5 The liver, spleen and pancreas

The normal pediatric hepatobiliary system

Abnormalities of the neonatal liver

Abnormalities of the neonatal biliary system

Cystic dilation of the biliary system

Diffuse abnormalities of the pediatric liver

Focal lesions of the pediatric liver

Abnormalities of the gallbladder and bile ducts in childhood

LIVER

Embryology

Early in development of the caudal foregut the liver, gallbladder and bile duct arise as a ventral outgrowth. The developing liver bud grows into the septum transversum, which is a mass of mesoderm between the developing heart and midgut. The septum transversum ultimately goes on to form the ventral mesentery and central part of the diaphragm. The liver bud grows rapidly, filling a large part of the abdominal cavity in the first 10 weeks. The right and left lobes are about the same size but the right lobe soon becomes larger as a result of the supply of oxygenated blood from the umbilical vein. The liver starts producing blood cells at about 6 weeks, and bile formation starts by the 12th week. A small caudal outpouching of the hepatic diverticulum becomes the gallbladder, and the stalk of the diverticulum forms the cystic duct. The stalk connecting the hepatic and cystic ducts to the duodenum becomes the common bile duct (see Fig. 5.25).

Fetal vascular anatomy

In the fetal circulation the umbilical vein enters the left branch of the portal vein at the umbilical recess, lying in the free border of the falciform ligament from the umbilicus to the liver (Fig. 5.1). The left portal vein connects with the hepatic vein via the ductus venosus, and the blood then flows into the right atrium of the heart. The ductus venosus effectively forms a large venous shunt and bypasses the liver, allowing most of the blood from the placenta to pass directly to the heart. This fetal anatomy is important, as umbilical venous catheters should follow this route. If they enter the right portal vein then there is the potential for portal vein thrombosis to occur. After birth the umbilical vein obliterates and goes on to form the ligamentum teres in the falciform ligament. The ductus venosus also obliterates and goes on to form the ligamentum venosum. Within a few hours of birth and in very early neonatal life these structures can be readily identified with careful sonography. In the older child the ligamentum teres can be seen as an echogenic structure arising from the left branch of the portal vein (Fig. 5.2). When the pressure in the liver rises, as in cirrhosis, this channel re-canalizes and opens so that portal venous blood can flow away from the liver towards the umbilicus. This is how umbilical varices develop.

THE NORMAL PEDIATRIC HEPATOBILIARY SYSTEM

Ultrasound technique

Curved linear array transducers are undoubtedly the best probes to use for the liver and spleen and upper abdomen. They give a good overview with little degradation of the near field. Changing to a linear transducer is essential if there is any suspicion of disease causing subtle small foci, such as candida (see Fig. 5.16B), as these can be easily overlooked. High-quality Doppler is essential, as vascular abnormalities such as hemangiomas are common. Also, normal hepatic vascular anatomy and flow patterns should be confirmed.

Guidelines on technique are as follows.

• In children read the request carefully and check any previous reports or examinations. Always know what you are potentially looking for before you start, as the window of opportunity and period of goodwill for a quiet child is limited. Sedation, while rarely used for abdominal ultrasound, may be the only alternative when trying to clarify complex pathology, particularly when a good Doppler examination is needed.

• Children are best scanned supine at first, and visualization of organs is best enhanced by deep inspiration or expiration depending on which is better in any individual child. This exaggerated respiration brings the organs into better view. In inspiration the lungs inflate and the liver, spleen and kidneys descend below the ribs. This technique is also useful when trying to displace bowel. Sometimes in older children, organs will be better seen in the oblique and even decubitus position. The unwary sonographer must, however, accommodate the unusual views and appearances of the other organs such as kidney, IVC and aorta. An intercostal approach is very useful for a liver tucked high underneath the ribcage.

• Unless there is a suspicion clinically and a specific request to examine the biliary tree, children are not starved for routine abdominal examinations. If gallbladder or biliary disease is suspected during the examination, it is best to bring them back fully prepared and repeat the examination. One of the major advantages of ultrasound is that it can be repeated often and frequently.

• Ensure that the equipment is set optimally and a wide range of transducers is available for every eventuality.

• Have a systematic plan for examining the abdomen so that all the intra-abdominal structures are evaluated routinely. Leave any pathological process until last so that an important organ is not forgotten in the excitement of trying to come to a diagnosis.

• Remember to examine the intra-abdominal organs, both in longitudinal and transverse sections, in their entirety.

• The major abdominal vessels are important in children because organs, and in particular the liver, may have anomalous arterial supply and venous drainage. The IVC is particularly important and may be interrupted or may contain tumor or thrombus or a congenital web. The portal vein and porta hepatis should also be carefully examined for collateral vessels such as cavernous transformation.

• Don’t forget to look in areas often overlooked such as the subphrenic spaces, i.e. above the liver and spleen, the retroperitoneum and pelvis.

• Pay meticulous attention to the ultrasound examination first. Remember it is a dynamic examination and it is not always easy to produce images of what you are seeing.

Normal appearances of the liver

Size of lobes and segments

Requests for sonography in children with clinically suspected hepatosplenomegaly are common. Volumetric measurements are available in the literature, although they are not used in routine clinical practice.1

Hepatic vasculature

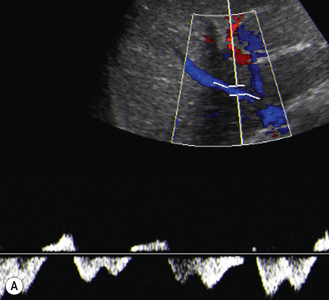

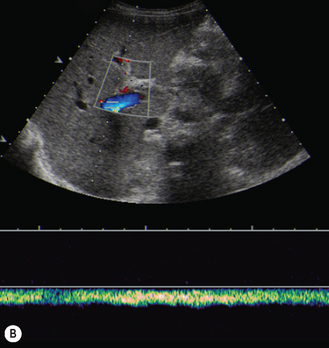

Figure 5.3 shows Doppler waveforms of the hepatic vessels.

Hepatic veins

The hepatic vein waveform is affected by:

• compliance, that is the flexibility of the liver, so that conditions affecting the liver parenchyma and ‘stiffening’ the liver will dampen the waveform

• cardiac status—there is normally reversal of flow in atrial systole but, if the heart is failing, the veins may massively dilate. In addition the IVC also dilates. There is loss of the normal fluctuation in the size of the lumen of the IVC and hepatic veins with respiration

• extrahepatic conditions such as ascites, which may compress the veins and change the normal waveform.

Portal vein

Normal diameter under 10 years of age should be in the region of 8 mm; over 10 years, it is 10 mm. Diameter is highly variable and varies with deep inspiration, food and posture. Normal waveform is monophasic with modulations due to respiration and cardiac activity.2,3

Normal appearances of the gallbladder and biliary tree

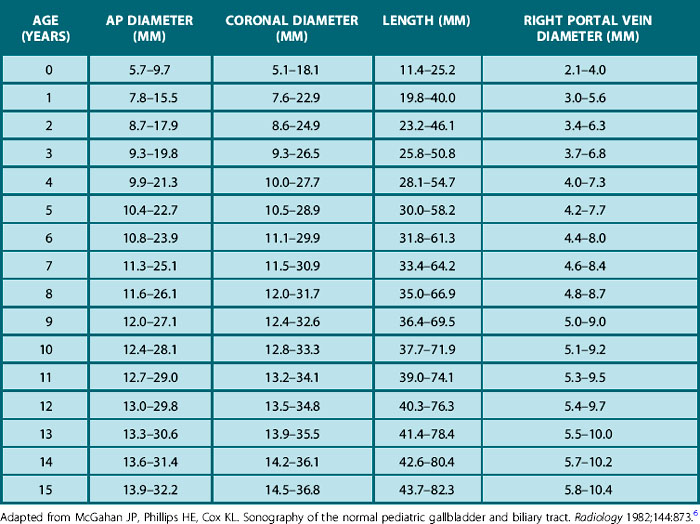

The gallbladder and biliary tree in a child are best examined after a fast. In infants, time the examination for the next feed if they are fed 4-hourly; in older children, a minimum of 6 hours’ fast is needed. Alternatively, give older children appointments for the first examination of the morning so that they can have an overnight fast. After an adequate fast, the normal gallbladder will be well distended with bile. The shape and size of the gallbladder are very variable (Table 5.1). In children, as in adults, folding of the gallbladder may be mistaken for a septum and, when this occurs, patients should be examined in the decubitus position, or even erect.

Table 5.1 Normal ranges (−2 SD to +2 SD) for the anteroposterior and coronal diameter as well as length of the gallbladder and diameter of the right portal vein

Congenital anomalies of the gallbladder are also quite rare, and intrahepatic gallbladder and duplication are probably the anomalies one is likeliest to see. Provided the infant or child is adequately prepared the sonographer should always expect to see the gallbladder in pediatric practice.4,5

Gallbladder wall thickness and common hepatic duct diameter show no significant change with age:6,7

ABNORMALITIES OF THE NEONATAL LIVER

Hepatomegaly

One of the commonest clinical indications for examining the neonatal abdomen is hepatomegaly. Box 5.1 lists the differential diagnoses.

Hemangioma and hemangioendothelioma

Diagnosis may be made in utero, and fetal hydrops may occur as a result of the AV shunting of blood.

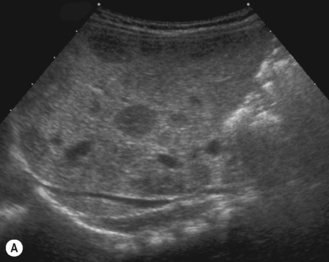

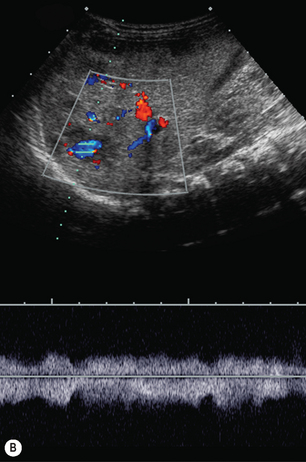

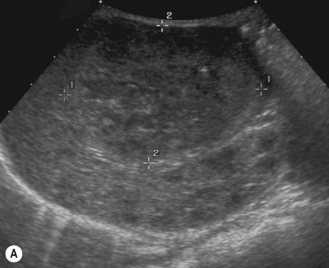

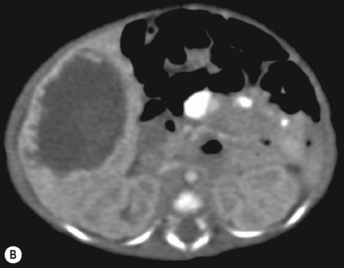

Ultrasound appearance

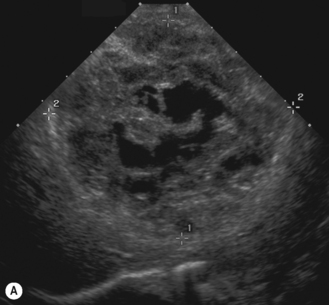

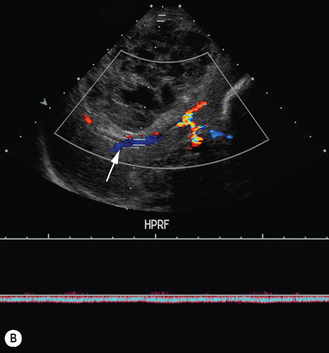

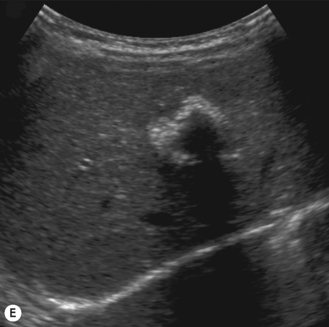

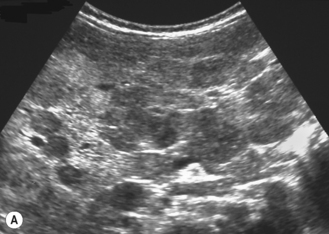

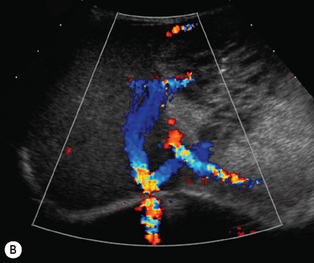

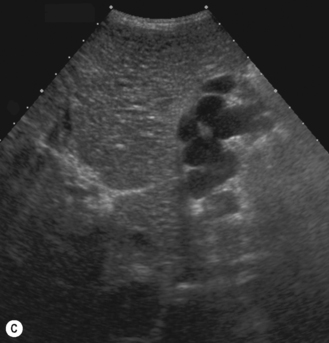

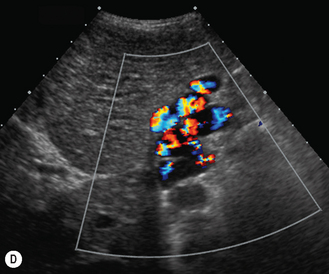

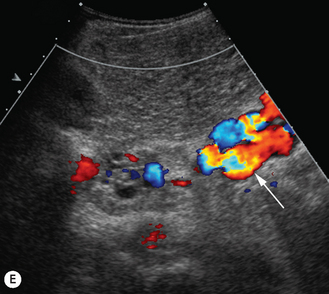

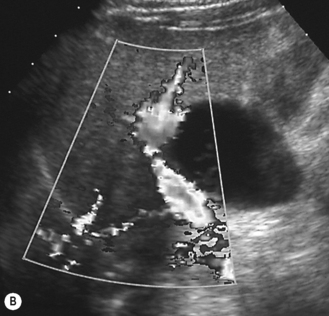

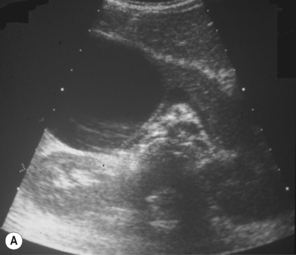

There is a wide spectrum of ultrasound appearances, from a single small hyper- or hypoechoic nodule to multiple similar nodules throughout the liver parenchyma (Fig. 5.4). Lesions may be present in the spleen as well. Calcification occurs in approximately 15%. They are highly vascular on Doppler examination but settings must be optimal for slow flow. Spectral traces should always be obtained from the hemangioma, which will demonstrate the AV shunting. Ultrasound is particularly useful to look at vessels both feeding and draining the hemangiomatous mass, so the aorta, celiac, superior mesenteric feeding vessels, and hepatic veins draining the mass need to be examined carefully. In addition this will also help in the differential diagnosis—if a mass is found in the liver in a neonate, with large feeding arteries and large draining veins, the diagnosis is most likely to be a hemangioma. In massive intratumoral AV shunting the patient may be in severe congestive heart failure. Ultrasonically the multiple small hemangiomas appear hypoechoic. The single hemangiomas may appear hyperechoic, as seen in adult hemangioma. An enhanced CT examination will show early peripheral enhancement with delayed progression to the center of the lesion. Occasionally the central portion of large masses will remain hypodense, and this corresponds to central fibrosis.

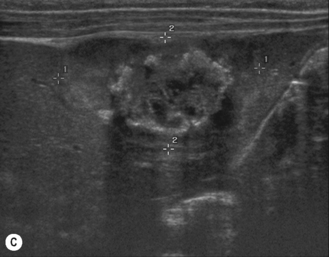

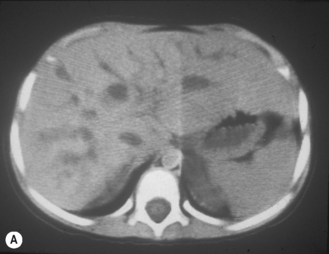

Cavernous hemangiomas contain large cystic spaces (Fig. 5.5). The sonographer must carefully evaluate the mass and examine the aorta and major blood vessels, as shunting of blood to the liver may be large and the diversion of blood may increase the size of the hepatic artery and superior mesenteric artery. Ultrasound is an excellent modality for demonstrating this in the neonate, as other cross-sectional imaging does not generally produce images of such exquisite detail due to the small size of the infant. Blood flow in the cavernous hemangioma may be slow and difficult to detect on Doppler but with newer equipment and optimal settings for slow flow this can be overcome. Very rarely these hemangioendotheliomas may fill the whole of the liver, producing a very specific and extraordinary appearance (Fig. 5.6). These infants may be in severe heart failure and have major problems with a bleeding diathesis. Sometimes extreme measures have to be taken in order for the infant to survive, and embolization of the hepatic artery has been attempted in order to prevent the shunting of blood.

These lesions are the most commonly seen hepatic masses in neonates and, provided the alfa-fetoprotein is normal, should be the first diagnosis excluded. It is for this reason that every effort must be made to perform a careful Doppler examination on all these patients (Fig. 5.7).

Liver tumors in the neonate

Hepatoblastoma

4S Neuroblastoma

4S NBL presents in the early neonatal period with a generalized enlargement of the liver and, on ultrasound, has a heterogeneous appearance typically described as a ‘pepper pot’ appearance. This should be the first differential diagnosis considered when a massively enlarged heterogeneous liver is found in the neonate and an active search for an adrenal primary tumor made. This is fully described in Chapter 4.

ABNORMALITIES OF THE NEONATAL BILIARY SYSTEM

Neonatal jaundice

Clinically the infants present in the first month of life with jaundice. The initial steps are:

• Confirm elevated bilirubin, of which more than 20% will be conjugated.

• Identify a potentially treatable cause such as sepsis or hypothyroidism or a metabolic condition (Box 5.2).

• Differentiate neonatal hepatitis from biliary atresia or a potentially surgically treatable condition such as a choledochal cyst. Ultrasound is an excellent modality to screen neonates with jaundice.

BOX 5.2 Causes of persistent neonatal jaundice

Conjugated > 20% total bilirubin

Biliary atresia

Ultrasound findings

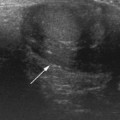

• Common bile duct. It is important to try to identify the common bile duct, which will be non-dilated in neonatal hepatitis and biliary atresia. In infants the normal common bile duct may be difficult to detect, and Doppler should always be used to confirm the position of the hepatic artery. The major differential is a choledochal cyst, so identification of a dilated common bile duct is crucial.

• Gallbladder. The infant must be adequately fasted. In biliary atresia the gallbladder is not always absent as previously thought but may be small and abnormal. Failure to find the gallbladder after an adequate fast is highly suggestive of biliary atresia.

• Intrahepatic bile ducts. These are not dilated in neonatal hepatitis or biliary atresia. They may be dilated in a choledochal cyst and in cholelithiasis or where sludge fills the biliary tree. Bile plug syndrome is a condition where pigment stones fill the biliary tree; some of the causes are total parenteral nutrition (TPN), furosemide treatment, dehydration, infection and prematurity. Sludge may be seen in the gallbladder.

• Portal cyst. A separate cyst may be seen in the porta hepatis in approximately 10% of patients. This is a remnant of the extrahepatic bile duct. It must not be confused with a choledochal cyst; if any suspicion exists, further imaging should be undertaken to determine the nature of the cystic structure. ‘Cysts’ may also be intrahepatic in location.

Role of ultrasound

The major role of ultrasound in neonatal jaundice is the following.

• Identify a cause of the obstructive jaundice that may be amenable to treatment such as dilation of the biliary tree—for example, a choledochal cyst or obstruction by inspissated bile or biliary calculi.

• Once these conditions have been excluded, the role of ultrasound is to try to differentiate biliary atresia from neonatal hepatitis. It must, however, be emphasized that there is no single biochemical test or imaging procedure that is entirely satisfactory to differentiate the two (Table 5.2).

Table 5.2 Differentiation of idiopathic neonatal hepatitis from biliary atresia

| Neonatal hepatitis | Biliary atresia | |

|---|---|---|

| Familial incidence | 20% | None |

| Size | Premature or small for gestational age | Normal |

| Stool | Usually persistently pale (acholic) | |

| Nasogastric aspirate | No bile | |

| Liver parenchyma | Normal or increased echogenicity | Normal or increased echogenicity |

| Bile ducts | Not dilated | Not dilated |

| Gallbladder | Normal Contracts after a feed | Contracted and abnormal 15% absent 10% normal |

| Associated anomalies | Polysplenia, pre-duodenal portal vein, diaphragmatic hernia, situs inversus | |

| HIDA scan | Poor uptake, but excretion into bowel | Good uptake, with no liver excretion into bowel |

| Other | Intra- or extrahepatic ‘cysts’; choledochocele | |

| Liver biopsy | Non-specific | Portal fibrosis |

| Diagnosis | ERCP or operative cholangiography outlines normal biliary tree | ERCP or operative cholangiography fails to outline normal biliary tree |

| Treatment | Treatment of the underlying cause if found | Early: hepatoportoenterostomy (surgical bypass of fibrotic ducts) Kasai procedure Late: liver transplantation |

ERCP, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; HIDA, hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid.

CYSTIC DILATION OF THE BILIARY SYSTEM

Congenital hepatic fibrosis

Congenital hepatic fibrosis may also be associated with Jeune syndrome, Meckel syndrome, chondrodysplasia syndromes and Zellweger syndrome (see Ch. 3, section on cystic kidneys).

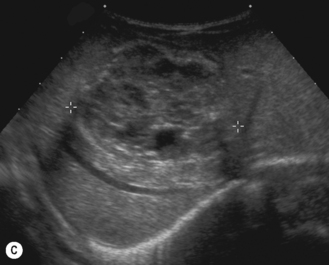

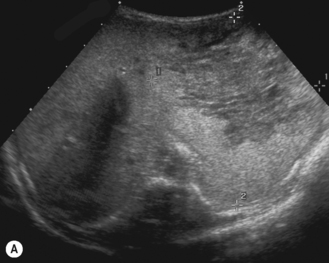

Caroli disease

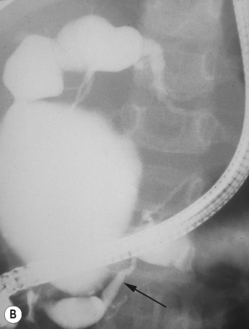

In the 1950s Caroli et al described a disease characterized by non-obstructive dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts. These cystic dilations of the bile ducts were prone to developing biliary calculi, and the patients were at risk of developing cholangitis. The disorder may be associated with congenital hepatic fibrosis and medullary cystic disease of the kidneys and a choledochal cyst (Fig. 5.9). Any infant or child with large echogenic kidneys and suspected of having ARPKD should have a careful evaluation of the liver. Polycystic disease of the liver is seen in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and differs in that the cysts do not communicate with the bile ducts. It rarely occurs in children.

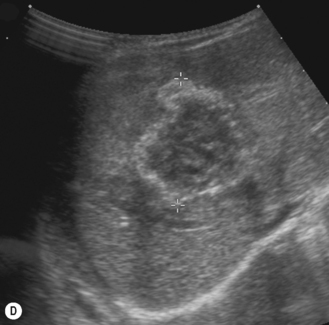

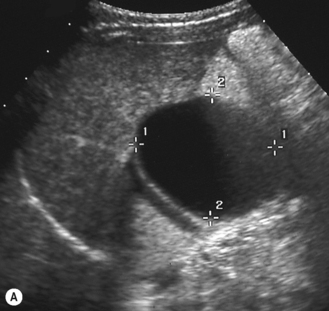

Choledochal cysts

These are cystic dilations of the extrahepatic biliary system.8–12 About 25% present in the neonatal period with cholestasis (Fig. 5.10). Some are detected by prenatal scanning. Choledochal cysts appear most commonly as cystic or fusiform dilation of the common bile duct. They are thought to be related to an anomalous connection between the common bile duct and pancreatic duct which results in chronic reflux of pancreatic juices and dilation of the common bile duct. Ultrasound is the initial imaging modality of choice and will generally give an excellent demonstration of the dilation of the intra- and extrahepatic biliary tree. ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) will further delineate the anatomy of the biliary tree (Fig. 5.11). Intraoperative (i.e. during surgery) cholangiography is also sometimes performed.