10 The wrist and hand

History and examination

Much of what has already been written about the history-taking for the shoulder and elbow also holds true for the wrist and hand: it is part of a kinematic chain and clinical thinking must be directed to the other components of that chain, which may be responsible both for disrupting distal biomechanics and perpetuating symptoms and for referring proximal pathology.1 It is also necessary to be alert for ‘double crush’ mechanisms of neural entrapment: the nerves that pass through the wrist are also subject to entrapment in the elbow, arm and thoracic outlet, which can refer pain or be comorbid with local entrapment.2

Examination of the wrist and hand, perhaps unsurprisingly, reflects that of the ankle and foot, with emphasis on observation; active and passive ranges of motion; neurological assessment; digital palpation; and muscle testing. There is, again, a paucity of meaningful special orthopaedic tests; the one exception to this is Finkelstein’s test for stenosing tenosynovitis of the tendons of extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus.3 This test involves the patient opposing their thumb so that it lies across the palm, then grasping it with the fingers so that it lies within a clenched fist. The examiner then forcibly adducts the thumb to recreate the patient’s symptoms. The examination should also include evaluation of the elbow, shoulder, thoracic outlet and cervical spine.4

The presence of obvious and persistent neurological signs and symptoms would, in the first instance, be likely to precipitate referral for nerve conduction studies; otherwise, diagnostic imaging is the next step for the inconclusive examination or unresponsive patient.5,6

Protocols

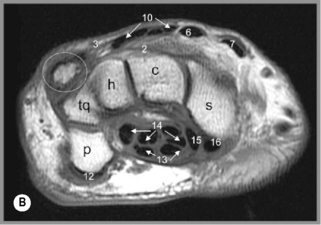

The MR imaging study will normally consist of all three imaging planes: coronal, axial and sagittal, which are normally planned from the axial scout view. T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequences are usually performed in one or more imaging planes, with a slice thickness of 1 to 3 mm being adopted. However, depending on the clinical indication for MR imaging of the wrist and hand, particular sequences or even planes may be selected. In the wrist, the imaging study includes the distal radius and ulna up to the bases of the metacarpal bones. In the hand, the imaging study will normally include the distal carpal row to just beyond the distal aspects of the fingers.7

For either area, contrast may be added, depending on the nature of the clinical situation being investigated. The contrast may be added via the intravenous route, to attempt to differentiate a soft tissue mass or active inflammation8 or, in some institutions, injected directly in to the joint to perform MR arthrography9; however, due to the inherent contrast from the fluid in the wrist, these procedures are not usually necessary. Some institutions have advocated imaging with varying positions of the wrist, placing the patient in pronation and supination in order to further study the ligamentous relationships in these positions10; however, this has not been adopted as standard protocol in most imaging institutions.

Normal and abnormal imaging appearances of the wrist and hand

Osseous structures

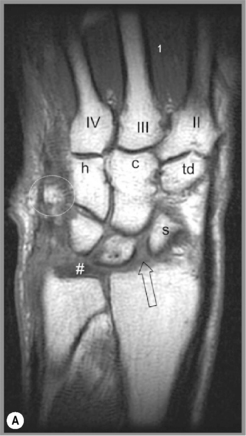

The coronal imaging study will provide information regarding a number of areas, including the overall gross alignment (Figure 10.01, Box 10.01). On these images, the convex head of the ulna and the articular surface of the distal radius should be at the same level; any variance from this can indicate abnormal stresses being placed on the wrist, and is associated with a number of syndromes (Table 10.01).11–15

Table 10.01 Syndromes associated with distal radioulnar misalignment

| Ulna proximal to radius > 2 mm | Radius proximal to ulna > 2 mm |

|---|---|

It is also essential to determine that all the carpal bones are present in the proximal and distal carpal rows (Figure 10.01). Carpal coalition is a condition whereby incomplete segmentation has occurred, resulting in two or more of the carpal bones appearing fused; most commonly, the lunate and triquetrum or the capitate and hamate,16–18 although any adjacent bones may seemingly be involved.19–25 The distal carpals may also be congenitally fused with the metacarpals, the most common coalition being between the second metacarpal and trapezoid.26 Accessory ossicles may be present, which represent a normal variation, usually without clinical consequence to either the patient or physician; one exception to this is the presence of an os styloideum, a common bony protuberance located on the dorsal surface of the base of the second and third metacarpals, which may be associated with degenerative changes, bursitis or ganglia.26,27 In patients with a history of trauma, ossification may occur in and around tendons, resulting in the appearance of osseous lesions about the wrist and hand, a form of myositis ossificans (Figure 10.02).28