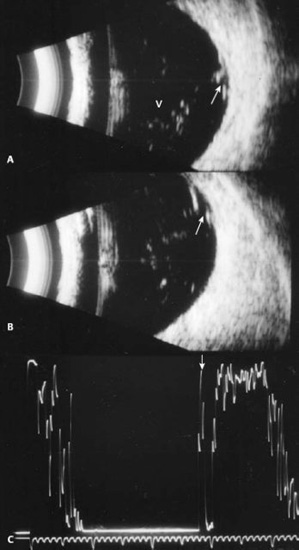

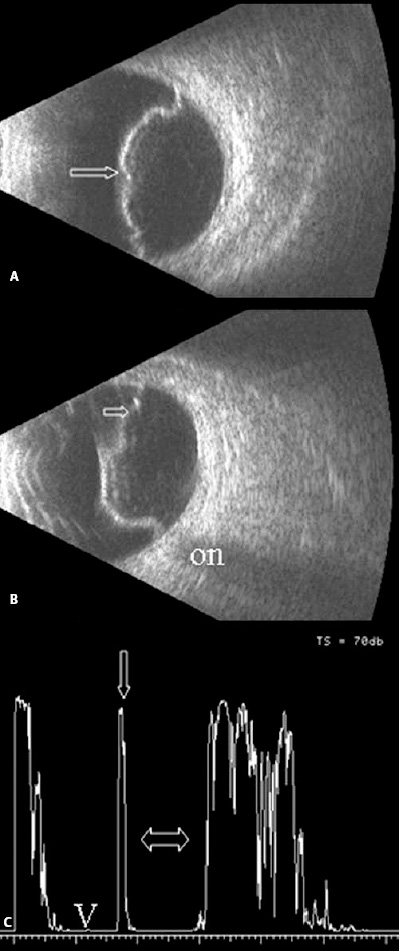

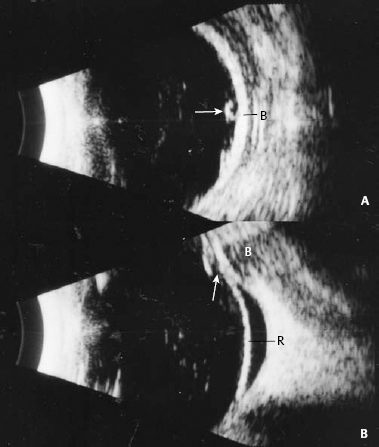

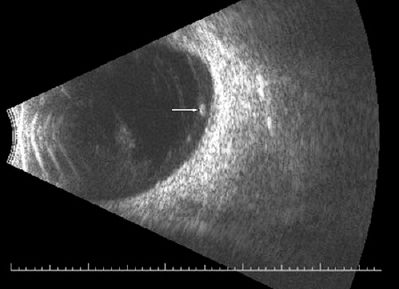

4 Ruling out the presence of retinal detachment is probably the single most important task for the echographer. Whether there is a dense cataract, a vitreous hemorrhage, an inflammatory process, or following trauma, the status of the retina is the most commonly asked question. Therefore, it is essential that the echographer recognizes the echographic features of a retinal detachment and is able to differentiate retina from other membranes (e.g., posterior vitreous detachment, PVD; layered hemorrhage; choroidal detachments). The retina is a somewhat dense tissue that when detached, will display a thick, folded membrane on contact B-scan images. It may also exhibit some movement, depending on the length of time it has been detached. There can be varying degrees of retinal detachment, and often localized detachments can be difficult to differentiate from dense vitreous membrane formation. When the retina is totally detached, it almost always inserts into the optic disc. The funnel shape produced by a total detachment may be widely opened, narrowly closed, or any variation in between. In long-standing detachment, there may be cyst formation, subretinal hemorrhage/cholesterol, or even calcification of the retina. The contact B-scan evaluation provides the topographic features of retinal detachment (total, dense, thick, folded), as well as the location, extension, and mobility. The standardized A-scan is used to confirm the diagnosis of retinal detachment. Because the retina is a dense membrane, when the sound beam is aimed perpendicular to the retinal surface, a maximally high (100%) spike will be produced. When there is an extensive or total retinal detachment, this high spike can be followed from the posterior pole and will remain separate from the adjacent fundus spikes (choroid, sclera) to the ora, where it has a very strong adhesion. Traction retinal detachments are caused by the adherence and pulling of vitreous membranes, bands, or the posterior hyaloid surface to areas of the retina. These adhesions can be focal in nature, causing a tent-like area of traction retinal detachment, or more broad, creating a “tabletop” traction detachment. Traction detachments can also be complex, involving extensive areas of the fundus, especially in patients with diabetic eye disease. The best way to map the extent of these detachments is by performing contact B-scan using longitudinal probe positions in all clock hours to determine all areas of vitreoretinal adhesion. Meticulous evaluation of the region of the macula is of primary importance. This can be accomplished using four different probe positions. The first, and generally the least helpful, is a vertical transverse scan directed toward the temporal posterior pole (9P OD, 3P OS). Longitudinal scans directed toward the temporal fundus are often the most helpful. The probe should be placed on the nasal fundus with the marker directed at the limbus with the sound beam aimed opposite the probe (L9 OD, L3 OS). If the patient does not have an intraocular lens implant, performing horizontal axial or vertical macula scans can be very useful. To perform these scans, the patient should be instructed to look in primary gaze. A generous layer of methylcellulose should be placed on the probe face, and the probe should then be gently placed on the cornea. In horizontal axial scans, the marker is directed toward the nose. In the echogram, the macula will be located just below the optic nerve shadow. In vertical macula scans, the marker is directed toward the 12-o’clock meridian (the lens and optic nerve are displayed). The sound beam is then aimed slightly toward the temporal posterior pole just until the optic nerve shadow disappears. The macular region will be observed in the center of the echogram. Small retinal tears can be easily detected in patients with spontaneous vitreous hemorrhage. Most commonly, tears are located in the superotemporal or superonasal periphery; however, they can be in any peripheral location. Screening the eye in all quadrants and shifting the probe from the limbus into the fornix is essential; failure to do this may lead to misdiagnosis and possibly delayed treatment. During contact B-scan evaluation, small retinal tears appear as highly reflective tufts of elevated tissue. Commonly, a thin vitreous membrane can be observed that is adherent to the highly reflective tuft of tissue. On standardized A-scan, retinal tears will produce a maximally high spike that is separate from the adjacent fundus spikes but can be difficult to display because of the small size and peripheral location. When marked hemorrhage is present and small tears cannot be visualized ophthalmoscopically, ultrasound-guided cryotherapy has been an effective alternative for early treatment and prevention of progressive retinal detachment. Retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) detachments and retinoschisis are easily detected with ultrasound. Typically, an RPE detachment is represented as a localized, dome-shaped membrane on B-scan, most often located posterior to the equator. If hemorrhage is present beneath the area of the RPE detachment, this lesion could easily be misdiagnosed as a tumor. On standardized A-scan, RPE detachments produce a maximally high thin spike. The thinness of this spike is often the key to the echographic diagnosis. Serial ultrasounds may be helpful in monitoring the elevation and internal reflectivity of the lesion if there is concern that a mass may be present. Retinoschisis appear as elevated, smooth, thin, dome-shaped membranes that are often bilateral and located in the inferotemporal periphery. The elevation of retinoschisis may vary from shallow to bullous, and they can be asymmetric. On standardized A-scan, retinoschisis displays a very thin, maximally high spike and often slight vertical after movement can be observed. Because retinoschisis often occur bilaterally, examination of the fellow eye can be beneficial in confirming the diagnosis. Infants, especially small premature ones, can be very difficult to evaluate with ultrasound. Partly because the probe is large compared with the size of their tiny heads and eyes and partly because they cannot cooperate and fixate as needed. It is most effective to perform longitudinal scans in as many meridians as possible to confirm the presence of a funnel-shaped membrane extending to the optic disc. When a patient suffers from cerebral hemorrhage from trauma or other etiology, hemorrhage can enter the vitreous cavity via the central retinal vessels in the optic nerve. This is known as Terson’s syndrome. Echography is usually ordered because the vitreous hemorrhage obscures ophthalmoscopic evaluation of the retina. Typically, these patients will have varying amounts of vitreous hemorrhage, usually layered over the posterior pole. A thin, shallowly elevated membrane may be seen in the macular region. Many echographers mistakenly call this membrane a localized, shallowly elevated retinal detachment; however, more often than not, this turns out to be a localized partial posterior vitreous detachment (Fig. 4–17). Atta HR, Watson NJ. Echographic diagnosis of advanced Coats’ disease. Eye 1992;6:80–85 Blumenkranz MS, Byrne SF. Standardized echography (ultrasonography) for the detection and characterization of retinal detachment. Ophthalmology 1982;89:821–831 DiBernardo C, Blodi B, Byrne SF. Echographic evaluation of retinal tears in patients with spontaneous vitreous hemorrhage. Arch Ophthalmol 1992;110:511–514 Forster DJ, Cano MR, Green RL, Rao NA. Echographic features of the Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108:1421–1426 Hermsen V. The use of ultrasound in the evaluation of diabetic vitreoretinopathy. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1984;24:125–141 Figure 4–1 Tears. Whenever a patient presents with sudden onset of vitreous hemorrhage and no history of a likely causative systematic disease such as diabetes, small retinal tears must be suspected. (A) Transverse B-scan showing mild vitreous hemorrhage (V) with focal vitreoretinal adhesion and highly reflective tuft of tissue elevated from the fundus (arrow). (B) Longitudinal B-scan showing the peripheral location of the flap tear (arrow). (C) Standardized A-scan; when a tear is large enough or the flap is elevated, a highly reflective spike can be obtained from the area of the tear (arrow). (From DiBernardo C. Ultrasonography. In: Regillo CD, Brown GC, Flynn HW. Vitreoretinal Disease: The Essentials. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1999. Reprinted by permission.) Figure 4–2 Tears. (A) Transverse B-scan showing a treated tear (arrow) overlying a scleral buckle (B). (B) Longitudinal B-scan: Although the tear was treated and a scleral buckling procedure performed, there continued to be persistent retinal detachment. Arrow, tear; B, buckle; R, retinal detachment. Figure 4–3 Tears with retinal detachment. Localized, bullous retinal detachment with retinal tear. (A) Transverse scan showing dense, folded, elevated retinal detachment with a focal area of discontinuity centrally (arrow). (B) Longitudinal scan showing the peripheral location of the tear (arrow). (C) A-scan showing the vitreous cavity (V), the maximally high signal from the retina (arrow) and the bullous nature of the retinal detachment (double arrow). ON, optic nerve. Figure 4–4 Tears, operculum

The Retina

Retinopathy of Prematurity

Retinopathy of Prematurity

Terson’s Syndrome

Terson’s Syndrome

Suggested Readings

Suggested Readings

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree