8 The scrotum and testes

EMBRYOLOGY

Duct system

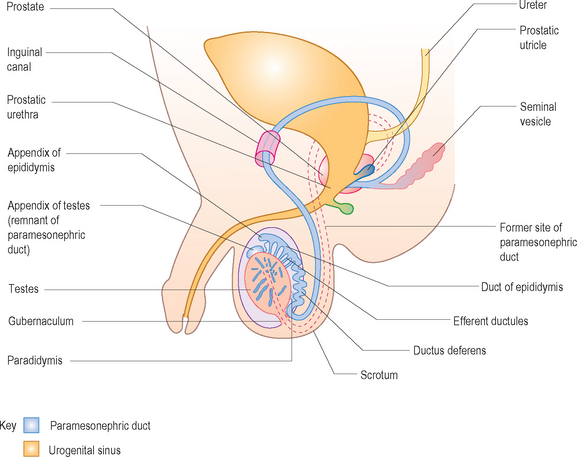

The Sertoli cells of the developing fetal testes produce masculinizing hormones, such as testosterone, which stimulate the mesonephric (old kidney) ducts to form male genital ducts. Some mesonephric tubules persist and are transformed into efferent ductules. These ductules open into the mesonephric duct which has become the ductus epididymis. Just beyond the epididymis the mesonephric duct develops a thick covering of smooth muscle and becomes the ductus deferens. Lateral outgrowths from the caudal end of each mesonephric duct give rise to the seminal vesicles, glands that produce a secretion that provides nourishment for the sperm. The part of the mesonephric duct between the seminal vesicle ducts and the urethra becomes the ejaculatory duct (Fig. 8.1).

Descent of the testes

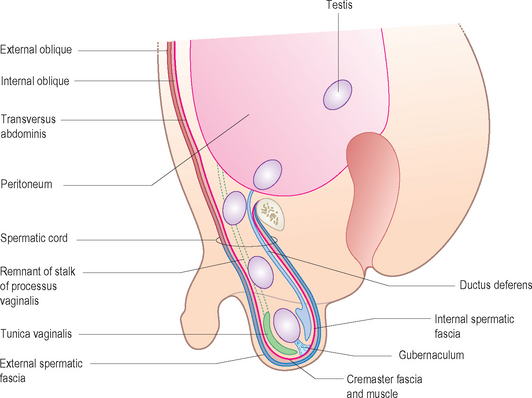

The inguinal canals are the pathways for the testes to descend from their intra-abdominal location through the anterior abdominal wall into the scrotum. A ligament called the gubernaculum is attached at its upper or cranial end to the inferior pole of each gonad. It descends on either side of the abdomen and passes obliquely through the developing anterior abdominal wall at the site of the future inguinal canal (Fig. 8.2). The gubernaculum attaches caudally to the internal surface of the labioscrotal swellings and later serves to anchor the testes in the scrotum. The processus vaginalis is an evagination of the peritoneum and follows the gubernaculum. It herniates through the abdominal wall along the path formed by the gubernaculum and also serves to help guide the testis into the scrotum. The processus vaginalis carries the layers of the abdominal wall before it and goes on to form the walls of the inguinal canal. In males these layers are the coverings of the spermatic cord and testes.

Abnormalities of position of the testis

Ectopic testes

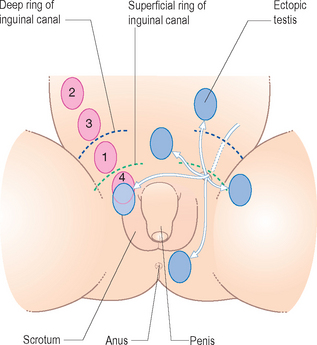

After traversing the inguinal canal, the testes may deviate from their usual path of descent and lodge in various abnormal locations (Fig. 8.3). They may be present in the contralateral scrotum, the perineum, the superficial inguinal pouch, the femoral canal or suprapubically. Ectopic testes occur when a part of the gubernaculum passes to an abnormal location and the testes follow it. Ectopic testes do not have a higher incidence of malignancy but should be placed in a normal position before the age of 2 years.

Hydrocele

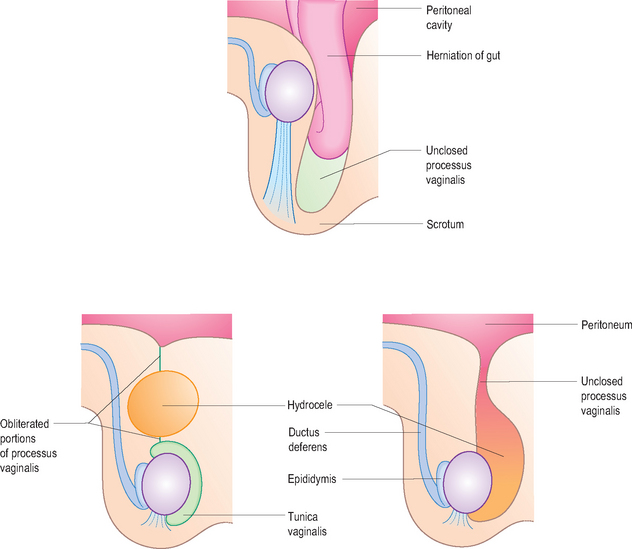

Occasionally the abdominal end of the processus vaginalis remains open but is too small to permit herniation of intestine. Peritoneal fluid passes into the patent processus vaginalis and forms a hydrocele of the testes. If the middle part of the processus vaginalis canal remains open, fluid may accumulate and give rise to a hydrocele of the spermatic cord (Figs 8.4 and 8.5).

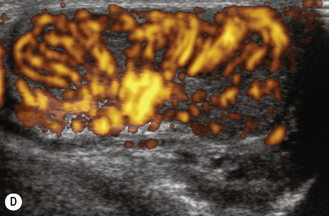

NORMAL ANATOMY

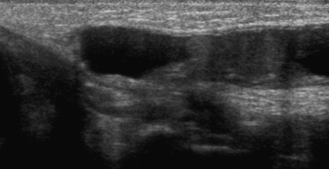

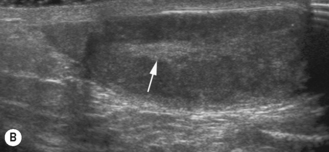

At birth the testes are oval shaped and normally 1.5 cm in length, increasing to 2 cm by the age of 3 months. At adrenarche around about 7 years they slightly increase in size again, and at puberty they again increase in size to measure approximately 3–5 cm in length and 2–3 cm in width. Both sides are normally of similar size. The testis is enclosed in a tough fibrous membrane, the tunica albuginea, which is visible as a linear structure at the mediastinum. The tunica albuginea is not usually identified unless the testis is surrounded by fluid. Fibrous septae divide the testis into lobules centered on the hilum which are also not seen on a normal ultrasound. The 200–300 lobules contain tightly coiled seminiferous tubules. The rete testis is the massing together at the testicular hilum of the seminiferous tubules. The normal testis appears as a homogeneous granular structure of medium echogenicity. The mediastinum testis is seen as a highly echogenic line along the superior–inferior axis of the testis (Fig. 8.6).

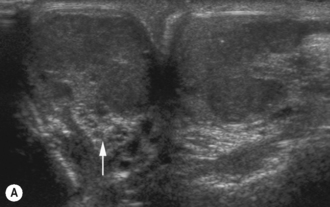

The appendix testis is a testicular appendage which is a remnant of the Müllerian duct (see Fig. 8.1). It is important because it may undergo torsion. Unless there is a hydrocele present, it is not normally identified.

ULTRASOUND TECHNIQUE

The examination is usually carried out with the patient supine. Gel stand-offs are not usually necessary with modern high-resolution transducers. In the young infant the legs should either be in the neutral position or the knees flexed and abducted so the baby is in a frog-legged position to allow better access to the scrotum. In an adolescent boy the sonographer should be sensitive to the patient’s modesty and either perform the examination in a private area or provide sufficient covering with sheets or inco pads so that he does not feel uncomfortably exposed and naked. The young boy should be asked to hold the penis in place over the pubis for better access to the perineum. This is not needed in an infant. If necessary, folded sheets or foam pads can be used for support. If a small scrotal or testicular mass is present, it is best to ask the patient to demonstrate the mass. If the scrotum is tense and tender, care should be taken not to hurt the child.1

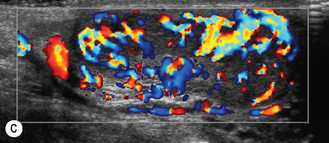

Transducer

The scrotum is best examined with a high-frequency linear 15L8 probe, with the testes being examined in both the longitudinal and transverse planes. If the scrotum is enlarged and swollen so that the testes cannot be fully examined using a linear probe, then a gel stand-off or intravenous saline water bag may be used in order to demonstrate the whole testis. Views of the epididymis can be obtained by scanning obliquely or laterally using the opposite testis as a window. It must be remembered that the scrotal contents are highly mobile, and it may be necessary to hold the testis in position or the technique should be varied according to the image seen.2