Cerebral Hemispheres

The cerebral hemispheres fill the cranial vault above the tentorium cerebelli. Right and left hemispheres are partly separated by the interhemispheric fissure. There are several white matter tracts connecting both hemispheres, the largest of which is the corpus callosum. The hemispheres consist of cortical grey matter, white matter, basal ganglia, thalamus, hypothalamus, pituitary gland and the limbic lobe. The lateral ventricles form a cavity within each hemisphere.

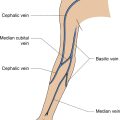

Cerebral Cortex ( Figs. 2.1, 2.2 )

The cerebral cortex is the superficial grey matter and is composed of neuronal cell bodies. There are four main subdivisions – the frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobes – which are delineated by sulci in the cortex. The superolateral surface of each cerebral hemisphere has two deep sulci; these are:

- ■

The lateral sulcus , also known as the Sylvian fissure, which separates the frontal and temporal lobes.

- ■

The central sulcus (of Rolando), which passes upwards from the lateral sulcus to the superior border of the hemisphere. This separates the frontal and parietal lobes.

- 1.

Central sulcus

- 2.

Parieto-occipital sulcus

- 3.

Insula

- 4.

Temporal horn of lateral ventricle and hippocampus

- 1.

Cingulate gyrus

- 2.

Central sulcus

- 3.

Parieto-occipital sulcus

- 4.

Corpus callosum

- 5.

Fornix

The parieto-occipital sulcus on the medial surface of the hemisphere separates the parietal and occipital lobes. On the lateral surface of the hemispheres there is no complete sulcal separation of the parietal, temporal and occipital lobes. The boundary between the parietal and temporal lobes lies on a line extended back from the lateral sulcus. The boundary separating the parietal and temporal lobes from the occipital lobe is a line between the superior border of the parieto-occipital sulcus and the preoccipital notch (see Fig. 2.1 ).

Cortical regions within each lobe control different functions, some of which have been identified to date.

FRONTAL LOBE

The frontal lobe includes all of the cortex anterior to the central sulcus and superior to the lateral sulcus. The frontal cortex contains four main gyri, the precentral gyrus and the superior, middle and inferior frontal gyri. The motor cortex, premotor cortex and prefrontal area are some of the regions associated with known major functions.

Primary Motor Cortex

The motor cortex is centred on the precentral gyrus, which is immediately anterior to the central sulcus. It controls voluntary movement. Specific regions of the motor cortex control specific and predictable body parts. This can be displayed diagrammatically as the ‘human homunculus’. The corticospinal and corticobulbar motor tracts emanate from the primary motor cortex.

Premotor Cortex

The premotor cortex is the anterior part of the precentral gyrus and adjoining gyri. Its function is less well understood but it is also associated with the control of voluntary movement. The posteroinferior part of the premotor area, on the inferior portion of the inferior frontal gyrus on the dominant hemisphere, is Broca’s area , which is responsible for the production of speech.

Prefrontal Area

Anterior to the motor and premotor cortex, the frontal lobes are involved with intellectual, emotional and autonomic activity. On the medial surface of the frontal lobe, above and parallel to the corpus callosum, is the callosal sulcus. Above this, the cingulate gyrus extends posteriorly from the frontal lobe into the parietal lobe. This, in turn, is separated superiorly from the remainder of the medial surface by the cingulate sulcus.

PARIETAL LOBE

The parietal lobe is posterior to the central sulcus and superior to the lateral sulcus and a line drawn from its posterior end to the occipital lobe (see Fig. 2.1 ). Areas with known function include the primary somatosensory cortex and the parietal association cortex.

Primary Somatosensory Cortex

This is found on the gyrus posterior to the central sulcus and is known as the postcentral gyrus. This controls somatic sensations.

Parietal Association Cortex

This is posterior to the sensory cortex. This area is involved with recognition and integration of sensory stimuli.

TEMPORAL LOBE

The temporal lobe lies inferior to the lateral sulcus and anterior to the occipital lobe. Two horizontal gyri separate the superolateral surface into superior, middle and inferior temporal gyri. Areas associated with known function include the primary auditory cortex and the temporal association cortex.

Primary Auditory Cortex

Found on the superior temporal gyrus, the auditory cortex’s function is the reception of auditory stimuli. Wernicke’s area , responsible for the interpretation of language, is located within the superior temporal gyrus, most commonly in the dominant lobe.

Temporal Association Cortex

Situated around the auditory cortex, this area is involved with the recognition and integration of auditory stimuli.

