The Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) has been the defining algorithm for professional reimbursement of medical services since its introduction in 1992. This article reviews the history of the RBRVS, with an emphasis on the integral involvement of the radiology and neuroradiology communities. Appropriate reimbursement of radiology procedures has been chaperoned by physician volunteers and society staff attending Current Procedural Terminology Panel meetings and American Medical Association/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee (RUC) meetings. In recent years, governmental and RUC initiatives have created an unfavorable environment for neuroradiologists to maintain reimbursement levels seen previously.

- •

The Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS), the foundation of physician professional payment in the United States, was established in 1992.

- •

Radiology had already established its own relative value scale (RVS), which was wholly incorporated into the RBRVS.

- •

The American Society of Neuroradiology first participated in the American Medical Association/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee (RUC) process in 1998, and has been actively engaged since then.

- •

In recent years the RUC, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee have squarely targeted radiology procedures for diminished valuation on multiple fronts.

Introduction

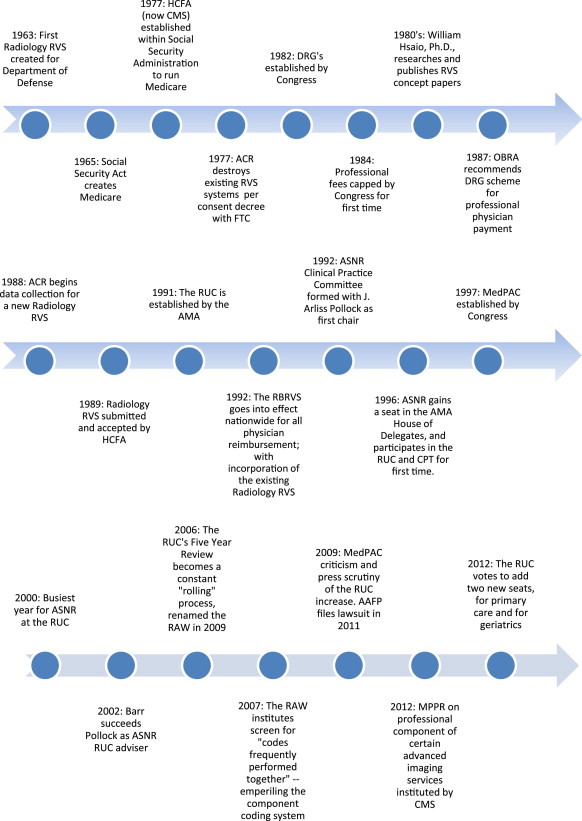

Before 1992, professional payment for Medicare services in the United States was fragmented, usually administered on a local or regional basis. There was significant geographic variation in reimbursement of doctors’ fees. With health care cost outlays accelerating rapidly in the 1980s, there was a call by Congress for greater oversight of distribution of government revenue for medical services. This led to the creation of the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS), which remains in force, with continual evolution, to the current day. The radiology community played a critical role, perhaps more than any other single medical specialty, in the acceptance of the relative value scale (RVS) system by the greater medical community. The neuroradiology community, despite its small numeric footprint nationwide, has participated actively in the evolution of this payment system.

Brief history of the RBRVS

The Medicare program was created by the Social Security Act of 1965, signed into law by then-President Lyndon B. Johnson ( Fig. 1 ). It reimbursed physicians for both their professional work and their direct practice expenses on an as-billed basis. There was a modest oversight program to confirm that reimbursement requests were in line with “customary, prevailing, and reasonable” charges, but no organized national basis or guidelines to maintain uniformity. The Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) was established in 1977 as a separate administrative entity within the Social Security Administration to run Medicare (HCFA was renamed the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS] in 2001).

This nonuniform scheme of reimbursement remained in force with minimal alteration into the 1980s. The 1982 Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act was passed into law partly in response to the burgeoning federal monetary outlays that occurred in the 1970s. It established the Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) system for payment of inpatient medical expenses: hospitals were subsequently paid an established fee for the cost of inpatient care based on specific diagnosis or diagnoses attributed to the patient. These fixed amounts were calculated by averaging actual hospital costs prior to that time. The legislation achieved its desired effect: inpatient costs to Medicare stabilized. There was a measurable decrease in inpatient days, and a shift to preferential outpatient care of medical illness and surgery.

This system also solidified a separation of physicians’ payments (which were not directly addressed by the DRG legislation) and hospital payments. Already in process, this program accelerated the increased prevalence of radiologists detaching themselves from hospital employment, with increased establishment of professional corporations that contracted with hospitals and maintained separate billing arrangements; in this way they untied themselves from the DRG model. This is also manifested by the separation of professional fees for interpretation of imaging studies from technical fees, the performance of the studies.

With the success of the DRG model at controlling hospital-based costs, then about two-thirds of Medicare’s budget, there was subsequently a call for control of physician payments. In 1984, professional reimbursement to physicians was frozen, at first for 1 year, then extended to a second. Physician charges to Medicare patients were also capped, limiting the previous custom of “balance-billing” beyond the maximum government payments. Attention was also directed toward perceived nationwide inequities in physician payment, both geographically and between specialists and primary care providers.

In an effort to control, monitor, and regulate physician payments, Congress commissioned William Hsaio, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, to establish a “relative value scale” (RVS) for professional payment. In a series of research articles in the 1980s, he had proposed and justified such a system, and had become a national spokesperson in this concept.

An RVS is a means of estimating the discrete amount of work that goes into providing a specific medical service in relation to other procedures; that is, to create a schedule or table that ranks procedures in order. To do this, the concept of “physician work” first needed to be defined. Hsaio’s system did this by estimating the amount of time a procedure required, and the difficulty or intensity of the procedure. Intensity was defined by 3 subcategories: technical skill or physical effort; mental effort or judgment; and stress. The latter concept of psychological stress was used as a surrogate for the possibility of being subjected to a lawsuit in the event of an untoward outcome. Thus procedures that took a long time, but which were easier to perform and less likely to lead to a malpractice action, might be valued less than a procedure requiring less time but which was more intense, challenging, and stressful. The essential technique by which Hsaio had physicians estimate their work was a statistical concept of “magnitude estimation”: by simply asking a sufficient number of physicians how they would rank a list of procedures from the least amount of work to the greatest (while keeping in mind the 3 metrics listed above), a statistically reliable and reproducible means of creating an RVS was established. In addition, Hsaio acknowledged and incorporated the concept that practice expenses were an essential ingredient in physician reimbursement.

Brief history of the RBRVS

The Medicare program was created by the Social Security Act of 1965, signed into law by then-President Lyndon B. Johnson ( Fig. 1 ). It reimbursed physicians for both their professional work and their direct practice expenses on an as-billed basis. There was a modest oversight program to confirm that reimbursement requests were in line with “customary, prevailing, and reasonable” charges, but no organized national basis or guidelines to maintain uniformity. The Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) was established in 1977 as a separate administrative entity within the Social Security Administration to run Medicare (HCFA was renamed the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS] in 2001).

This nonuniform scheme of reimbursement remained in force with minimal alteration into the 1980s. The 1982 Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act was passed into law partly in response to the burgeoning federal monetary outlays that occurred in the 1970s. It established the Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) system for payment of inpatient medical expenses: hospitals were subsequently paid an established fee for the cost of inpatient care based on specific diagnosis or diagnoses attributed to the patient. These fixed amounts were calculated by averaging actual hospital costs prior to that time. The legislation achieved its desired effect: inpatient costs to Medicare stabilized. There was a measurable decrease in inpatient days, and a shift to preferential outpatient care of medical illness and surgery.

This system also solidified a separation of physicians’ payments (which were not directly addressed by the DRG legislation) and hospital payments. Already in process, this program accelerated the increased prevalence of radiologists detaching themselves from hospital employment, with increased establishment of professional corporations that contracted with hospitals and maintained separate billing arrangements; in this way they untied themselves from the DRG model. This is also manifested by the separation of professional fees for interpretation of imaging studies from technical fees, the performance of the studies.

With the success of the DRG model at controlling hospital-based costs, then about two-thirds of Medicare’s budget, there was subsequently a call for control of physician payments. In 1984, professional reimbursement to physicians was frozen, at first for 1 year, then extended to a second. Physician charges to Medicare patients were also capped, limiting the previous custom of “balance-billing” beyond the maximum government payments. Attention was also directed toward perceived nationwide inequities in physician payment, both geographically and between specialists and primary care providers.

In an effort to control, monitor, and regulate physician payments, Congress commissioned William Hsaio, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, to establish a “relative value scale” (RVS) for professional payment. In a series of research articles in the 1980s, he had proposed and justified such a system, and had become a national spokesperson in this concept.

An RVS is a means of estimating the discrete amount of work that goes into providing a specific medical service in relation to other procedures; that is, to create a schedule or table that ranks procedures in order. To do this, the concept of “physician work” first needed to be defined. Hsaio’s system did this by estimating the amount of time a procedure required, and the difficulty or intensity of the procedure. Intensity was defined by 3 subcategories: technical skill or physical effort; mental effort or judgment; and stress. The latter concept of psychological stress was used as a surrogate for the possibility of being subjected to a lawsuit in the event of an untoward outcome. Thus procedures that took a long time, but which were easier to perform and less likely to lead to a malpractice action, might be valued less than a procedure requiring less time but which was more intense, challenging, and stressful. The essential technique by which Hsaio had physicians estimate their work was a statistical concept of “magnitude estimation”: by simply asking a sufficient number of physicians how they would rank a list of procedures from the least amount of work to the greatest (while keeping in mind the 3 metrics listed above), a statistically reliable and reproducible means of creating an RVS was established. In addition, Hsaio acknowledged and incorporated the concept that practice expenses were an essential ingredient in physician reimbursement.

The role of radiology in the adoption of the RVS

Less well known than Hsaio’s arrival on the national payment scene is the key role played by the radiology community in the adoption of the RVS system. Radiology’s efforts to establish an RVS actually predated Hsaio; and during the 1980s, radiology’s RVSs were being revised and updated contemporaneous with Hsaio’s efforts.

Radiology initially established an RVS of its own as early as 1963 in response to a request from the Department of Defense for its own insurance program for military and dependents. In 1965, the American College of Radiology (ACR) revised this initial charge-based scale to base its system on “time and effort devoted by the radiologist.” Additional revisions followed in 1969 and 1973, the latter including practice expenses incurred for each procedure. There was a temporary moratorium on development and promulgation of RVSs in the mid-1970s resulting from a decree by the Federal Trade Commission that such systems were anticompetitive. All previously established RVSs were actually deleted by the ACR. However, when the legislative tide turned back toward the use of RVSs in the 1980s, the ACR’s previous work in this area was resurrected.

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA1987), based on the success of the earlier cost-control efforts detailed above, included multiple provisions that we now recognize as inherent to the health care payment system in the United States: budget neutrality, with establishment of an annually adjusted conversion factor; allowance for scheduled geographic variation in costs; further limitations on (and ultimately proscription of) balance-billing above the allowed Medicare charges; and that such an RVS would be created in collaboration with provider stakeholders (for instance the ACR) and legislative review. The latter was enabled by the newly formed Physician Payment Review Commission (PPRC), an advisory body made up largely of physicians, whose stamp of approval significantly facilitated Congressional action. However, OBRA1987 contained another provision that galvanized the radiology community: rather than wait for Hsaio’s RVS work to be completed, it directed the HCFA to develop DRGs for payment of hospital-based specialty physicians (radiology, anesthesia, and pathology), and directed that such a system be adopted for the 1989 Federal Budget.

The threat of Federal government fee-setting for radiology services was acted on swiftly and effectively by the ACR. In addition to a presumed decrease in professional revenue, there was the strong likelihood that hospitals would again become the dominant employer of radiologists under such a system. In congressional testimony, the ACR volunteered to work with Congress, the HCFA, and the PPRC to develop an alternative means of reimbursing radiologists that would be acceptable to Washington. In consultation with the PPRC and the HCFA, and based on its earlier experience, the ACR created a new radiology RVS. Magnitude estimation data (in the form of surveys of 45 radiology services) were collected; these data was refined by consensus of expert panels of radiologists; and then extrapolated to include every radiology service then described (numbering 740) in the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) guidebook of the American Medical Association (AMA). One hundred ten other services outside the radiology section, but also commonly performed by radiologists, were also ranked. The data collection specifically requested information on the key concepts described above: the time required for a service; and physician effort, including the subcategories of technical skill or physical effort, mental effort or judgment, and stress. This overall assessment of physician work was termed “complexity,” and some of the parameters measured by Hsaio were rephrased (component dimensions included time, mental effort, technical skill, quality control and assurance, and potential harm to patient).

Two thousand work surveys were sent out to practicing radiologists in 1988; 1022 responses were received. Three thousand surveys on professional and global charges were sent; almost 1800 were received. Data on practice expense were collected by an independent professional consulting group from 400 practices nationwide. The results were subsequently analyzed by ACR subcommittees of diverse background and subspecialty. The intravenous pyelogram was chosen as the key reference procedure for the entire spectrum, and set at an arbitrary nonmonetary value of 100. With the survey results of the 45 “primary” services in hand, and with the advice of the subspecialty committees, the ACR’s steering committee established an RVS for more than 800 procedures by magnitude estimation in a matter of months through numerous meetings and conference calls. The sheer size of this data collection and analysis, especially in view of the pencil-and-paper nature of the surveys, and the compressed time frame in which it occurred, remains an achievement of staggering proportions to this day. Based on the compelling strength of the work performed by the ACR, the HCFA accepted the submitted recommendations for professional relative work values in radiology for the 1989 budget without change, predating the HCFA’s adoption of Hsaio’s system for the rest of medicine by 3 years. The only amendment was that the HCFA declined to accept ACR’s recommendations for those procedures outside the Radiology section of the CPT guidebook.

The HCFA instituted the so-called RBRVS for the entire Medicare fee schedule, phased-in between 1992 and 1996, based mostly on Hsaio’s work. Hsaio’s RBRVS adopted the radiology RVS in toto, without adjustment, which is further testimony to the statistical strength of the ACR effort. Besides establishing reliable reimbursement schedules for Medicare patients, many private payors use the Medicare fee schedule as a basis for their own, emphasizing its critical role.

The rise of component coding

In the establishment of the radiology RVS, and the nascent establishment of the national RBRVS for Medicare, local discrepancies in the coding of interventional procedures were uncovered. Specifically, some Medicare carriers reimbursed interventional procedures in a bundled manner, whereas the radiology RVS and the ACR advocated billing on a component basis; that is, separate codes for supervision and radiologic interpretation (S and I) of interventional procedures apart from the billing of the surgical procedure itself. Further, some carriers would reimburse for a complete surgical procedure as if a single procedure had been performed, whereas others reimbursed separately for the discrete building blocks of the entire surgical portion of an interventional procedure. The ACR was insistent that the latter component-based system was appropriate, both for more accurate reimbursement and for better tracking of procedures for quality control, practice expense, and trend analysis. Through dedicated efforts on the part of ACR and the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) (then the Society of Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology), in the form of numerous negotiations and proposals with the HCFA, a nationwide standardized approach of component coding and reimbursement was adopted into the radiology RVS in 1991, and subsequently incorporated into the RBRVS.

The RUC

One of PPAC’s recommendations to Congress made during consideration of a national Medicare RBRVS was to establish an expert multispecialty consensus panel that would be charged with ongoing review of the accuracy of the RBRVS, and that would determine appropriate rank-order placement of newly introduced procedures into the system. Thus was born the RUC, an acronym for the American Medical Association/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee, which continues its work on an advisory basis to CMS to the present day. The RUC first met in May 1991. As further evidence of the respect with which ACR’s process was regarded, the nascent RUC sought advice and input from the ACR on its successful survey model.

During the thrice-yearly RUC meetings, advisors from medical specialty societies (now more than 100) present recommendations to the Committee regarding their assessment of the relative value of procedures performed by its members. The Committee currently consists of 29 members, 23 of whom are physicians nominated by the major specialty societies ( Box 1 ). Radiology holds a seat on the Committee, and the ACR nominates a Member who serves upon the approval of the AMA. The other radiology societies regularly in attendance at RUC meetings are the American Society of Neuroradiology (ASNR) and SIR. The Society of Nuclear Medicine (SNM) also attends faithfully. The representatives of these societies have formed a close working bond over the years, persevering through occasional changes in personnel.

Chair

American Medical Association Representative

CPT Editorial Panel Representative

American Osteopathic Association Representative

Health Care Professionals Advisory Committee Representative

Practice Expense Subcommittee Representative

Anesthesiology

Cardiology

Cardiothoracic surgery

Dermatology

Emergency Medicine

Family medicine

General surgery

Internal medicine

Neurology

Neurosurgery

Obstetrics/gynecology

Ophthalmology

Orthopedic surgery

Otolaryngology

Pathology

Pediatrics

Plastic surgery

Psychiatry

Radiology

Urology

Infectious Disease

Rheumatology a

Vascular surgery a

Primary care b

Geriatrics b

a Rotating seat: not specifically designated for those specialties.

b Added in 2012.

The process of the RUC meeting has evolved over the past 20 years, but its mission has remained focused: to cogently place a procedure in its appropriate place in the hierarchy of professional medical work by assigning a defensible relative value unit (RVU) value. The values suggested by the societies are debated, and frequently revised by the Committee. The RVU values decided on by the RUC are then passed along to the CMS, who may adopt these values, or change them to their liking, before incorporating them into the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS). The RUC has been, and remains, the primary advisory body supplying information and recommendations to CMS for professional work valuation and practice expense ( Fig. 2 ).

In the 20 years of its existence, the RUC has provided a very effective service to CMS. More than 90% of its RVU recommendations have been accepted by the CMS in its annual PFS. This track record stalled somewhat in 2011, when the CMS accepted just 85% of the RUC’s recommendations, revaluing the other 15% in its Proposed and Final Rules.

Societies develop their recommendations to the RUC by means of standardized surveys that are sent to their membership. The physician completing the survey is asked to assess the amount of time a procedure takes; how it ranks in terms of work compared with a list of comparable procedures provided by the specialty; and to compare the procedure in question with the most commonly chosen reference service for “intensity and complexity.” These questions ask the responder to quantify the technical skill, physical difficulty, and mental stress of the examination.

One of the key elements of the RUC process is the concept of budget neutrality: increasing the RVU value of one procedure in a zero-sum system will lead to less reimbursement for all other procedures. There is an obvious incentive to achieve maximal achievable RVU values for codes that one’s own society members perform, and to critique (where possible) other societies’ attempts to maximize their code values. This potentially antagonistic situation is tempered by the frequent need for cooperation between societies to present codes together in frequently shifting alliances. Furthermore, voting members of the RUC itself are specifically barred from advocating for code valuations presented by the societies they represent; they are charged with sitting as impartial judges of valuation. These checks and balances tend to dampen intersocietal conflict.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree