11 The musculoskeletal system

TECHNIQUE OF SCANNING MUSCLES AND SOFT TISSUES

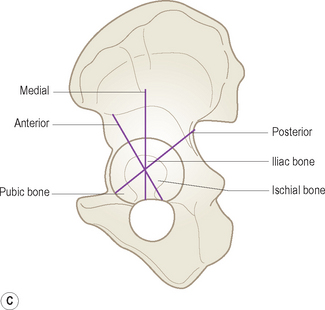

The measuring package for hip angles in developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a help.

DEVELOPMENTAL DYSPLASIA OF THE HIP

Since the early description in the late 1970s of the use of ultrasound in the diagnosis of hip abnormalities, ultrasound has increasingly been used as a tool to try and improve patient outcome and to improve diagnosis of this late presentation. The ability to see the cartilaginous acetabulum and femoral head on ultrasound has made it an exceedingly attractive choice of modality for examining the infant hip. Radiography at this early age is not useful for this condition, as the femoral head and a large component of the acetabular roof has not ossified. The unossified head and labrum can be clearly seen on sonography and, in addition, a dynamic assessment can be made where the head is manipulated in the acetabulum while the sonographer watches. Also the hip can be examined in a number of scan planes, which aids in the diagnosis. Arthrography was previously used to demonstrate abnormalities such as an inverted labrum and is occasionally still used.1–3

On the other hand the surgical treatment rate did not decrease significantly in newborns screened with ultrasonography compared with those screened by physical examination alone.4

Clinical tests

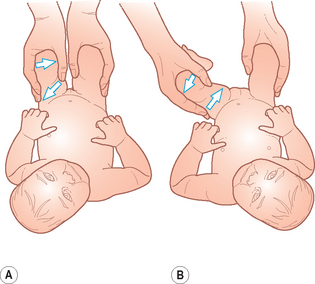

There are two clinical tests which help to identify unstable hips in newborn infants (Fig. 11.1):

• The Barlow test determines if a hip can be dislocated. The hip is flexed and the thigh adducted. With a gentle posterior pressure the femoral head can be made to move out of the acetabulum. This test actually dislocates the hip. So that when the hip is normally enlocated this test demonstrates whether the hip is partly or completely displaced out of the joint.

• The Ortolani test is the reverse of this test and relocates the head within the acetabulum. The hip is flexed and abducted and gently pulled anteriorly so that on examination a ‘click’, or the examiner feeling the dislocated femoral head moving over the acetabulum posteriorly and returning to the acetabulum, is felt. This identifies a dislocated hip and should demonstrate whether the hip is reducible.

There are a number of risk factors associated with developmental dysplasia of the hip:

• Family history of congenital dislocation of the hip is the most important risk factor. In some series of DDH up to 20% of infants treated had a family history.

• Female firstborn and pregnancies with oligohydramnios.

• A foot deformity that requires further treatment.

• A clicky hip as discovered on the Barlow or Ortolani test.

• Limb shortening. This is most apparently when the hips are flexed and the levels of the knees are compared.

• Leg posture. The thigh on the affected side tends to be held in partial lateral rotation, flexion and abduction.

• Thigh asymmetry. Different skin creases on the inside of the thigh may be apparent on the affected side.

• Limited abduction. In a supine position with the hips flexed, abduction may be limited as the femoral head remains dislocated.

Once the child is walking, other suspicious features are a limp or anxieties about the child’s walk, discrepancy in leg length and abnormalities of lower limb posture (Fig. 11.2).

TECHNIQUE OF HIP SCANNING

• Graf has devised a complex classification based on the acetabular structure and position of the femoral head. Several lines and angles are measured and a single coronal image is produced. There is no dynamic (i.e. scanning and watching the femoral head movement while under stress) component to his technique. A simplified version of his technique is probably the most widely practiced method in Europe: for example, Rosendahl and colleagues have adapted Graf’s method so that it assesses hip morphology and hip stability separately, to distinguish their relative importance for treatment outcome.

• Dynamic sonography of the infant hip, as described by Harcke, is a dynamic examination which stresses positional relationships and stability.

• The third technique is simply a line drawn down from the baseline which assesses what percentage of the femoral head is lying within the acetabulum.

The Graf technique

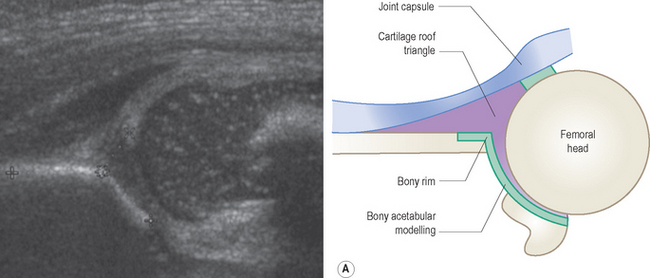

The Graf technique requires the sonographer to be able to identify important landmarks in the coronal plane and from these landmarks measure the alpha and beta angles. This technique requires some training and practice and the sonographer should ensure that they are adequately trained by an experienced practitioner in this method if it is to be used.5

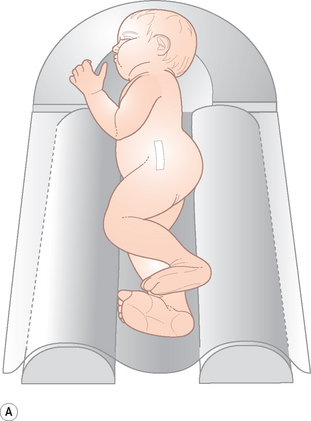

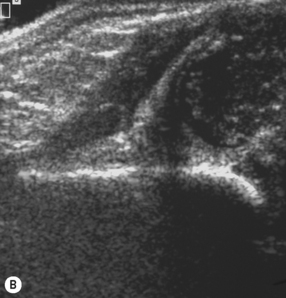

It is recommended that a positioning device is used to immobilize the patient. The infants are placed on their side and the transducer is placed over the greater trochanter (Fig. 11.3). The hip should be in slight flexion. When the trochanter, femoral neck and acetabulum lie in the same plane, this is optimal. The transducer is positioned so that it lies exactly in the frontal plane parallel to the body’s long axis and should not be tilted. The standard sonographic plane should be easily achieved in this position.

The following main reference points need to be identified:

• the cartilaginous portion of the acetabular roof

• the bony promontory of the superior bony acetabular rim

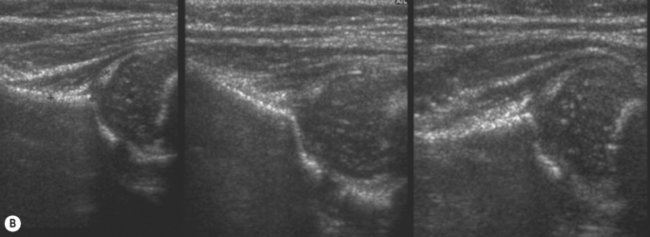

Once this standard plane has been achieved, the reference lines are drawn (Figs. 11.4 and 11.9).

Figure 11.4 Graf’s—standard plane. From this, the standard reference lines are drawn and the hip angles obtained. See also Fig. 11.9

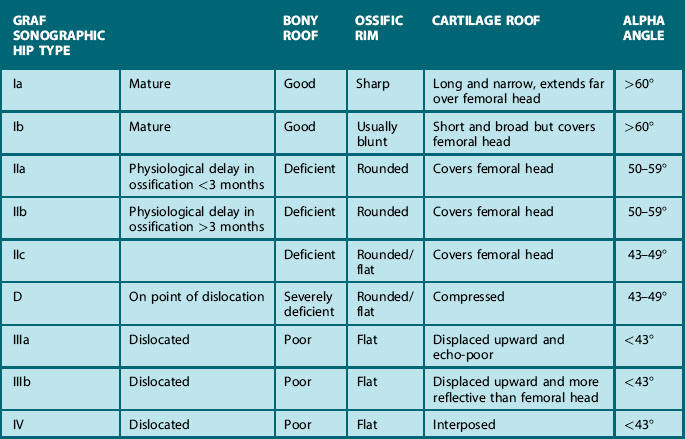

The alpha angle is described as the bony roof angle and is the most important to measure. The beta angle is the cartilaginous roof angle and is not universally used (Table 11.1).

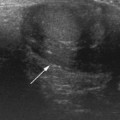

Table 11.1 is an adaptation of Graf’s classification of hip types. Types III (subluxation) and Type IV (dislocation) are probably the easiest to identify. Graf Type III involves persistent lateral displacement of the femoral head from the acetabular floor with deviation of the labrum. Type IV hips are complete dislocations, usually posterior and towards the head, with the femoral metaphysis obscuring the acetabular floor (Fig. 11.5).

• Type I are the mature hips with a deep acetabulum and angles over 60°.

• Type II a are those under 3 months of age with a shallow acetabulum and alpha angles of 50–59°. These are considered to be physiologically immature hips but stable.

• Type II b are the infants of over 3 months who have shallow acetabulae with alpha angles of between 50 and 59° who are also considered by Graf to be inherently stable.

• The most important group to identify for the sonographer are the unstable Type II c with shallow acetabulae and angles of 43–49°. These are considered to be unstable and require immediate treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree