Thyroid, Parathyroid, and Neck Ultrasound

Sonography of the thyroid gland is one of the more frustrating areas of US imaging. Expectations are high because sonography is exquisitely sensitive to thyroid abnormalities. Unfortunately, US findings are rarely specific for any disease. Evaluation of thyroid nodules is particularly annoying because thyroid nodules are exceedingly common and US detects most of them, even as small as 1-2 mm, but can rarely unequivocally differentiate benign from malignant nodules. Most of the nodules detected by US are not clinically significant. Fortunately, thyroid cancer is relatively rare; so criteria can be selected to limit the number of biopsies performed and still diagnose the majority of clinically significant cancers. Sonographic guidance is used to direct aspiration biopsy of nonpalpable thyroid nodules and to guide procedures such as alcohol ablation of thyroid lesions [1,2,3].

US is utilized to detect parathyroid adenomas in patients with clinical hyperparathyroidism. These adenomas can then be removed surgically or ablated with US-guided, alcohol injection. Preoperative localization of adenomas decreases operative time and surgical morbidity. Sonography is limited by its inability to detect ectopic parathyroid adenomas in the mediastinum. These lesions may be demonstrated by Tc-99m sestamibi scans, CT or MR [4,5,6].

Masses and adenopathy can be accurately characterized by US, which can also be used to guide aspiration or biopsy.

Imaging Technique

US of the neck is performed with the patient in supine position. The neck is hyperextended by placement of a pillow or folded towels under the patient’s shoulders. A linear array transducer with frequency of 5-10 MHz is utilized. Occasionally, when the thyroid is greatly enlarged, curved-array or sector transducers are used to provide the “big picture.” Images are obtained in transverse and longitudinal planes. The lobes of the thyroid gland and any

focal lesions are measured in three dimensions. Volumes are calculated using the standard formula for volume of an ellipsoid (length × width × height × 0.52). The neck is thoroughly examined for adenopathy. Intrathoracic extension of thyroid disease can be demonstrated by angling the US transducer downward into the mediastinum from a supra-manubrial position. Spectral, color, and power Doppler are utilized to demonstrate the vascularity of the thyroid gland and any focal lesions.

focal lesions are measured in three dimensions. Volumes are calculated using the standard formula for volume of an ellipsoid (length × width × height × 0.52). The neck is thoroughly examined for adenopathy. Intrathoracic extension of thyroid disease can be demonstrated by angling the US transducer downward into the mediastinum from a supra-manubrial position. Spectral, color, and power Doppler are utilized to demonstrate the vascularity of the thyroid gland and any focal lesions.

Anatomy

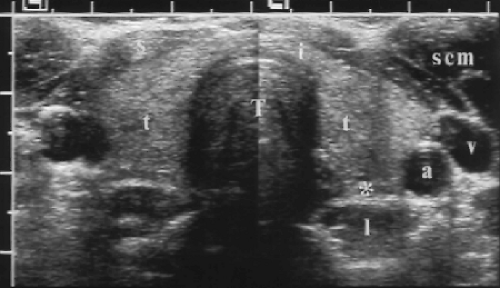

The thyroid gland consists of two ellipsoid lobes connected by an isthmus that extends across the lower cervical trachea (Figs. 9.1, 9.2). Normal thyroid parenchyma is homogeneous and hyperechoic relative to the muscles of the neck. Anatomic landmarks include the common carotid artery (CCA), internal jugular vein (IJV), trachea, and neck muscles. The sternocleidomastoid is seen as an oval muscle mass superficial and lateral to the thyroid. The strap muscles, the sternohyoid, sternothyroid, and omohyoid, appear as thinner muscle bands just superficial to the thyroid. The thyroid extends over the midline trachea between the CCA/IJV vascular bundles. It rests on the prevertebral longus colli muscles. The trachea, being air-filled, causes a bright reflection at its surface and a prominent acoustic shadow. The esophagus commonly extends from behind the tracheal shadow between the left thyroid lobe and the longus colli muscle. The esophagus has a target appearance that must not be mistaken for a thyroid or parathyroid nodule (Fig. 9.3). Identification of the esophagus is confirmed by observing the patient swallow, and observing air or fluid move through the esophagus.

The CCA courses along the lateral aspect of the thyroid lobe, which may partially envelop the CCA when the thyroid is enlarged. The IJV are seen lateral to the CCA.

Enlarged lymph nodes may be detected along the vascular sheath of the CCA/IJV. The thyroid and parathyroid glands are supplied by the superior thyroid artery, a branch of the external carotid artery, and the inferior thyroid artery, a branch of the thyrocervical trunk from the subclavian artery. These arteries (1-2 mm diameter) and their accompanying veins (6-8 mm diameter) course between the thyroid lobes and the longus colli muscles. Spectral Doppler of the thyroidal arteries shows a high systolic velocity (20-40 cm/sec), low resistance (high diastolic velocity) pattern. The thyroid parenchyma shows a richly vascular pattern with power Doppler.

Enlarged lymph nodes may be detected along the vascular sheath of the CCA/IJV. The thyroid and parathyroid glands are supplied by the superior thyroid artery, a branch of the external carotid artery, and the inferior thyroid artery, a branch of the thyrocervical trunk from the subclavian artery. These arteries (1-2 mm diameter) and their accompanying veins (6-8 mm diameter) course between the thyroid lobes and the longus colli muscles. Spectral Doppler of the thyroidal arteries shows a high systolic velocity (20-40 cm/sec), low resistance (high diastolic velocity) pattern. The thyroid parenchyma shows a richly vascular pattern with power Doppler.

Normal parathyroid glands are thin wafers 5 mm in diameter, but only 1 mm in thickness. Normal glands are not visualized by US. US reliably demonstrates adenomas and enlarged glands when they are in the neck. Most patients have four parathyroid glands, although 3% of patients have three glands and 13% have five or more. The paired superior and inferior glands are located deep to the lobes of the thyroid gland and superficial to the longus colli muscle. The inferior glands are ectopically located in the mediastinum in 3% of cases.

Thyroid

Thyroid Nodules

Most thyroid US is requested to evaluate suspected thyroid nodules. Nodules are exceedingly common, with nodules present in 50% of glands normal to palpation on autopsy series and in 18-36% of palpably normal glands on US studies [7,8,9]. Although thyroid cancer is the most common malignancy of the endocrine glands, it remains a rare disease accounting for less than 1% of all malignancy, and is the cause of death in only 0.005% of the United States population [10]. Most thyroid cancers are relatively non-aggressive and have a good prognosis with 90% 10-year survival for early disease. The challenge of US is to differentiate benign from malignant nodules. At this task, US fails because no sonographic finding is pathognomonic. To deal with this dilemma and to avoid a huge number of unproductive biopsies, criteria have been developed to select for biopsy only those patients who are at highest risk for carcinoma.

Malignant Thyroid Nodules

Thyroid carcinoma is 3 times more common in women with median age of 45-50 years at diagnosis. Radiation to the neck, especially in childhood, is a major risk factor, greatest at 20 years after the radiation [11].

Papillary carcinoma is most common (60-70%), is multifocal in 20-80% of cases, and spreads early to regional lymph nodes. The tumor is commonly at least partially cystic and

the lymph node metastases are cystic in 25%. Punctate psammomatous calcifications are a strong sign of malignancy (see Fig. 9.5).

the lymph node metastases are cystic in 25%. Punctate psammomatous calcifications are a strong sign of malignancy (see Fig. 9.5).

Follicular carcinoma (15%) is invasive and spreads more commonly hematogenously to bones and lungs. It is uncommonly multifocal and less frequently spreads to cervical lymph nodes.

Medullary carcinoma (5-10%) may be familial (10% of cases) or associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia. Serum calcitonin is elevated and is a marker of disease.

Anaplastic carcinoma (5%) is exceptionally aggressive with average survival time of 6-12 months. The tumor is locally invasive and spreads rapidly to adjacent structures, nodes (which are commonly necrotic), lungs, and bone.

Metastases to the thyroid (from breast, lung, and renal cell carcinoma and melanoma) may be infiltrative masses or well-defined focal nodules.

Lymphoma accounts for approximately 4% of thyroid malignancy [12]. Older women are most commonly affected. The disease is usually non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hypoechoic nodules grow rapidly and cause dysphagia or dyspnea. Enlarged lymph nodes are seen elsewhere. Cystic change in the enlarged nodes is common.

Benign Thyroid Nodules

Benign thyroid nodules are most commonly adenomatous nodules (adenomatous hyperplasia) or follicular adenomas. True thyroid cysts are exceedingly rare lesions. Most cystic

nodules are cystic degeneration of hyperplastic nodules or adenomas. At least 15-25% of all thyroid nodules have cystic areas within them.

nodules are cystic degeneration of hyperplastic nodules or adenomas. At least 15-25% of all thyroid nodules have cystic areas within them.

Adenomatous nodules are nodules caused by hyperplasia of benign follicular cells. Most often the nodules are multiple. Cystic degeneration, hemorrhage, and calcification are common.

Follicular adenomas are benign neoplasms arising from follicular epithelium. Most are solitary with a well-developed fibrous capsule. Occasionally, adenomas are hyperfunctioning and result in hyperthyroidism with suppression of function of the remainder of the gland. These hyperfunctioning adenomas are “hot” on radionuclide scans.

Biopsy should be considered with the following findings that are associated with increased risk of malignancy:

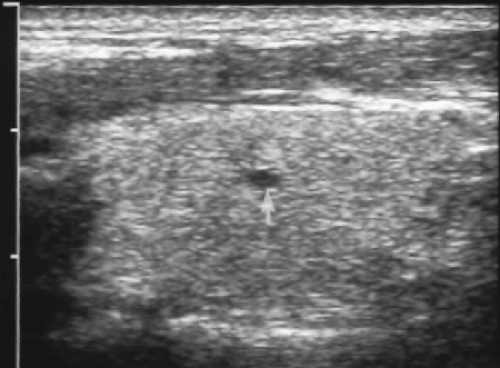

Size >4-5 cm. Large dominant nodules are more likely to be malignant (Fig. 9.4). Few, however, reach size larger than 4 cm before coming to medical attention. Many physicians recommend biopsy of predominantly solid nodules larger than 15 mm.

Psammomatous calcifications. Microcalcifications <1 mm size (Fig. 9.5) scattered throughout a solid nodule are strong evidence of malignancy (70% positive predictive value) [13,14]. The calcifications appear as punctate echodensities. Many are too small to produce acoustic shadows. Psammomatous microcalcifications are strongly associated with papillary carcinoma. The microcalcifications may also be present in lymph node metastases.

Solitary cold nodule on radionuclide scan (Fig. 9.4). The risk of malignancy is approximately 15%.

History of neck irradiation, especially in childhood. The risk is highest at 20 years after radiation exposure and remains high for an additional 20 years [15].

Family history of thyroid malignancy, especially medullary carcinoma.

Age <20 years or male patient with solitary nodule. Benign thyroid nodules are uncommon in children and less common in males.

Irregular contour and poor margination (Fig. 9.4) suggest malignancy but may also be seen with benign nodules.

The following findings are most indicative of a benign lesion that can be followed conservatively or ignored:

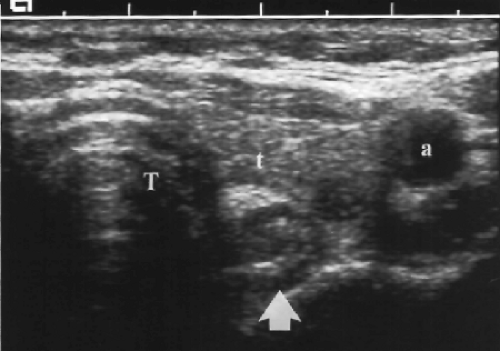

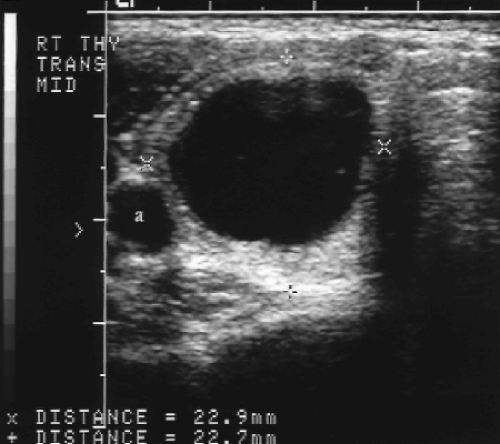

Extensive cystic component is strongly indicative of benignancy (Fig. 9.6). Nearly all of these cystic lesions are the result of cystic degeneration in benign hyperplastic nodules or benign adenomas.

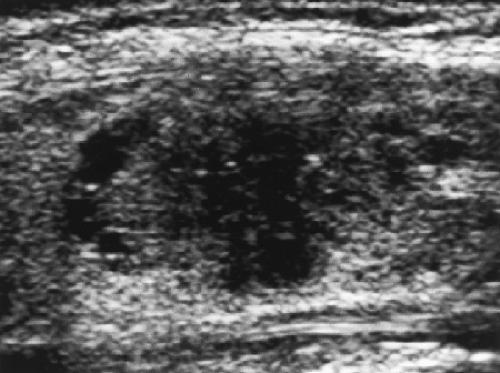

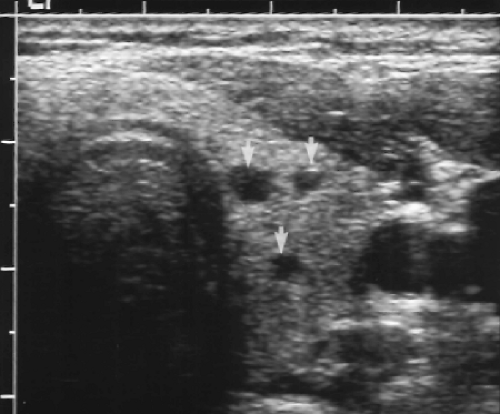

Tiny cysts <5 mm size without an associated solid component are collections of colloid in macrofollicles (Fig. 9.7). These are benign and can be considered a normal finding.

Comet tail artifacts are produced by inspissated colloid [16]. Their presence is indicative of a benign lesion containing abundant colloid.

Homogeneous hyperechoic lesions are rarely malignant. Nearly all malignancies (and most benign nodules) are hypoechoic or isoechoic compared to thyroid parenchyma.

Peripheral rim-like, “eggshell” calcifications (Fig. 9.8) are indicative of a benign lesion.

Increased radionuclide activity, “hot” nodules with suppression of the remainder of the gland are nearly always benign.

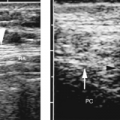

Figure 9.6 Cystic Thyroid Nodule. Calipers (+, x) measure a predominantly cystic nodule in the right thyroid lobe, This is a benign thyroid nodule. Biopsy is not indicated. a, common carotid artery. |

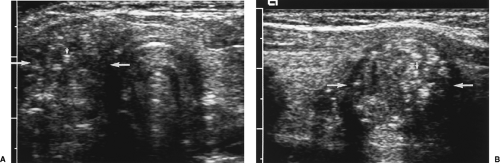

Figure 9.7 Colloid Cysts. Three tiny cysts (arrows) are seen in the left thyroid lobe. The largest of these measures 3 mm. These tiny cysts are normal findings. Biopsy is not indicated. |

The following findings are indeterminate and are found with benign and malignant nodules:

Solid, hypoechoic or isoechoic, nodule (Fig. 9.9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree