Routine:

Skull: anteroposterior (AP) and lateral

Lateral skull (may include C-spine)

Lateral thoracic and lumbar spine

Ribs: AP, right posterior oblique, left posterior oblique

AP pelvis and lumbar spine

AP of each femur

AP of each tibia/fibula

AP of each humerus

AP of each forearm

Posteroanterior of each hand

AP (dorsoventral) of each foot

Optional:

Lateral views long bones

Coned views of joints or ribs

Townes view of skull

Ideally, images are reviewed by a radiologist versed in the imaging findings of child abuse and its differential diagnosis before the child leaves the imaging room. Radio — graphs are checked for image quality, proper positioning and labeling. The radiologist should verify that the study contains all the required views. Additional images can be obtained to further evaluate equivocal findings and positive findings. Most commonly, this would entail addition of lateral views of the long bones or lateral views centered at the joints. A Townes view of the skull can be obtained to better evaluate the occipital bone and to look for wormian bones, particularly if fractures are found elsewhere in the body.

In equivocal cases or in cases where there is a very high clinical suspicion for child abuse but the initial skeletal survey is negative, a follow-up skeletal survey or nuclear medicine bone scintigraphy can be helpful [5]. A follow-up skeletal survey is typically obtained 10–14 days after the initial survey and may be limited to the long bones and ribs, also including other areas of radiologic or clinical concern from the time of the initial survey. Most centers use nuclear medicine bone scans sparingly; however, they can be very sensitive for certain fractures, such as of the ribs.

Imaging obtained for evaluation of central nervous system or visceral trauma should be carefully evaluated for osseous findings. For instance, rib fractures can be evident on chest or abdominal radiographs, on the upper images of abdominal computed tomography (CT) or on CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine. Head CT images should be carefully evaluated for skull fracture. While some authors have proposed whole body CT, its use is limited by radiation dose and lower spatial resolution than radiographs. Nonetheless, focused CT can be helpful in confirming rib fractures. Whole body MRI is of limited use in detecting lesions that are relatively advanced in healing [6].

Radiographic investigation is strongly indicated for all fatal cases of suspected child abuse as well as for all unexpected infant deaths [7]. A postmortem skeletal survey is performed with the same technique as in the living child. In the postmortem state, where radiation dose is no longer a concern, CT parameters can be changed to increase resolution. At this time, however, the utility of CT for postmortem evaluation is still under investigation [8].

Specificity of Findings

Through the seminal work of Dr Paul Kleinman, and supplemented by others, the individual radiographic findings of child abuse can be characterized into high specificity, moderate specificity and low specificity (Box 2) [9, 10].

Box 2

Specificity of radiographic findings for child abuse*

High specificity | Posterior rib fracture |

Classic metaphyseal lesion (CML) | |

Scapular fracture | |

Sternal fracture | |

Spinous process fracture | |

First rib fracture | |

Moderate specificity | Multiple fractures |

Fractures of differing age | |

Complex skull fracture | |

Spine fracture | |

Physeal fracture | |

Digital fracture | |

Low specificity | Periosteal new bone formation |

Long bone diaphyseal fracture | |

Simple skull fracture | |

Clavicle fracture |

High-Specificity Findings

Posterior Rib Fractures

Rib fractures caused by accidental trauma are uncommon in children under 5 years of age because of the plasticity of their bones. As such, any rib fracture in a child without reliably witnessed trauma and without metabolic bone disease must be viewed with a degree of suspicion. Rib fractures can occur at any location in the rib arc. Acute transverse fractures with displacement are rare. Acute fractures are usually greenstick or buckle fractures and can be very difficult to see on radiographs, if at all. Particularly if lateral, there may be associated subpleural hematoma. Posterior rib fractures, near the spine, have the highest specificity for child abuse [9, 11]. The rib is torqued or levered over the transverse process. Posterior rib fractures become more conspicuous with callous due to healing. Frequently, fractures of the lateral rib arc are seen in conjunction with posterior rib fractures (Fig. 1). These lateral rib fractures also occur with squeezing due to a compressive force on the inside arc of the rib and a distractive force on the outside arc of the rib. Oblique views aid in detection of rib fractures (Fig. 2) [12]. Differential considerations: rib anomalies, fractures due to metabolic disease, superimposition of sternal ossification centers, normal anterior flaring of the ribs.

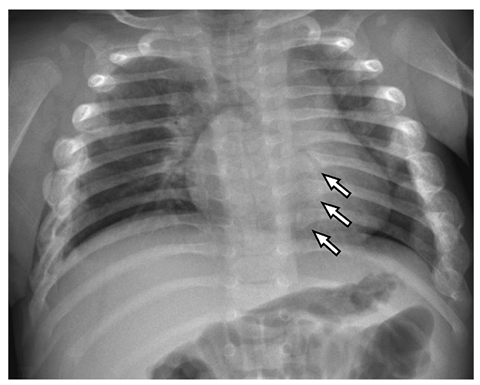

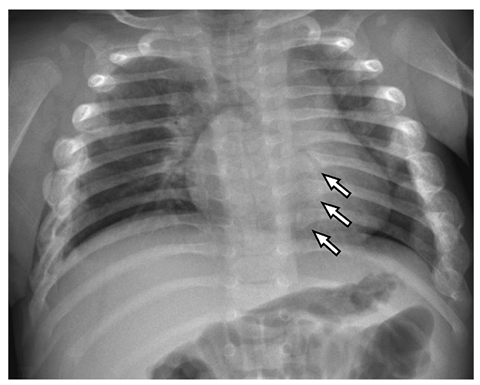

Fig. 1

Multiple healing rib fractures in a 10-week-old asymptomatic boy whose twin was fatally abused. The right third to ninth and left fourth to ninth ribs are expanded laterally with callous. In addition, there are subtle healing fractures of the posterior left seventh to ninth ribs (arrows)

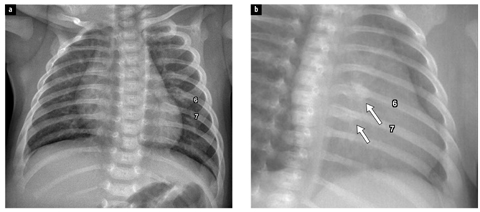

Fig. 2 a, b

Healing posterior rib fractures in a 6-week-old boy: a anteroposterior and b oblique views. The oblique view aids in identification of fractures of the left posterior sixth (6) and seventh (7) ribs (arrows)

Fracture of the First Rib

Although rare in child abuse, fracture of the first rib in an infant is generally not seen as a result of other causes (Fig. 3). These fractures are likely to occur as a result of indirect forces related to shaking or rapid flexion with the scalene muscles attached to the body of the first rib and its ends fixed by the manubrium anteriorly and the spine posteriorly [13]. Differential considerations: first rib anomaly, anomalous articulation of first and second ribs.

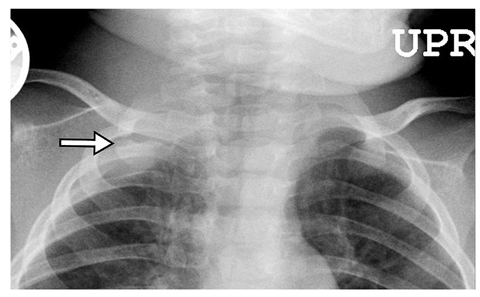

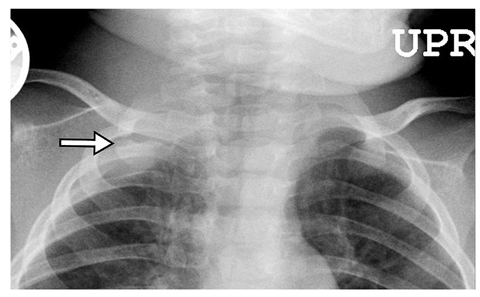

Fig. 3

Acute first rib fracture in a 3-month-old boy. The fracture line (arrow) is sharply defined with slight distraction of fragments. There is associated subpleural hematoma

Fractures of the Sternum, Scapula and Spinous Processes

Fractures at these sites are also rare in child abuse, but generally not seen from other causes. Specific applied forces in child abuse can predispose to these fractures. Possible mechanisms include blunt force from anterior causing sternal fracture, direct force due to the grasp of an abuser causing acromial fractures, and forced flexion due to shaking or axial impact causing spinous process fractures. Differential considerations: normal sternal ossification centers, acromial variants.

Classic Metaphyseal Lesions

The term “classic metaphyseal lesion” (CML) was introduced by Kleinman to include “bucket handle fracture” and “corner fracture” type lesions of the metaphyses of long bones [9, 14]. The lesions are relatively transverse fractures through the edge of the metaphysis. Depending on the degree of displacement, the position of the limb and the angle of the X-ray beam, the acute lesion can appear as either a curvilinear fragment (“bucket handle”) or as a corner fragment (Fig. 4). With healing, lesions become indistinct, there is associated sclerosis, cartilaginous ingrowth into the metaphysis can occur, and the lesion disappears [15]. Periosteal new bone formation is seen with healing only if there is associated periosteal injury. In rough decreasing order, CMLs are most common at the distal tibia and fibula, the distal femur, the proximal tibia and fibula, the distal radius and ulna, and the proximal humerus. They are uncommon at the proximal femur and at the elbow. CMLs probably occur as a result of torsional force applied to a limb or extreme forces experienced with shaking with the extremities flailing. Differential considerations: normal developmental variants [16], pyhysiologic bowing, rickets, (spondylo)metaphyseal dysplasia especially types Schmid and Sutcliffe (“corner fracture type”), congenital syphilis, Menke syndrome, scurvy.

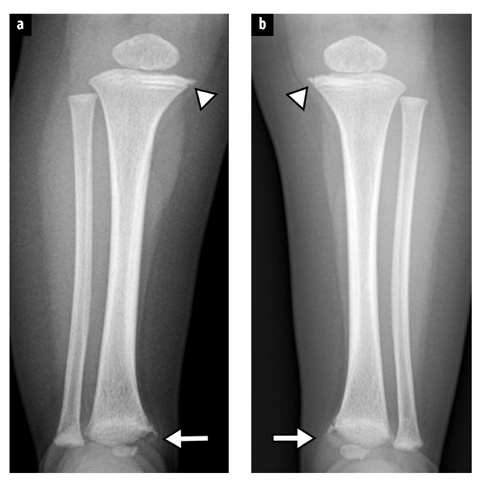

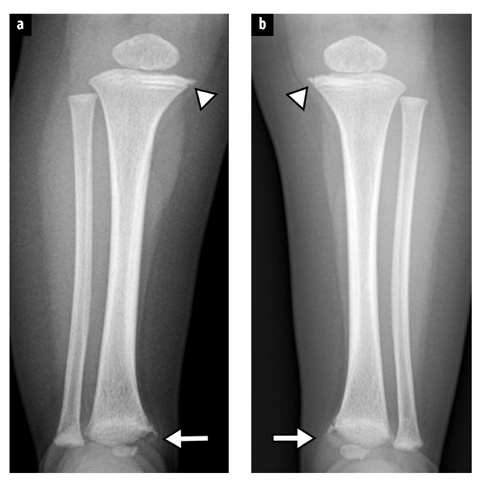

Fig. 4 a, b.

Classic metaphyseal lesions in an 8-month-old girl. a Right tibia. b Left tibia. Bucket handle fractures are seen at each distal tibia (arrows). Subtle corner fractures are seen at the medial aspect of each proximal tibia (arrowheads)

Moderate-Specificity Findings

Multiple Fractures and Fractures of Differing Age

While most think of multiple fractures and fractures of differing age as characteristic of abusive injury, these findings are only moderately specific. Children with metabolic bone disease and children with certain syndromes, namely osteogenesis imperfecta, are prone to fracture and can have multiple fractures and fractures of differing age. Almost uniformly, such children have a known medical history, radiography suggests an underlying bone disorder, and the fractures seen do not fall into the high-specificity patterns describe above. An otherwise well child with normal bone mineralization with multiple fractures of differing age presenting to an emergency room should promptly raise suspicion for child abuse. Differential considerations: metabolic bone disease including rickets, osteogenesis imperfecta, Menke syndrome, multiple episodes of accidental trauma.

Spine fracture

Infants can suffer spinal trauma as a result of axial or direct impact or extreme degrees of flexion. Compression fractures are most common in the lower thoracic and upper lumbar spine, but may occur throughout the spine [17]. Critical cervical spine trauma and spinal cord injury are uncommon, but may occur. Differential considerations: vertebral anomalies including hypoplasia, infection, neoplasm.

Growth Plate Fractures

Fractures through the growth plate (physis) in the infant are uncommon [18]. These fractures can occur due to other causes, namely birth trauma. Physeal fractures caused by abuse are most common at the proximal humerus (Fig. 5), perhaps related to the grasp of the abuser’s hands. Interestingly, these fractures seem to be more common in children aged 2–3 years. Less common sites of abusive physeal fracture occur at the proximal femur and the distal humerus. Differential considerations: birth trauma, infection.