Renal Transplant Surgery

Introduction

Renal transplantation is the preferred treatment for selected patients requiring renal replacement therapy. Patients with successful renal transplants enjoy improved quality of life,1 may live longer than patients undergoing dialysis awaiting transplantation,2 and can reduce health provision expenditure when other renal replacement therapy is discontinued.3

In the war against early and late graft dysfunction, ul-trasonography is invaluable in the diagnosis of ureteric outflow obstruction and perinephric collection, whilst color Doppler ultrasonography is helpful in the diagnosis of diminished or abnormal arterial perfusion, venous outflow obstruction, and a wide range of other abnormalities which may lead to graft failure. As an ultrasound examination is noninvasive, serial Doppler ultrasound studies of transplanted renal grafts have become routine and are incorporated into many units’ standard patient follow-up protocols.

Summary point:

Summary point:

- Renal transplantation is the preferred treatment for patients requiring renal replacement therapy.

Donor Kidney

The blood supply to the developing kidney comes from the great vessels, which lie in close proximity to the kidneys during embryological growth. Initially, early in development, the kidneys lie in the pelvis, but as the embryo grows they are seen to migrate such that they occupy progressively higher positions within the abdomen. To begin with, the renal blood supply is derived from branches of the middle sacral and common iliac arteries. As the kidneys ascend, the blood supply originates from sequential arteries extending from the lateral aspect of the elongating aorta, until, in most individuals, definitive single renal arteries supplying all of the kidney and the first 10-15 cm of the ureter form just adjacent to the superior mesenteric orifice. It is not surprising however, that 25% of kidneys are found to have multiple renal arteries, a variation which reflects the manner in which the blood supply continually changes during the ascent from the pelvis to the abdomen. A single lower polar accessory vessel supplying up to 40% of the lower kidney and the first 10-15 cm of the ureter, or a single upper polar accessory vessel supplying less than 10% of the upper pole of the kidney are the most common of the polar variants. Dual and triple polar variations, however, are also encountered.

Usually, when cadaveric renal grafts are used for transplantation, polar vessels are left on the aortic patch so that only one arterial anastomosis is fashioned during the transplant operation. In some circumstances, however, this may not always be possible, because as part of the bench work to clear the kidney of unwanted fat prior to transplantation, accessory vessels may need to be reconstructed onto the main renal artery or the aortic patch trimmed and re-sutured. Unfortunately, reconstruction procedures increase the likelihood of a postoperative arterial complication, and when lower polar variants are encountered, a complication of thrombosis of the accessory artery may lead to both renal infarction and ureteric necrosis.

Transplant Procedure

Transplant Wound

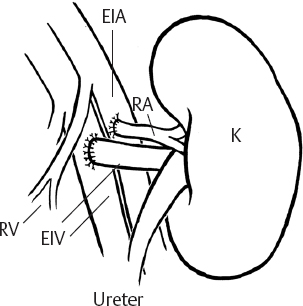

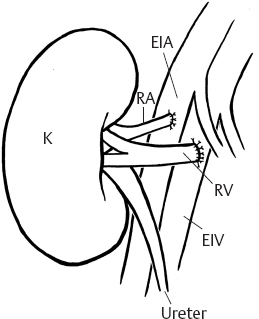

The side chosen to transplant on may ultimately be decided because of the presence of a previous transplant graft or asymmetry in peripheral vascular or polycystic kidney disease, but a few other factors should also be considered at the time of transplantation. With the renal vein entering the kidney superficial to the artery in the coronal plane, a right or left kidney when transplanted into the contralateral iliac fossa with the lower pole placed caudally requires the artery and vein to be crossed when the anastomoses are fashioned using the external iliac vessels (Fig. 3.1). This is usually not problematic, but can be easily avoided if the transplant is carried out on the side that the kidney was removed from (Fig. 3.2). However, if the internal iliac artery is used for the arterial anastomosis, as is commonly preferred when live donor kidneys are used, the artery and vein do not cross when situated in the contralateral iliac fossa (Fig. 3.3). It is interesting to note that when renal transplantation was evolving, the internal iliac artery was used in preference to the external iliac artery, and it became conventional and incorporated into surgical dogma that kidneys should always be placed on the con-tralateral side!