TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA AND OTHER TRIGEMINAL NEUROPATHIES

- Magnetic resonance, sometimes including magnetic resonance angiography, is the primary tool when looking for a structural cause for a trigeminal neuropathy of any segment of its distribution with the exception of lesions that are arising in or primarily manifest in bone.

- Computed tomography may be used if the pathology likely localizes to the sinonasal region or manifests primarily in bone.

- Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance angiography cannot be trusted to confidently exclude all conditions that may lead to a trigeminal neuropathy.

- The causative pathology may be of the end organ or other structures innervated by the nerve rather than the nerve itself.

- Diagnostic imaging, even performed optimally, fails to find a reason for these neuropathies in many patients, and if the symptoms and signs are progressive and/or an additional cranial nerve deficit emerges, imaging should be repeated.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical Presentation

The trigeminal nerve will typically dominate the clinical presentation as in typical trigeminal neuralgia. Sometimes, one or more of cranial nerves (CNs) II, III, IV, and/or VI will be involved following careful clinical testing. When more than one nerve is affected, and possibly associated with other symptoms or neurologic deficits, localization may be much easier and a very “directed” and concise imaging evaluation is possible. Most clinical situations require a comprehensive imaging study of the entire brain and sinonasal and facial region.

Sometimes, lesions outside the expected course of the nerves or involving end “organ” sites of sensory trigeminal nerve supply, such as sinus or dental disease, will be the source of symptoms. It is critical to understand all of the neurologic deficits and complaints that might arise from the trigeminal nerve to enable effective imaging and interpretation of the images.

Clinical presentations that may involve the trigeminal nerve can be reasonably grouped as suggested subsequently. It is important to keep in mind the clinical contexts that will be suggested. Just as important is an orderly, segmental approach in the search for responsible structural pathology. This approach ensures that the planning and interpretation of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or computed tomography (CT) studies for these problems will have the highest possible yield of information to help care for these often chronically ill and sometimes incapacitated patients.

The symptoms can be disabling and confusing as to origin. They are frequently wrapped up with symptoms that are thought to be either migraine or tension pattern headaches when the pain is atypical. Progressive symptoms, especially when an atypical pattern of trigeminal neuralgia is present, require a careful and sometimes repeated imaging search for a structural lesion.

Typical Trigeminal Neuralgia (Tic Delaroux)

Typical trigeminal neuralgia is almost unmistakable clinically. It will produce intermittent lancinating pain in any division of the trigeminal nerve, more commonly the second and third. There will often be a touch-sensitive triggering event such as shaving. The pain pattern is chronic but not usually inexorably progressive, although it may vary in duration and frequency.

Atypical Facial Pain

Atypical facial pain is any pain other than trigeminal neuralgia. It will not necessarily have a distribution in a dermatome of a particular division of the trigeminal nerve. It may actually be a headache and, if associated with autonomic dysfunction, be a migraine variant. It may have an “end organ” origin such as the sinuses, teeth, or temporomandibular joint (TMJ). If atypical facial pain is progressive in severity and/or distribution, it is reasonable and almost mandatory to image for a possible cause unless there are mitigating clinical circumstances.

Progressive Sensory Dysfunction of a Single Division

Numbness and tingling or formications in one or more of the trigeminal nerve dermatomes is a very important symptom even if a neurologic deficit cannot be absolutely confirmed by a careful sensory examination. If progressive, the situation is often serious and suggests a possible perineural pathology such as might be caused by a skin cancer removed in the remote past that has recurred entirely subcutaneously as perineural spread (Chapters 21 and 24). The patient sometimes does not recall such prior treatment. Progressive disease in this situation almost mandates highly focused imaging of the peripheral and central pathways of the trigeminal nerve. If imaging is negative and the symptoms progress, then repeat imaging is a very reasonable course of action especially if the patient has a history of treated skin cancer of the facial region.

Motor Dysfunction

It is unusual for the trigeminal nerve to present as a motor deficit. This can manifest as a jaw dysfunction or facial asymmetry due to wasting of the muscles of the masticator space and scalp (temporalis). This can also be seen as mononeuropathy of the V3 due to perineural spread of skin or other cancer that might be otherwise clinically “occult” (Chapters 21 and 24).

Segmental Approach to Trigeminal Nerve Dysfunction

Brain Stem and Cisternal Segments

Brain stem and extra-axial lesions in the upper cerebellopontine angle and lower perimesencephalic cisterns may present with CN V symptoms. Intra-axial lesions will often be accompanied by some somatic sensory or motor, vestibular pathway and possibly ocular dysmotility symptoms and related physical findings. Isolated CN V findings are possible from the cisternal segment through and including its rootlets and ganglion within the trigeminal cistern. The cisternal segment will be the site of microvascular compression lesions (Chapter 73) (Figs. 95.1 and 95.2).

Skull Base and Exit Foramina: Paracavernous and Superior Orbital Fissure Syndromes

When all three divisions of the trigeminal nerve are involved, it is likely related to a cavernous sinus–region lesion (Figs. 73.1–73.9, 74.1–74.6, 75.1–75.5, and 95.3). When ocular motility is also involved, the lesion will be either of this segment or in the brain stem or perhaps cisternal. If visual acuity is added, the lesion is almost assuredly at the orbital apex.

Peripheral Course and End Organ/Innervation

The three main divisions of the trigeminal nerve may be a source of specific individual complaints. The maxillary division is by far the one most likely to be the source of complaints and the one where a structural lesion is most likely to be found. These lesions are most often a compressing malignancy or perineural spread of a malignant tumor (Figs. 21.8–21.10, 21.48–21.52, 24.1–24.5, 95.4, and 95.5). Each major division must be followed from its origin in the trigeminal ganglion out its exit pathway and to its distal point of supply (Fig. 95.6). This includes distal branches such as the frontozygomatic nerve, infraorbital nerve, and auriculotemporal nerve. The anatomy of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) layer is helpful in evaluating the most distal course of the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of CN V. This very complex nerve supplies sensory innervation to the face, sinuses, nasal cavity, deep facial spaces, TMJ, and periauricular region, to name a few. It is extraordinarily important to search all of the structures of the craniofacial region supplied by CN V when asked to evaluate a patient with a trigeminal neuropathy.

FIGURE 95.1. T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of a patient with HIV infection presenting with severe left facial pain. The intra-axial lesion causing the trigeminal symptoms was due to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

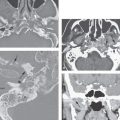

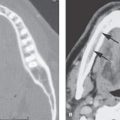

FIGURE 95.2. A patient presenting with typical trigeminal neuralgia. The cause of the left fifth nerve symptoms as seen on this series of computed tomography images was a dural-based mass projecting into the upper prepontine cistern (arrows). It slightly compressed the root entry zone of the trigeminal nerve. It was subsequently proven to be meningioma.

Wasting of the muscles of mastication due to denervation atrophy may be seen as a secondary sign of a mandibular division deficit (Fig. 24.8). The denervation process, which in its natural history includes a phase of contrast enhancement of the denervated muscles, must be recognized as an effect rather than cause of the neurologic deficit.

APPLIED ANATOMY

Cranial Nerve Nucleus and Cisternal Segment

CN V has a very long sensory nucleus centered in the pons with extensions to the lower mesencephalon and upper cervical spinal cord (Fig. 137.1). Its motor nucleus is essentially confined to the pons. The larger sensory and smaller motor divisions exit the anterior and lateral aspect of the mid pons to travel a short distance in the perimesencephalic cisterns. The motor division is more medial than the sensory division. The nerve then passes beneath the petroclival ligament, with its rootlets fanning out in the trigeminal cistern often referred to as the “Meckel cave.” The rootlets then gather anteriorly and inferiorly within the lateral dura of the cavernous sinus forming the trigeminal ganglion.

Foraminal/Skull Base Segment

At the trigeminal ganglion, the trigeminal nerve divides into three segments: the ophthalmic division (V1), the maxillary division (V2), and the mandibular division (V3). V1 exits the superior orbital fissure. V2 exits via the foramen rotundum in the base of the sphenoid bone (Figs. 44.12 and 44.24–44.27 and Chapter 44). V2 send branches to the pterygopalatine fossa and then on to the nasal cavity, sinuses, and face, as discussed subsequently. V3 passes through the foramen ovale into the upper masticator space, remaining there for about 2 cm or so within the mesial aspect masticator space (Fig. 78.27).

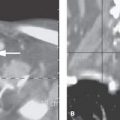

FIGURE 95.3. A patient with progressive facial pain of relatively subacute onset with additional signs and symptoms related to cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. A: Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image showing abnormal enhancement of the cisternal segment of the trigeminal nerve (white arrow) as well as adjacent dural enhancement. Within the trigeminal cistern, the trigeminal nerve can be seen as an area of lesser enhancement (black arrow) surrounded by abnormal enhancing tissue. More anteriorly, the second division of the trigeminal nerve is thickened and enhances (white arrowhead). The normal trigeminal nerve in the cistern is shown on the right for reference (black arrowheads). B: T1W coronal image with contrast showing diffuse infiltration of the cavernous and paracavernous region (arrows) extending into the foramen ovale (arrowhead). C: Contrast-enhanced T1W coronal image showing the normal superior orbital fissure on the right side for reference (white arrowhead). The disease in the paracavernous region clearly involves the orbital apex and superior orbital fissure (white arrow) and the V2 division (black arrowhead). The patient had diminished visual acuity. This process was subsequently proven to be pseudotumor involving the cavernous sinus, also known as Tolosa-Hunt syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree