Fig. 15.1

Progress in flow ultrasound imaging may soon provide a contrast enhancement effect (on the right) without using any injected contrast agent; tumor (T); glissonian pedicle (GP); hepatic vein (HV)

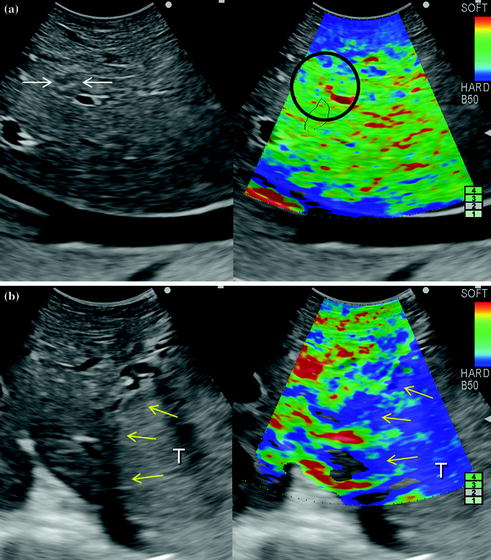

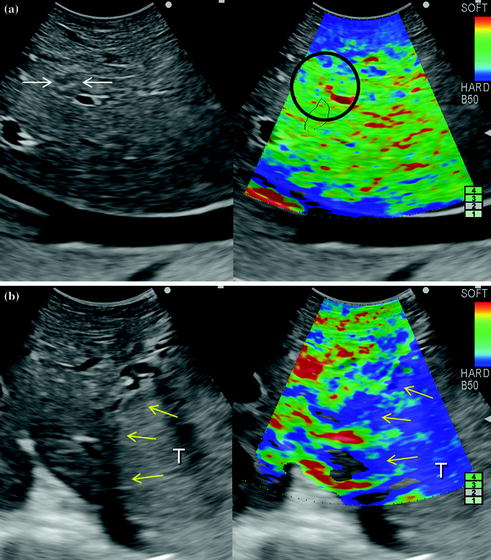

In the short term, one can expect the further spread of a combination of IOUS with such new technologies as fluorescent imaging, providing more crucial information for disease staging. Also, elastography has attracted the interest of many physicians for its potential in differentiating lesions based on their stiffness (Fig. 15.2a, b).

Fig. 15.2

a Based on the color scale on the upper right of the picture (soft is red and hard is blue) a hemangioma (arrows) as already seen in Chap. 4 almost remains invisible compared to the surrounding parenchyma (black circle) once elastography is activated; b inversely, the margins of a hepatocellular carcinoma (yellow arrows) grossly correspond with the blue area at elastography, meaning an increased stiffness compared to the surrounding parenchyma; tumor (T)

15.2 Surgical Strategy and Resection Guidance

Elastography may become beneficial not only for lesion differentiation but also may provide real-time information to help in defining the surgical strategy in terms of entity of parenchymal removal. It can be applied to evaluate liver stiffness intraoperatively, as the relation between the latter and the hepatic functional reserve are relevant in predicting the surgical risk [1, 2]. Preoperative evaluation together with elastography can add further information in defining the surgical strategy, allowing a more conservative operation in case the stiffness was preoperatively underestimated.

Further technical developments and dissemination of the navigation systems are also to be expected. However, they currently remain costly and feature a complex “plug and play”, which limits their wide-spread use and, accordingly, their clinical relevance. New ultrasound systems, which can match in real time the preoperative imaging of CT and MRI with IOUS will improve intraoperative navigation modalities providing more simple and low-cost solutions than those currently proposed (Fig. 15.3a, b). They facilitate the interpretation of ultrasound images and thus the planning of the surgical strategy. Navigation with matched preoperative imaging will help to improve the detection of lesions otherwise not well visible by IOUS, as isoechoic lesions (Fig. 15.4). Similarly, navigation with matched imaging done prior to medical treatment will probably guide removal of those CLMs having disappeared after chemotherapy.

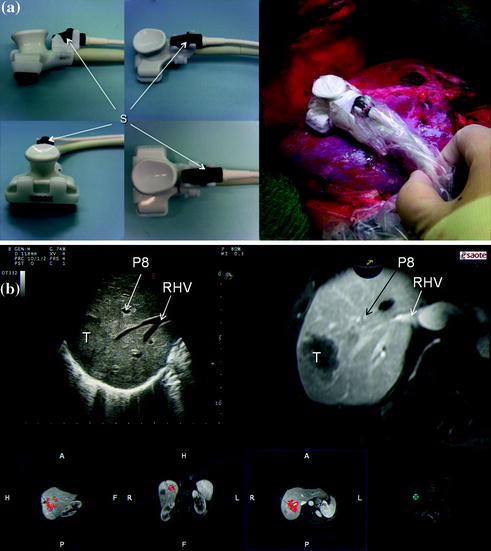

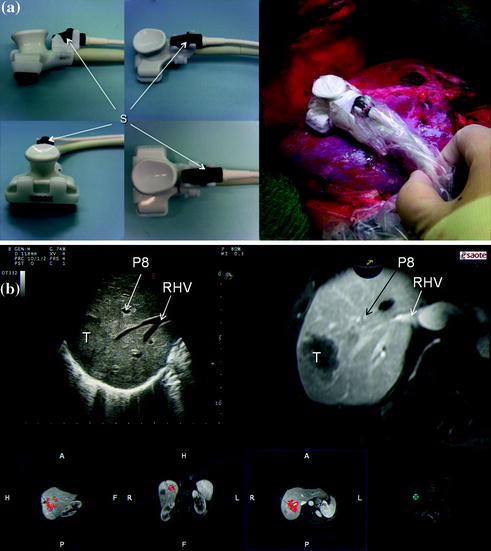

Fig. 15.3

a Ultrasound navigation using dedicated sensors (S) to read the movement of the probe; b combination of the ultrasound image with those of the computed tomography (CT) or the magnetic resonance (MRI) which are elaborated to reproduce exactly the ultrasound scan: this may facilitate the reading of the IOUS image while exploring the liver; portal branch to segment 8 (P8); right hepatic vein (RHV); tumor (T)

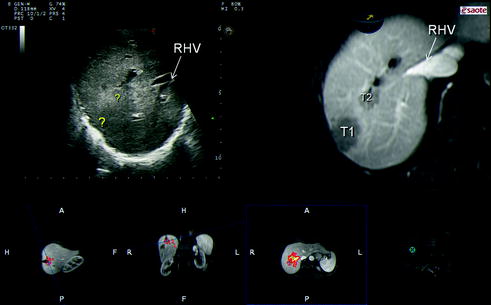

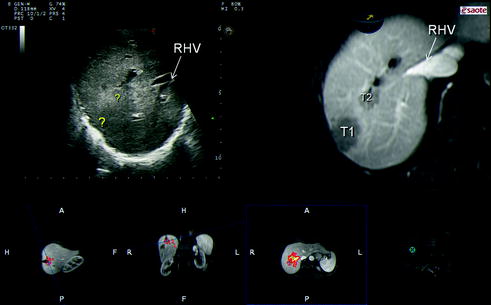

Fig. 15.4

Ultrasound navigation can be useful in disclosing lesions which are not well visible by IOUS, such as those that disappear after chemotherapy (combining the imaging done before chemotherapy) or that are isoechoic at intraoperative exploration (?) but well visible in preoperative imaging (T1, T2), for which the margin disclosure is helpful for defining the surgical strategy; right hepatic vein (RHV)

Such potential advancement can improve the role of IOUS guidance during liver resection. As described in this monograph, the aim is to guarantee, wherever possible, both anatomical and limited resection with a radical intent: this is relevant both for the effectiveness of the surgical treatment as for its safety. Without IOUS guidance, operations may involve useless major resections or inversely could result in incomplete tumor removal. The techniques of liver resection based on ultrasound guidance as herein extensively described show that for selected patients it is possible to closely approach the tumor burden without increasing the risk of incomplete removal or local recurrence [3]. Therefore, new oncological concepts are introduced. For HCC, tumor exposure on the cut surface does not contradict a full anatomical resection with respect to the oncological requirements for this kind of tumor [4], and this has been confirmed through several cases [5–7]. For CLM, getting closer to the tumor burden under IOUS guidance, even exposing it, is not in contradiction with a concept of radical surgery, at least not in cases that are not amenable by other approaches. Indeed, there is no increase in the risk of local recurrence and similar survival rates are observed [8–12].

An additional point of view in surgical practice introduced by IOUS consists in a new management concept of carriers of tumors that are at risk of compromised liver outflow. CFIOUS enables the disclosure of anatomical features otherwise not recognizable, such as the communicating veins [13], and has opened up new technical solutions allowing the introduction of new operation procedures [14–16]. This allows a more conservative approach to conditions that previously required major resections, complex and at-risk vascular reconstructions, or were even unsuitable for surgery. Further improvement of CFIOUS technology and the combination of IOUS with such new tools as fluorescent imaging can improve the information level. Also, the relation between degree of congestion and liver function based on fluorescence imaging during liver transplantions may allow new scenarios by having available additional criteria for establishing whether intraoperatively detected communicating veins are sufficiently functional to decide whether to vicariate the hepatic vein to be resected or not.

This means that, with IOUS guidance it is possible to perform conservative but radical hepatectomies, and then to expand the surgical indications. With this approach the rate of major hepatectomies has been limited to 8 % in patients with tumors involving one or more hepatic veins close to their caval confluence, without performing any related vascular reconstruction [17], and to 4 % in patients with mutiple bilobar CLM with removal of up to 49 lesions at once [9]. Limitation of major hepatectomy has also been applied to advanced HCC, with less than 1 % mortality and improved long-term outcome [5]. Because this approach reduces the rate of major hepatectomies, the need for interventions such as preoperative PVE, adopted to prevent liver failure after major removal of liver parenchyma could be drastically reduced [18].

Therefore, in spite of the need for large exposure of the organ, IOUS-guided liver surgery should be considered a minimal invasive procedure having as main target just the sparing of the liver parenchyma, and its absolute safety is paradigmatic of what has been just affirmed: organ-targeted minimal invasion. Mostly because of that, surgery is still considered the treatment of choice for the majority of liver tumors in spite of the development and progress in other local treatments such as ablation therapies and intravascular procedures. Furthermore, the use of IOUS for expanding the indications for tumor removal, paradoxically, is in opposite trend with the introduction of ultrasound itself for guiding intraoperative tumor ablation. As a matter of fact, stressing the use of IOUS for guidance, it is possible to expand the surgical indications for HCC and CLM without recurring in any case to ablation treatment [5, 9]; the latter being certainly less radical than tumor removal [19, 20].

15.2.1 Laparoscopic Approach

Liver resections as discussed in the preceding chapters allow the combination of broad indications with a high level of safety, while they do demand large incisions with extensive mobilization and complex dissection plans. These requirements are opposite to the background motivating the anterior approach with or without a hanging maneuver [21, 22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree