Trachea: Developmental Abnormalities

KEY POINTS

- Imaging may make a precise diagnosis in these anomalies but is only adjunctive to the endoscopic examination, with the latter being definitive in the vast majority of cases.

- Imaging might significantly affect medical decision making in some of these developmental conditions.

- Computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging are typically the main and frequently the only studies required aside from a chest x-ray.

Most congenital abnormalities of the trachea will not come to imaging. They will present as airway problems or occasionally neck masses and will be evaluated clinically with direct endoscopy as directed by the clinical setting. These anomalies include those that are mainly structural (but could also be acquired), such as tracheal esophageal clefts and fistulas that may be suspected in the context of other anomalies or syndromes (Figs. 210.1–210.3). Tracheal-related anomalies also include a variety of developmental cysts and vascular malformations that, for the most part, secondarily affect the trachea and only very rarely arise from it (Fig. 210.4). Imaging follows the initial clinical evaluation in selected cases. Imaging usually includes the larynx since subglottic stenosis and laryngeal anomalies will need to be excluded, as they might be associated with tracheal problems and/or produce the same symptoms and clinical problems. For this reason, this chapter should be considered along with Chapter 202 on laryngeal anomalies.

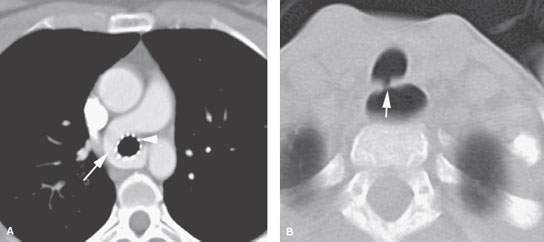

Congenital or early childhood tracheal stenosis or tracheomalacia may arise independent of any identifiable cause; however, it may come to imaging to exclude a mass compressing the trachea or to exclude a tracheal mass (Fig. 210.5). Anomalous vessels associated with congenital heart and great vessel anomalies can cause tracheomalacia (Fig. 210.3A); those conditions are beyond the scope of this text.

In general, developmental abnormalities of the trachea present during childhood. Some manifest in infancy; however, the presentation may be delayed until sometime beyond infancy well into the early adult years and even into middle age (Fig. 210.6). If the lesion has growth potential, it tends to be at the same rate of normal structures, including a possible rapid growth phase at times of accelerated growth of the individual, such as in adolescence. Some, such as high-flow vascular malformations, have internal physiologic dynamics that will allow them to enlarge more rapidly than normal tissues rather than truly proliferate. Truly neoplastic conditions, such as a proliferative hemangioma (Chapters 8 and 9), will manifest growth out of proportion to normal structures; these vascular malformations rarely affect the trachea.

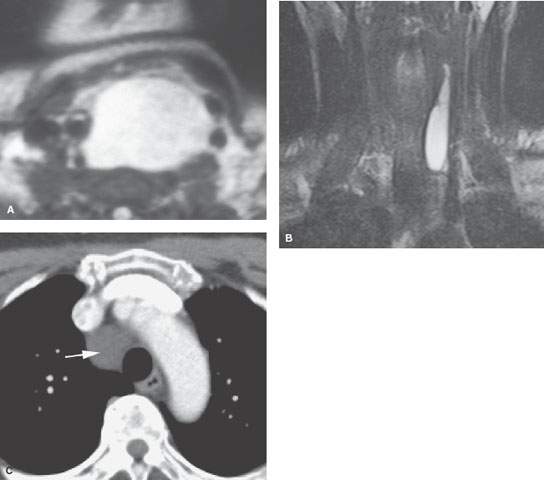

FIGURE 210.1. A patient with multiple congenital anomalies also demonstrating a tracheoesophageal cleft as seen on this contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance image.

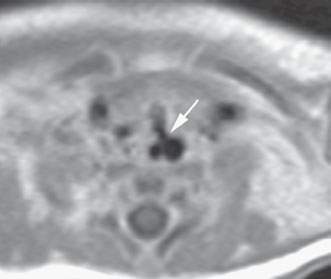

FIGURE 210.2. Computed tomography study of a patient with sleep apnea and noisy respirations. The patient was three years old. A: Contrast enhancement shows what was believed to be a cleft larynx with a very abnormal relationship between the pharynx (arrows) and the laryngeal vestibule (arrowhead). In addition, there appears to be dysmorphic features of the cricoid cartilage (arrowheads) and an unusual relationship between the postcricoid hypopharynx and the cricoid cartilage. B: There is a dysmorphic-appearing larynx, and also there seems to be a minor migrational variation of the thymus appearing as two different migratory cords rather than being more midline in the mediastinum (arrowheads). C: The tracheoesophageal fistula strongly suspected on the imaging study could not be confirmed at endoscopy. (NOTE: More images of this patient are shown in Fig. 202.1.)

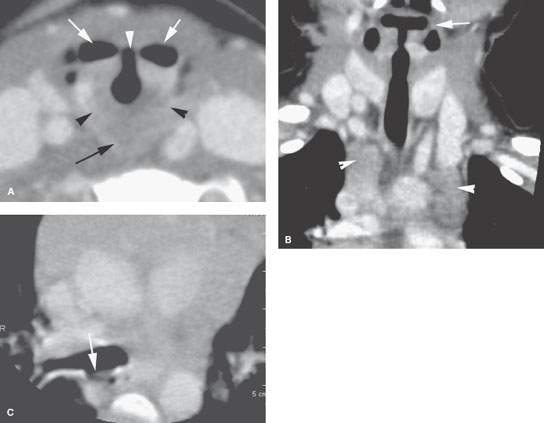

FIGURE 210.3. Two patients with tracheal problems associated with other anomalies or syndromes. A: Patient 1 with a pulmonary sling (arrow) that caused tracheomalacia requiring stenting (arrowhead) to avoid a vascular fistula and lower airway dysfunction. B: Patient 2 with Goldenhar syndrome. A computed tomography study shows a tracheoesophageal fistula that was not suspected but did finally explain why the patient coughed every time he ate.

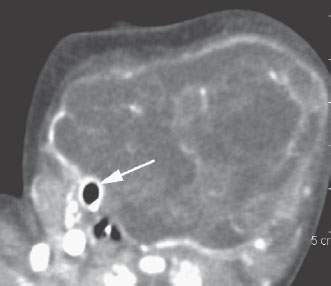

FIGURE 210.4. Three patients with developmental cysts. None were subsequently proven to involve the trachea. Two of the cysts displaced and compressed the trachea with the potential to result in tracheal malacia. A: Patient 1. T2-weighted (T2W) image of an esophageal duplication cyst. B: Patient 2. A pediatric patient presenting with a vague palpable mass in the neck. This cyst was identified. The exact nature of the developmental cyst was uncertain based on the imaging origin from the trachea, esophagus, or foregut for a cyst of thymic migration. Surgery showed this to be a thymic cyst. C: Patient 3. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of a bronchogenic cyst involving the upper mediastinum. D, E: CT study of a cystic midline neck mass that could be either of thymic or bronchogenic origin. Bronchogenic cysts typically are more closely related to the trachea and/or have a mediastinal component. F: Contrast-enhanced CT of an infected third or fourth branchial apparatus cyst. Even with the very intense secondary infection, the congenital cyst only has a relatively minor effect on the trachea, displacing but not compressing that structure. (NOTE: Bronchogenic cysts of the neck are rare and cannot be distinguished with certainty from the equally rare cervical thymic and parathyroid cysts. The distinction is really not very important since the surgery is essentially the same, with the specific approach based on the extent of the mass as seen at imaging.) G–I: A 24-year-old woman with an enlarging neck mass. T2W (G) axial and T1-weighted (H) fat-suppressed images show the mass to be cystic and displacing and compressing the trachea (arrow) but not arising from it or the esophagus (arrowhead in H). I: T1W fat-suppressed sagittal image showing the mediastinal component (arrow) in contact with hyperplastic thymic tissue. This proved to be a parathyroid cyst. (NOTE: The differential diagnosis included bronchogenic cyst, thymic cyst, foregut duplication cyst, and parathyroid cyst as well as lymphangioma. Thyroid cysts do not attain this size.)

