multicystic kidney. An MCU may help by showing reflux into the lower moiety and an ‘incomplete’ kidney.