7 The female reproductive system

Introduction

Successful sonographic examination and evaluation of anatomy and disorders of sexual development in girls, requires an accurate knowledge and assessment of both uterine and ovarian size and morphology as they grow and develop throughout childhood. It is essential that the sonographer is able to assess the normal appearance, because disorders related to premature or late pubertal development form the bulk of the workload related to the female genital tract in childhood. In the young infant with conditions such as ambiguous genitalia or intersex, ultrasound has an important and useful role, so an understanding of what to look for in these disorders is also very important.1,2

EMBRYOLOGY

Development of the genital ducts

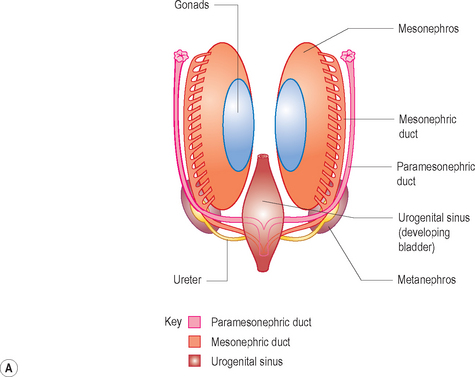

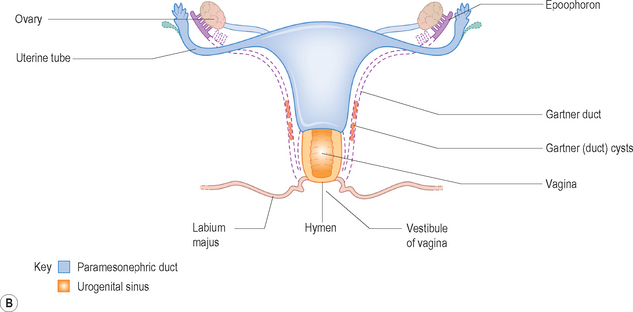

The paramesonephric ducts develop into the fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and upper vagina. The lower vagina develops separately from the urogenital sinus (Fig. 7.1).

Growth of the ovary

The complete unruptured Graafian follicle may regress without expelling the ovum, first by the oocyte dying and then undergoing necrosis with eventual formation of the corpus restiforme; this vanishes without trace. In fetal and postnatal life this generally occurs before the follicle has reached an appreciable size. If the follicle expels the ovum (ovulation) then either a fully developed corpus luteum will result, or the remaining follicle will become luteinized and regress without the development of a corpus luteum. The distinguishing feature of the post-pubertal follicle is the ability of the follicle to liberate its ovum (ovulation) and be converted into a corpus luteum.3

Endocrinology

In prepuberty, gonadotropin secretion can be measured but occurs in irregular bursts not linked to the night time. At about 7 to 8 years of age, pulsatile gonadotropin secretion becomes steadily linked to the night time and appears to be controlled primarily by the central nervous system. Throughout puberty the amplitude of gonadotropin pulses and gonadal sex steroid secretion gradually increases until late puberty, when adult levels are reached throughout the day. Although nocturnal pulsatility alone may permit menarche, usually anovulatory cycles, the development of diurnal and nocturnal high amplitude pulses is required for ovulatory cycles. Puberty ends with the final stage of ovarian maturation which is the establishment of regular ovulatory cycles. This reflects the maturation of the entire hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis.4

NORMAL APPEARANCES AND ULTRASOUND TECHNIQUE

The ovaries

The ovaries are active throughout childhood, with continual follicular growth and atresia. Ovarian maturation continues throughout childhood. There is continual growth in the size of the ovary with an increase in ovarian volume and an increase in number and size of the developing follicles as puberty approaches. It is often very surprising how follicular the ovaries of a child appear.5

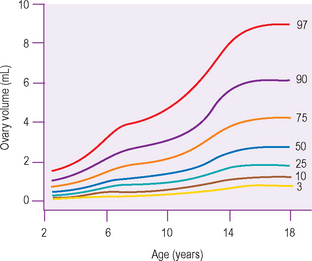

Ovarian volume

Studies have shown the ovarian volume to be 0.8 cm3 in the first 3 months of life, increasing in volume from a mean of 1 cm3 at 2 years of age to 2 cm3 at 12 years of age. Normal standards for ovarian volume in childhood and puberty are available.6 The volume of the ovary is affected by the presence of large cysts, either primordial or ovulatory follicles, or a corpus luteal cyst, and cannot be reliably calculated when these structures are present.

There appear to be two particular periods of increased growth rate of the ovary. The first occurs at approximately 8 years of age, coinciding with the rise in androgen secretion from the adrenal cortex at adrenarche. The second growth spurt occurs immediately before and during puberty (Fig. 7.2).6–13

Follicles

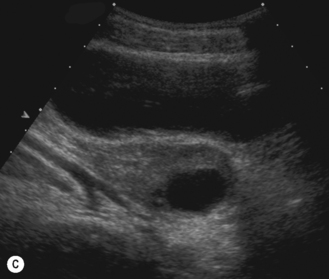

Throughout childhood the ovarian follicles increase in size and number. The size of the follicles varies and they may become atretic at any stage of their development. Prepubertally, the ovaries may appear quite active, with follicles of up to 9 mm in size. With the onset of high luteinizing hormone pulses at night, at about 8 to 9 years of age, the ovaries become ‘multicystic’ or multifollicular, defined on ultrasound appearances as more than six follicles of 4 mm diameter. This is a normal phase of development and is the herald of puberty.14

Menarche

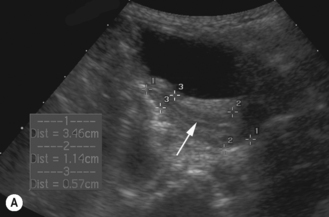

The principal regulators of ovarian function are luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). In response to rising levels of FSH, between 5 and 12 primordial follicles commence to enlarge and are now called primary follicles. The ovarian follicles gradually enlarge until a follicle of at least 16 mm is attained. There is follicular secretion of estrogen, which results in the development of an endometrium. Without ovulating (an anovulatory cycle), the follicle regresses, and the subsequent fall in estrogen results in a withdrawal bleed. Eventually, when a follicle diameter of over 20 mm is achieved, that follicle gains primacy, while the remainder of the other follicles recruited during the cycle degenerate. The remaining follicle is now known as a mature or dominant Graafian follicle. After ovulation the granulosa cells of the ruptured follicle wall begin to proliferate and give rise to the corpus luteum, which is an endocrine structure that secretes steroid hormones that maintain the uterine endometrium in readiness to receive an embryo. If no embryo implants in the uterus, the corpus luteum degenerates after about 14 days (Fig. 7.3).

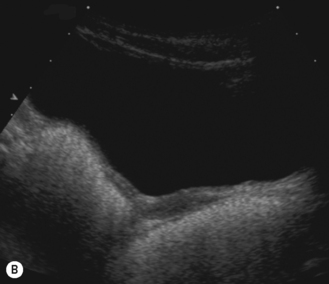

The uterus

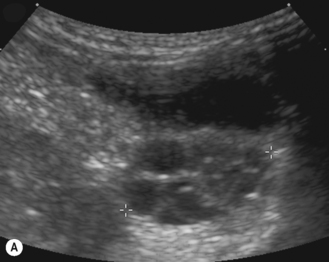

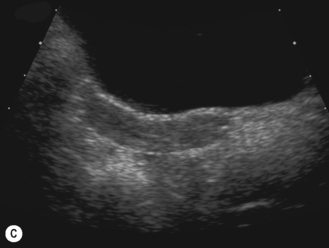

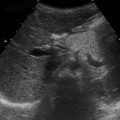

In the neonate, the uterus is still under the influence of maternal hormone stimulation and is large and plump. There is often a prominent endometrium, and uterine enlargement is predominantly of its corpus. Nussbaum et al found that the normal neonatal uterus was cylindrical in 58% and pear-shaped in 32%. The thin echogenic line of the endometrium can be identified in over 97% infants.15 If present, the neonatal uterus can always be identified (Fig. 7.4).

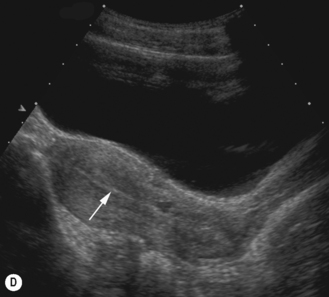

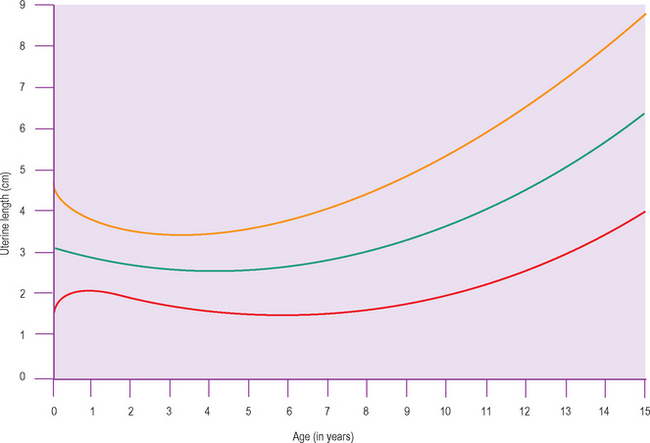

After birth the uterus diminishes in size and assumes a normal prepubertal configuration with prominence of the cervix. This is termed the teardrop-shaped uterus. It reaches a minimum length at about 4 years before increasing again.16

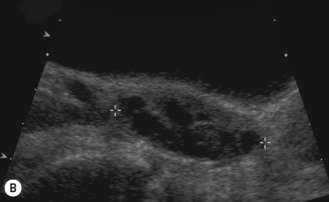

The endometrium is seen as an echogenic midline echo. Uterine volumes are available but a better measure of uterine growth and development is a uterine length and an AP measure of the body and cervix with an evaluation of their ratio. A simple indication of uterine growth is an AP measurement of the cervix, and as a general rule of thumb a measurement over 8 mm indicates growth has started (Fig. 7.5).