OCCIPITAL LOBE

The occipital lobe lies posterior to the parietal and temporal lobes. There is no anatomical separation of these lobes on the superolateral surface of the hemisphere. However, on the medial surface, the occipital lobe is separated from the parietal lobe by the parieto-occipital sulcus. A further deep sulcus of this surface, the calcarine sulcus, runs anteriorly from the occipital pole (see Fig. 2.2 ). Areas with known function include the primary visual cortex and the occipital association cortex.

Primary Visual Cortex

This surrounds the calcarine sulcus and receives visual stimuli from the opposite half field of sight.

Occipital Association Cortex

This lies anterior to the visual cortex and is involved with the recognition and integration of visual stimuli.

INSULA (OF REIL)

This is the cortex buried in the floor of the lateral sulcus and is crossed by branches of the middle cerebral artery. Its function is not fully understood; however, it has multiple connections to each of the major lobes as well as the limbic system and basal ganglia. Gustatory and sensorimotor processing are some of its better understood roles, although the area closest to the sensory cortex is probably related to taste. The parts of the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes that overlie the insula are called the operculum. The extreme capsule, claustrum and external capsule lie increasingly medial to the insula ( Fig. 2.7 ).

RADIOLOGICAL FEATURES OF THE CEREBRAL CORTEX

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Identification of lobes on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) slices depends on identification of their boundaries. The advent of high-resolution volumetric imaging of the brain with multiplanar reformatting for both CT and MRI have facilitated identification of the major fissures. The sylvian cistern and fissure separating the frontal and temporal lobes are easily identified on axial CT or MR slices ( Fig. 2.3 ). The central sulcus that forms a boundary between the frontal and parietal lobes can be more difficult to identify, however. Because CT images are obtained parallel to the canthomeatal line, on upper images the central sulcus is quite posterior in position. This lies at a transverse level just posterior to the anterior limit of the lateral ventricles.

- 1.

Ethmoid sinus

- 2.

Globe

- 3.

Right temporal lobe

- 4.

Pons

- 5.

Fourth ventricle

- 6.

Right cerebellar hemisphere

- 7.

Petrous part of temporal bone

- 8.

Basilar artery

- 9.

Middle cerebellar peduncle

- 10.

Superior cerebellar peduncle

- 11.

Fifth cranial nerve

- 12.

cavernous sinus

- 1.

Crus of midbrain

- 2.

Aqueduct of Sylvius

- 3.

Interhemispheric fissure

- 4.

Gyrus rectus

- 5.

Sylvian fissure

- 6.

Optic chiasm

- 7.

Mamillary body

- 8.

Vermis of the cerebellum

- 9.

Ambient cistern

- 10.

Quadrigeminal plate

- 11.

Left occipital lobe

- 12.

Middle cerebral artery

- 1.

Interhemispheric fissure

- 2.

Tapetum

- 3.

Genu of corpus callosum

- 4.

Head of caudate nucleus

- 5.

Anterior horn of right lateral ventricle

- 6.

Interventricular foramen

- 7.

Sylvian fissure

- 8.

External capsule

- 9.

Anterior limb of internal capsule

- 10.

Putamen of lentiform nucleus

- 11.

Globus pallidus of lentiform nucleus

- 12.

Posterior limb of internal capsule

- 13.

Thalamus

- 14.

Atrium and choroid plexus of lateral ventricle

- 15.

Calcarine sulcus

- 16.

Superior sagittal sinus

- 17.

Septum pellucidum

- 18.

Claustrum

- 19.

Splenium of corpus callosum

- 1.

Central sulcus – note characteristic inverted omega shape on left side

- 2.

Precentral gyrus

- 3.

Post central gyrus

- 4.

Superior frontal gyrus

There are a number of landmarks and signs that have been described to facilitate identification of the central sulcus. For example, on axial images the central sulcus has been described as having an inverted omega-shaped curve that marks the position of the hand motor cortex (see Fig. 2.3D ). Also on axial imaging, the L-sign describes the junction of the superior frontal gyrus and precentral gyrus with the central sulcus lying posterior to this. The T-sign is the sulcal equivalent of this, with the superior frontal sulcus and precentral sulcus meeting intersecting as a T-shape (see Fig. 2.3E ). The central sulcus is the sulcus posterior to this. Additionally the cortex of the precentral gyrus is thicker than that of the post central gyrus (see Fig. 2.3D ).

The parieto-occipital sulcus on the medial surface of the hemisphere can be seen on CT at the level of the lateral ventricles and on midline sagittal MRIs (see later Fig. 2.5 ). The parieto-occipital junction on the lateral surface has no anatomical landmark but lies at approximately the same transverse level as the sulcus.

Midline sagittal images also show the cingulate gyrus and callosal and cingulate sulci. The insula and the frontal, parietal and temporal opercula can be seen on axial CT and on MRI in all planes.

In adults the white matter is myelinated. In this setting, grey matter is T2 hyperintense and T1 hypointense relative to white matter.

On an unenhanced CT the grey matter is relatively hypodense compared to the white matter.

ULTRASOUND EXAMINATION OF THE NEONATAL BRAIN

The intracranial structures are amenable to ultrasound-guided assessment in neonates and infants while the anterior fontanelle is open. This is the first-line evaluation for most neonates requiring neuroimaging and can be performed at the bedside.

Sulci and gyri can be identified including the interhemispheric fissure, the lateral sulcus, insula and operculum on coronal images, and the corpus callosum and cingulate gyri on midline sagittal views (see later Fig. 2.10 ).

The medial wall of the atrium of the lateral ventricle is indented by the white matter over the calcarine sulcus, the calcar avis. In parasagittal views on cranial ultrasound of the newborn, this can be mistaken for thrombus in the ventricle, but imaging in the coronal plane confirms its continuity with normal parenchyma.

White Matter of the Hemispheres

White matter is primarily composed of myelinated axons and supporting glial cells. White matter forms fibre tracts which relay information and help coordinate actions between different parts of the brain and spine.

There are three main types of fibre within the cerebral hemispheres:

- ■

Commissural fibres, which connect corresponding areas of the two hemispheres.

- ■

Association (arcuate) fibres, which connect different parts of the cortex of the same hemisphere.

- ■

Projection fibres, which join the cortex to lower centres.

COMMISSURAL FIBRES

The Corpus Callosum ( Figs. 2.4, 2.5 )

The corpus callosum is a large midline mass of commissural fibres, each of which connects corresponding areas of both hemispheres. It is approximately 10 cm long and becomes progressively thicker towards its posterior end. Named parts include the following:

- ■

Rostrum – this is the first part, which extends anteriorly from the anterior commissure (see below).

- ■

Genu – this is the most anterior part where it bends sharply backwards.

- ■

Trunk (body) – this is the main mass of fibres extending from the genu anteriorly to the splenium posteriorly. It lies below the lower free edge of the falx cerebri. Branches of the anterior cerebral vessels run on its superior surface.

- ■

Splenium – this is the thickened posterior end.

- 1.

Frontal lobe

- 2.

Parietal lobe

- 3.

Occipital lobe

- 4.

Rostrum of corpus callosum

- 5.

Genu of corpus callosum

- 6.

Body of corpus callosum

- 7.

Splenium of corpus callosum

- 8.

Septum pellucidum

- 9.

Foramen of Monro

- 10.

Fornix

- 11.

Massa intermedia of thalami

- 12.

Third ventricle

- 13.

Supraoptic recess of third ventricle

- 14.

Suprapineal recess of third ventricle

- 15.

Pineal gland

- 16.

Optic chiasm

- 17.

Midbrain

- 18.

Interpeduncular cistern

- 19.

Aqueduct of Sylvius

- 20.

Quadrigeminal plate (superior and inferior colliculi)

- 21.

Quadrigeminal plate cistern

- 22.

Fourth ventricle

- 23.

Vermis of cerebellum

- 24.

Pons

- 25.

Tonsil of cerebellum

- 26.

Prepontine cistern

- 27.

Medulla oblongata

- 28.

Odontoid process

- 29.

Cisterna magna

- 30.

Clivus

- 31.

Pituitary

- 32.

Mamillary body

- 33.

Tentorium cerebelli

- 34.

Spinal cord

- 35.

Sphenoid sinus

In cross-section, fibres from the genu that arch forward to the frontal cortex on each side are called forceps minor and fibres from the splenium passing posteriorly to each occipital cortex are called forceps major . Fibres extending laterally from the body of the corpus callosum are called the tapetum . These form part of the roof and lateral wall of the lateral ventricles.

Anterior Commissure ( Figs. 2.4, 2.6 )

This is a bundle of fibres in the lamina terminalis in the anterior wall of the third ventricle. The fibres pass laterally in an arc, indenting the inferior surface of the globus pallidus. The anterior commissure runs anterior to the anterior columns of the fornix and caudal to the anterior limb of the internal capsule. The anterior commissure is part of the olfactory system and connects the olfactory bulbs, the cortex of the anterior perforated substance and the piriform areas.

- 1.

Anterior commissure

- 1.

Anterior commissure

- 2.

Corpus callosum

- 3.

Head of caudate nucleus

- 4.

Internal capsule

- 5.

Putamen

- 6.

External capsule

- 7.

Claustrum

- 8.

Insula

- 1.

Corpus callosum

- 2.

Fornix

- 3.

Anterior commissure

- 4.

Mamillary body

- 5.

Posterior commissure

- 6.

Pineal gland

- 7.

Quadrigeminal plate

- 8.

Quadrigeminal plate cistern

- 9.

Habenular commissure

Habenular Commissure

This small commissure is situated above and anterior to the pineal body. It unites the habenular striae, which are fibres from the olfactory centre that pass posteriorly along the upper surface of each thalamus and unite in a ‘U’ configuration in this commissure.

Posterior Commissure

This is situated anterior and inferior to the pineal body. It lies dorsal to the cerebral aqueduct and forms part of the posterior wall of the third ventricle. It connects the superior colliculi, which are concerned with light reflexes (see brainstem).

Hippocampal Commissure

This is the commissure of the fornix (see below) and connects the two hippocampi. It lies below the body and splenium of the corpus callosum and is in close proximity to the Foramen of Monroe.

PROJECTION FIBRES

These fibres join the cerebral cortex to lower centres in the deep nuclei, cerebellum, brainstem and spinal cord. Some fibres are afferent and some efferent. A number of major projection fibres converge together to form the internal capsule, where they lie lateral to the thalamus and the corona radiata as they fan out between the internal capsule and the cerebral cortex.

Internal Capsule (see Fig. 2.3C )

This contains sensory fibres from the thalamus to the sensory cortex and motor fibres from the motor cortex to motor nuclei in the brainstem, corticobulbar tracts and, in the spinal cord, the corticospinal (pyramidal) tracts. These tracts occupy predictable locations within the internal capsule.

In axial cross-section, the internal capsule has an anterior limb between the caudate and lentiform nuclei and a posterior limb between the lentiform nucleus and the thalamus. Both limbs meet at a right-angle called the genu.

The anterior limb is composed mainly of frontopontine fibres and thalamic radiations. The motor fibres converge at the genu and anterior or thalamolenticular component of the posterior limb. The corticospinal and corticobulbar tracts are the largest tracts. The most anterior fibres at the genu are those of the head. Fibres to the arm, hand, trunk, leg and perineum lie progressively more posteriorly. Haemorrhage or thrombosis of thalamostriate arteries supplying this area leads to paralysis of these muscles innervated by these fibres.

Behind these fibres on the posterior limb and on the retrolentiform part of the internal capsule are parietopontine and occipitopontine fibres. More posteriorly are the visual fibres that extend towards the occipital pole as the optic radiation. Most posterior of all are the auditory fibres.

RADIOLOGICAL FEATURES OF THE COMMISSURAL AND PROJECTION FIBRES

Plain Films of the Skull

Calcification of the habenular commissure is a common finding on skull radiographs. It is found anterior and superior to the pineal gland if this is also calcified. Typically, the calcification is C-shaped, with the open part of the letter facing backwards. Some authors suggest that this calcification is in the choroid plexus of the third ventricles – the taenia habenulare – rather than in the commissure.

CT and MRI

The corpus callosum is best assessed on sagittal and coronal imaging. On sagittal imaging the rostrum, genu, body and splenium form a rotated continuous C shape ( Fig. 2.5 ). The anterior and posterior commissures can also be seen on this view. A line joining the anterior and posterior commissures, the AC–PC line, is used as a reference in image-guided procedures.

On coronal MRI scans ( Fig. 2.7 ) the body of the corpus callosum and the tapetum can be seen superior to the lateral ventricles. On this view the anterior commissure may also be visible inferior to the third ventricle, but this commissure is best seen as an arc of fibres on axial MRI (see Fig. 2.6 ).

- 1.

Superior sagittal sinus

- 2.

Interhemispheric fissure

- 3.

Body of corpus callosum

- 4.

Tapetum

- 5.

Septum pellucidum

- 6.

Fornix

- 7.

Third ventricle

- 8.

Interpeduncular cistern

- 9.

Sylvian fissure

- 10.

Insula

- 11.

External capsule, claustrum and extreme capsule

- 12.

Lentiform nucleus

- 13.

Head of caudate nucleus

- 14.

Internal capsule

- 1.

Head of caudate nucleus

- 2.

Thalamus

- 3.

Globus pallidus

- 4.

Putamen

- 5.

Subthalamic nucleus

On axial imaging the internal capsule is seen as a V-shaped low-attenuation or high T 1 signal structure (see Fig. 2.3C ) between the caudate and lentiform nuclei anteriorly and the lentiform and thalamus posteriorly. On coronal imaging it can be seen lateral to the thalami. It is less well visualised on sagittal imaging.

Superficial subcortical white matter fibres are sometimes called U fibres because of their course on the deep surface of the gyri. These may be specifically involved or spared in different leukodystrophies and white matter disorders. These disorders affect various fibre tracts in different ways, some affecting predominantly deep white matter and some affecting predominantly superficial cerebral white matter and many spare the optic radiation. Optic nerve glioma preferentially affects parts of the optic nerve pathways and its location reflects the anatomical course of these fibres including involving connections to the lateral geniculate body of the thalamus, connections to the temporal lobe (Meyer’s loop) and brainstem.

Unmyelinated immature white matter because of its higher water content is darker on T 1 sequences and brighter on T 2 sequences than mature myelinated white matter. The progression of myelination can therefore be seen on MRI of infants. This progresses in a predictable way from deep to superficial, from posterior to anterior and from inferior to superior ( Fig. 2.8 )

Magnetic resonance tractography is a technique that uses diffusion tensor imaging to obtain images of fibre tracts within the brain. These scans also give information about fibre direction ( Fig. 2.9 ). Directionality is displayed using different colours with transversely orientated tracts typically presented in red, for example the corpus callosum, craniocaudally orientated tracts typically presented as blue, for example the corticospinal tract, and anteroposteriorly orientated fibres typically presented in green, for example the superior longitudinal fasciculus. Its main clinical application is in preoperative planning in order to preserve critical fibre tract function after surgery.

- 1.

Genu of corpus callosum

- 2.

Splenium of corpus callosum

- 3.

Posterior limb of internal capsule

- 4.

Tapetum and superior longitudinal fasciculus

Ultrasound Examination of the Neonatal Brain ( Fig. 2.10 )

The corpus callosum can be seen on midline sagittal scans as a thin band of tissue between the pericallosal artery in the pericallosal sulcus superiorly, and the fluid of the cavum septum pellucidum inferiorly. It is seen below the interhemispheric fissure on coronal scans, where both its upper and lower surfaces are perpendicular to the beam. On coronal scans the internal capsule can be seen lateral to the thalamus.

- 1.

Interhemispheric fissure

- 2.

Sulci

- 3.

Frontal horn of lateral ventricle

- 4.

Corpus callosum

- 5.

Caudate above, lentiform nucleus below, separated by internal capsule (these three are not distinguished separately)

- 6.

Sylvian fissure

- 7.

Brainstem

- 8.

Parahippocampal gyrus of temporal lobe

- 9.

Choroid plexus in atrium of lateral ventricle

- 10.

Calcarine sulcus

- 11.

Genu of corpus callosum

- 12.

Cavum septum pellucidum

- 13.

Cingulate gyrus

- 14.

Midbrain

- 15.

Pons

- 16.

Medulla

- 17.

Fourth ventricle

- 18.

Vermis of cerebellum

- 19.

Third ventricle

- 20.

Body of lateral ventricle

- 21.

Hippocampus

- 22.

Fornix

Basal Ganglia ( Figs. 2.11, 2.12 )

This subcortical grey matter includes:

- ■

The corpus striatum – the caudate and lentiform nuclei

- ■

The amygdaloid body

- ■

The claustrum

- 1.

Claustrum

- 2.

Head of caudate nucleus

- 3.

Internal capsule

- 4.

Lentiform nucleus

- 5.

Putamen

- 6.

Globus pallidus

The nuclei of the basal ganglia can be divided into input, output and intrinsic nuclei. The regulation of conscious and proprioceptive movements is the primary role of the basal ganglia. This is a complex process with many afferent input pathways including from the cortex, limbic system and gain-setting nuclei in the brainstem. The basal ganglia interpret these signals and determine which actions will take place through the disinhibition of these signals.

CAUDATE NUCLEUS

This nucleus is described as having a head, body and tail. Its long, thin tail ends in the amygdaloid nucleus. The caudate nucleus is highly curved and lies within the concavity of the lateral ventricle forming a C shape on sagittal imaging. Thus its head projects into the floor of the anterior horn and its body lies along the body of the lateral ventricle. Its tail lies in the roof of the inferior horn of this ventricle.

LENTIFORM NUCLEUS

The lentiform nucleus is shaped like a biconcave lens. It is made up of a larger lateral putamen and a smaller medial globus pallidus. Medially, it is separated from the head of the caudate nucleus anteriorly, and from the thalamus posteriorly by the internal capsule. A thin layer of white matter on its lateral surface is called the external capsule.

Strands of grey matter connect the head of the caudate nucleus with the putamen of the lentiform nucleus across the anterior limb of the internal capsule. The resulting striated appearance gives rise to the term corpus striatum .

The function of the corpus striatum is not well understood. It is part of the extrapyramidal system and influences voluntary motor activity. Cortical afferents enter the putamen and caudate nucleus, which send efferents to the globus pallidus. This in turn sends efferents to the hypothalamus, brainstem and spinal cord.

CLAUSTRUM (see Fig. 2.12 )

This thin sheet of grey matter lies between the putamen and the insula. It is separated medially from the putamen by the external capsule and bounded laterally by a thin sheet of white matter, the extreme capsule, just deep to the insula. The claustrum is cortical in origin. It may have a role in knowledge processing and in the synchronisation of motor and nonmotor processes.

RADIOLOGICAL FEATURES OF THE BASAL GANGLIA

CT and MRI

On axial CT or MRI at the level of the ventricles, the head of the caudate nucleus can be seen projecting into the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle (see Fig. 2.3C ). The head of the caudate nucleus is usually more radiodense than the lentiform nucleus or the thalamus, especially in older subjects. The body of the caudate nucleus is seen as a thin, dense stripe on the superolateral margin of the lateral ventricle on higher cuts.

The amygdala is an ovoid mass of grey matter at the anterior end of the tail of the caudate nucleus and can be seen on MRI anterior to the hippocampus in the medial temporal lobe (see Fig. 2.11 and later Fig. 2.16C ).

The connecting fibres between the lentiform and caudate nuclei that cross the anterior limb of the internal capsule and are responsible for the name corpus striatum, may also be seen on MRI.

The claustrum can be seen on MRI (see Fig. 2.12 ) as a stripe isointense with grey matter, separated from the putamen by the external capsule and from the insula by the extreme capsule.

MRI is sensitive to paramagnetic substances such as iron, which may be deposited in the globus pallidus, giving this a different signal intensity from the lentiform nucleus.

The tail of the caudate nucleus extends over the roof of the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle, where it should not be confused with heterotopic cortical grey matter.

Ultrasound Examination of the Neonatal Brain (see Fig. 2.10 )

The thalami and caudate heads can be seen on coronal images. Parasagittal scans are angled to show most of the lateral ventricle on one image. These show the head of the caudate and the thalamus forming the floor of the lateral ventricle.

The caudothalamic groove between the head of the caudate and the thalamus on the floor of the lateral ventricle is the commonest site of haemorrhage in preterm infants. The basal ganglia are the most common location for hypertensive haemorrhages in adults.

A number of neurodegenerative disorders selectively affect different components of the basal ganglia. Huntington’s disease results in atrophy of the caudate nucleus.

Thalamus, Hypothalamus and Pineal Gland

The structures around the third ventricle include the thalamus, hypothalamus and pineal gland. Together with the habenula these form the major structures of the diencephalon, a paramedian component of the forebrain.

THALAMUS

These paired, ovoid bodies of predominantly grey matter lie in the lateral walls of the third ventricle, from the interventricular foramen anteriorly to the brainstem posteriorly. Each has its apex anteriorly and a more rounded posterior end called the pulvinar. The thalamus is related laterally to the internal capsule and, beyond that, to the lentiform nucleus. The body and tail of the caudate nucleus are in contact with the lateral margin of the thalamus. The superior part of the thalamus forms part of the floor of the lateral ventricle.

The thalami are connected in the midline by the massa intermedia or interthalamic adhesion in 60%–90% of humans. Formerly thought to be non-neural connection, however, it does appear to contain some white matter tracts traversing to the contralateral hemisphere, suggesting a role as another commissure.

Most thalamic nuclei are relay nuclei of the main sensory pathways. Each sensory system, with the exception of olfaction, has a thalamic nucleus connected to a cortical area. Medial and lateral swellings on the posteroinferior aspect of the thalamus are called the geniculate nuclei. The medial geniculate nucleus is attached to the inferior colliculus and is involved in the relay of auditory impulses. The lateral geniculate body nucleus is attached to the superior colliculus and is involved with visual impulses. The thalamus receives its blood supply from thalamostriate branches of the posterior cerebral artery.

Separate to and below the thalami are paired nuclei called the subthalamic nuclei (see Fig. 2.7B ) which make up the majority of the subthalamus. They are connected to the globus pallidus and the substantia nigra. They play an important role in the regulation of movement helping to prevent unwanted movements. Destruction of one of them causes hemiballismus.

Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nuclei has been shown to be effective in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. This technique is dependent on accurate localisation of the subthalamic nuclei in axial and coronal MRIs. MRI also helps to identify anatomic variants or vascular lesions which could impact the approach or ability to perform this procedure.

Disorders of mitochondrial DNA and respiratory chain disorders may cause abnormalities of the basal ganglia on MRI. Abnormality of the subthalamic nuclei is particularly associated with cytochrome C oxidase deficiency.

HYPOTHALAMUS ( Figs. 2.13, 2.21 )

The hypothalamus is a bilateral paramedian group of nuclei surrounding and forming the floor of the third ventricle. It includes the following structures, starting anteriorly:

- ■

Optic chiasm.

- ■

Tuber cinereum – a sheet of grey matter between the optic chiasm and the mamillary bodies.

- ■

Infundibular stalk – leading down to the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland.

- ■

Mamillary bodies – small round masses in front of the posterior perforated substance in which the columns of the fornix (see below) end ( Fig. 2.17 ).

- ■

Posterior perforated substance – the interval between the diverging crura cerebri, which is pierced by central branches of the posterior cerebral artery.

The nuclei of the hypothalamus are connected by white matter, the medial forebrain bundle, to each other, to the frontal lobe anteriorly and to the midbrain posteriorly.

The function of the hypothalamus is maintenance of homeostasis by controlling autonomic, endocrine and somatic activity. As a result, it is widely connected to other structures. These include the cerebral cortex via the medial forebrain bundle, the brainstem via the dorsal longitudinal fasciculus, the hippocampus via the fornix, the amygdala via the stria terminalis, the thalamus via the mammillothalamic tract, the pituitary via the median eminence and the retina via the retinohypothalamic tract.

It has sympathetic and parasympathetic areas and plays a role in the regulation of temperature, appetite and sleep patterns.

The hypothalamus is supplied by branches of the anterior and posterior cerebral and posterior communicating arteries. Intercavernous veins draining the hypothalamus ultimately drain to the internal cerebral veins.

PINEAL GLAND (see Figs. 2.4 and 2.5 )

The pineal gland is an unpaired endocrine gland that lies between the posterior ends of the thalami and between the splenium above and the superior colliculi below. It is closely related to the cerebral aqueduct of Sylvius inferiorly. It is separated from the splenium by the cerebral veins. It lies within 3 mm of the midline.

The pineal stalk has superior and inferior laminae. The superior lamina is formed by the habenular commissure, and the inferior lamina contains the posterior commissure. Between these laminae is the posterior recess of the third ventricle.

The main known function of the pineal gland is in the regulation of the circadian rhythm of sleep through the secretion of melatonin.

Arterial supply is from choroidal branches of the posterior cerebral artery. Venous drainage is to the internal cerebral veins.

RADIOLOGICAL FEATURES OF THE THALAMUS, HYPOTHALAMUS AND PINEAL GLAND

Skull Radiographs

Pineal calcification is visible in approximately 50% of skull radiographs after the age of 10 years and in a greater percentage of CT scans (see section on the skull).

CT and MRI

The structures forming the hypothalamus can best be appreciated on midline sagittal MRI (see Fig. 2.5 ). The optic chiasm, the tuber cinereum, the infundibular stalk and the interpeduncular cistern, containing the mamillary bodies and in the base of which lies the posterior perforated substance, can be identified. The thalami can be seen on axial or coronal images on each side of the third ventricle (see Fig. 2.3C ). Their relationship to the posterior limb of the internal capsule and to the lentiform nucleus can be appreciated on this slice. The pineal gland and its superior and inferior laminae can also be best seen on midline sagittal MRI. Subthalamic nuclei can best be seen on coronal MRI (see Fig. 2.7B ).

Ultrasound Examination of the Neonatal Brain (see Fig. 2.10 )

In the parasagittal plane the thalamus can be seen in the floor of the lateral ventricle posterior to the head of the caudate nucleus. The relation of the thalami to the internal capsule is best seen on coronal ultrasound scans. On coronal views the interthalamic adhesion can be seen within the third ventricle, especially when the ventricle is dilated.

Masses of the pineal gland can present with obstructive hydrocephalus given the pineal gland’s close relationship with the cerebral aqueduct of Sylvius. Masses of the pineal gland can also present with Parinaud’s syndrome, a disorder of upward gaze and other abnormalities of vision and eye movement due to compression of the posterior commissure and upper midbrain.

Pituitary Gland (see Fig. 2.14 )

The pituitary gland (hypophysis cerebri) lies in the pituitary fossa or sella turcica of the sphenoid bone. On average it measures 12 mm in its transverse diameter, 8 mm in its anteroposterior diameter and 9 mm high. Its size, however, varies with age and gender. It is divided into anatomically and functionally distinct anterior (adenohypophysis) and posterior (neurohypophysis) lobes.

- 1.

Pituitary gland

- 2.

Pituitary stalk

- 3.

Optic chiasm

- 4.

Suprasellar cistern

- 5.

Cavernous sinus

- 6.

Internal carotid artery in cavernous sinus

- 7.

Sphenoid sinus

- 8.

Third ventricle

- 9.

Right anterior cerebral artery

- 1.

Optic chiasm

- 2.

Carotid artery

- 3.

Trigeminal ganglion in Meckel’s cave

The anterior lobe is five times larger than the posterior lobe. It is developed from Rathke’s pouch in the roof of the primitive mouth. (A tumour from remnants of the epithelium of this pouch is called a craniopharyngioma.) The anterior lobe produces hormones in response to release factors carried from the hypothalamus by hypophyseal portal veins, the hypothalamic-hypophyseal portal system.

The pituitary gland has a hollow stalk, the infundibulum, which arises from the tuber cinereum in the floor of the third ventricle. It is directed anteroinferiorly and surrounded by an upward extension of the anterior lobe, the tuberal part. This stalk is composed of nerve fibres whose cell bodies are in the hypothalamus. The posterior lobe is made up of the ending of these nerve fibres and releases hormones in response to impulses from these nerves.

The anterior lobe is adherent to the posterior lobe by a narrow zone called the pars intermedia. This is, in fact, developmentally and functionally part of the anterior lobe.

The relations of the pituitary gland are as follows:

- ■

Above: the diaphragma sellae (dura mater) forming the roof of the sella. Superior to this is the suprasellar cistern which contains a number of structures including the optic chiasm anteriorly (8 mm above dura) and the circle of Willis.

- ■

Below: the body of the sphenoid bone and the sphenoid sinus.

- ■

Laterally: the dura and the cavernous sinus and its contents, the internal carotid artery and abducens nerve with the oculomotor, ophthalmic and trochlear nerves in its walls. Inferior to the ophthalmic division of the fifth nerve is its maxillary division. More posteriorly in the posterolateral wall of the cavernous sinus lies the trigeminal ganglion in its CSF-containing arachnoidal pouch, Meckel’s cave (see Fig. 2.14C ).

The cavernous sinuses are united by intercavernous sinuses, which surround the pituitary gland anteriorly, posteriorly and inferiorly.

BLOOD SUPPLY

Superior hypophyseal arteries, which arise from each internal carotid artery immediately after it pierces the dura, supply the hypothalamus and the infundibulum. A capillary bed in the infundibulum gives rise to portal vessels to the anterior lobe. The posterior lobe is supplied by inferior hypophyseal arteries which arise from the meningohypophyseal trunk, a branch of the internal carotid arteries in the cavernous sinus.

Venous drainage is to the cavernous and intercavernous sinuses.

RADIOLOGICAL FEATURES OF THE PITUITARY GLAND

Skull Radiographs

The appearance of the bony pituitary fossa is affected by disease processes in the gland. This is dealt with in the section on the skull.

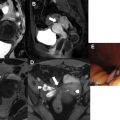

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (see Fig. 2.14 )

MRI is the primary modality for evaluation of the pituitary gland. Sagittal and coronal images are most useful. The size and shape of the normal pituitary gland vary. In adult males the gland ranges from 8 to 10 mm craniocaudal dimension in the sagittal plane. The dura above the sella should be horizontal, not convex. In females, the size of the gland varies with the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. In the postpartum period, it may normally exceed 12 mm in height. It is also normal for the gland to have a convex upper border in menstruating or lactating females. During puberty, the gland may also have a convex upper surface in both males and females. With increasing age and in postmenopausal females the gland reduces in volume.

In normal adults the anterior pituitary occupies 70–80% of the total gland volume and is isointense to cerebral white matter on T 1 images. The posterior pituitary usually has high signal intensity on unenhanced T 1 images due to the effect of stored neurosecretory granules on T 1 relaxation time. This so-called posterior pituitary bright spot is evident in most babies and children but is less consistently observed with increasing age in adults. The pars intermedia, a vestigial remnant of Rathke’s pouch, is not normally visualised on imaging studies. In some cases, a small cyst with variable signal intensity may mark the location of the pars intermedia.

The infundibulum tapers from the floor of the third ventricle to the pituitary gland. The diameter of the infundibulum should be no bigger than 3 mm or the adjacent basilar artery. It is a midline structure and displacement in either direction may signify an underlying pituitary mass. The sella itself is delineated by signal void of the bony cortex and by the high-intensity signal of marrow in the clivus. The optic nerves and chiasm and the intracranial carotid vessels above, and the sphenoid sinus below, are seen clearly on coronal sections.

Computed Tomography

CT has a limited role in the evaluation of the sella and suprasellar structures. The main role of CT is in the assessment of bony anatomy and changes in the sella, in the identification of calcification within lesions which can help narrow the differential diagnosis and in preoperative planning, where an intracranial CT angiogram can help delineate the local vascular anatomy to aid in surgical planning. Fine-cut coronal postcontrast images may be an alternative to MRI in patients who have a contraindication for MRI.

The Limbic Lobe System (see Fig. 2.15 )

This is not an anatomical lobe as such, but a large group of functionally related structures which anatomically lie lateral to the thalamus, about the corpus callosum and above the brainstem. The major components include cingulate, splenial and parahippocampal gyri, the hippocampus, amygdala, the dentate gyrus and the fornix, the olfactory bulbs and the hypothalamus.