12 The chest

Ultrasound of the pediatric chest is an area often neglected because of the presence of air in the lungs and the difficulty which the bony rib cage poses to access. However, as a result of the smaller footprint and higher resolution of modern equipment, there are a number of chest conditions where ultrasound can be usefully used in children. While CT and MRI are still considered the techniques for evaluating the chest, ultrasound has a definite and useful role in certain circumstances. In particular, ultrasound is most useful in the remote intensive care situation where children are often too ill and unstable to be moved to a scanner.1

TECHNIQUE OF ULTRASOUND EXAMINATION

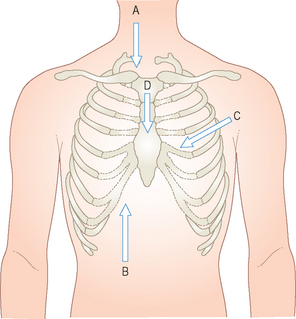

Depending on the location of the abnormality, different approaches can be used (Fig. 12.1).

Intrathoracic pathology is best examined using the intercostal and parasternal approaches. The posterior chest must always be examined in suspected pleural effusions, as fluid tends to accumulate posteriorly as the patient lies supine in bed.2

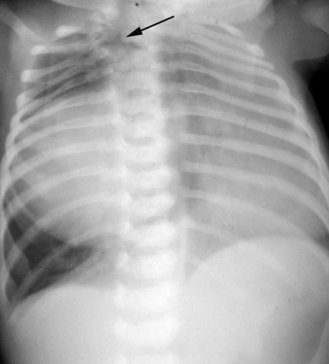

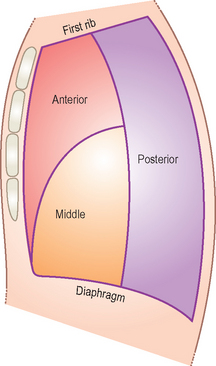

Mass lesions in the chest are usually described according to their location either in the anterior, middle or posterior mediastinum (Fig. 12.2).3 Table 12.1 gives a differential diagnosis of the more common masses seen in children and where they lie in the mediastinum.

Figure 12.2 The anterior, middle and posterior mediastinum. Table 12.1 gives a differential diagnosis of masses in these three regions.

Table 12.1 Causes of mediastinal masses

| Anterior | Middle | Posterior |

|---|---|---|

SVC, superior vena cava.

JUXTADIAPHRAGMATIC LESIONS

Lesions will fall into three broad groups:

Masses arising in the chest

The clue to the potential diagnosis will usually lie on the appearances on the chest radiograph and the clinical presentation. The contour of the mass and whether it is lying anterior or posterior in the chest is important in the differential diagnosis.4

Neurenteric cysts

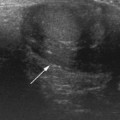

Neurenteric cysts are essentially cysts of bowel that have failed to separate from the neural canal during development. On the chest radiograph there may be a spinal abnormality, and usually this is higher than the lesion (Fig. 12.3). On ultrasound the neurenteric cyst has a well-defined border with a thin wall similar to a duplication cyst of the bowel. It may be completely hypoechoic or, if infection or hemorrhage has occurred, the cyst may contain cellular debris due to blood, mucus or white cells.

Pulmonary sequestration

Also called a bronchopulmonary foregut malformation, pulmonary sequestration refers to a segment of lung which does not function, has an anomalous arterial blood supply from the systemic circulation and has no communication with the tracheobronchial tree. It is due to a developmental abnormality in which there is an accessory tracheobronchial foregut bud.5