Developmental abnormalities may be discovered incidentally on imaging studies done for other purposes (Figs. 210.3B, 210.4C, and 210.7), but they more typically present as a neck mass or because they interfere with airway function, producing noisy breathing or, in an infant, sleep apnea. These are all rare occurrences except for tracheoceles, which are seen incidentally in a fraction of a percent of the population that come to imaging for other reasons (Fig. 210.7). They are typically not painful unless there is some present complicating factor. Developmental abnormalities may also manifest because of such complicating factors. Examples include infection in a cyst or diverticulum that connects to the trachea and bleeding, thrombosis, or infection of a vascular malformation.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Embryology

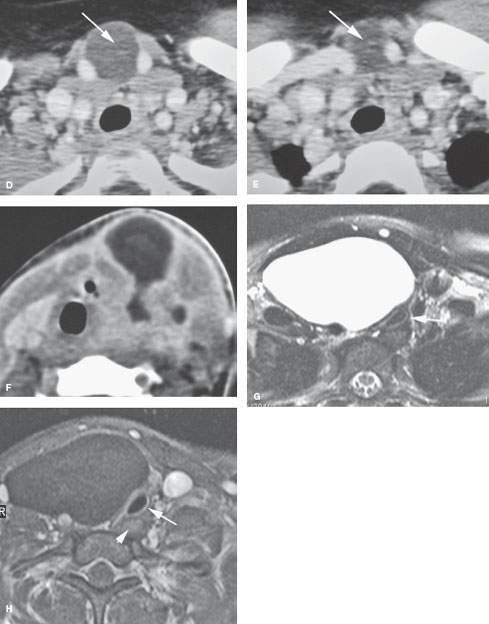

FIGURE 210.5. A cervicothoracic teratoma, the origin of which is uncertain. The trachea was essentially completely occluded by the mass. The endotracheal tube is the only visible evidence of the trachea on this study.

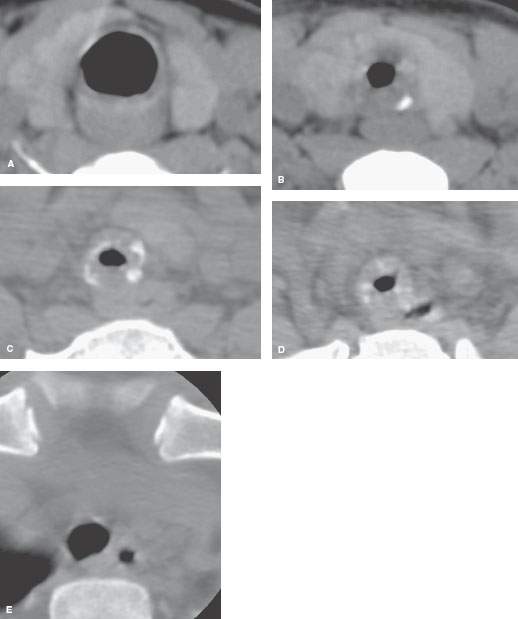

FIGURE 210.6. A pediatric patient with a long history of exertional dyspnea and wheezing. There was no history of intubation. A computed tomography study was done. A: A section at the level of the cricoid ring showing it to be essentially normal. B–D: A two-segment dysmorphic trachea with narrowing of the airway to well under 25% of its usual cross-sectional area. The tracheal rings are dysmorphic. E: The trachea returned to a more normal appearance at the thoracic inlet. Since there was no history of trauma, infection, or intubation, this was considered to be a short segment congenital tracheal stenosis due to tracheal ring dysplasia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree