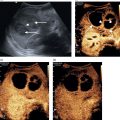

Tom Heller1,2, Michaëla A.M. Huson3, and Francesca Tamarozzi4 1 Lighthouse Clinic, Lilongwe, Malawi 2 International Training and Education Center for Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States 3 Radboud University Medical Center, Department of Internal Medicine and Radboud Center of Infectious Diseases (RCI), Nijmegen, The Netherlands 4 Department of Infectious Tropical Diseases and Microbiology, WHO Collaborating Centre on Strongyloidiasis and other Neglected Tropical Diseases, IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital, Negrar di Valpolicella, Verona, Italy Ultrasound plays a key role in the diagnosis and management of hepatic infections. It is particularly helpful in resource‐limited, mainly tropical, settings where ultrasound is usually the first tool to screen, diagnose, guide treatment, and follow up cases, as it is often the only imaging modality available besides chest X‐ray [1]. Ultrasound is sensitive in the detection of many infections. However, it lacks specificity, particularly in necrotic abscess‐like infections, which can mimic benign (e.g. haemorrhagic cysts) or malignant (e.g. necrotic tumours) conditions. Like any diagnostic test, it is important to interpret it in the context of epidemiological and clinical details such as age, sex, and area of residence, exposure, presenting history, symptoms, and current immune status to achieve an accurate presumptive diagnosis. Often this needs to be narrowed down further by employing laboratory tests, for instance serology, or by using other diagnostic imaging modalities. Aspiration and biopsy are frequently required to conclude the final diagnosis and ultrasound is an ideal modality to guide this process. In this chapter, we will summarise the most important infections of the liver, their sonographic presentations, further tests that may be utilised, and potential treatment options. Infections of the liver will be categorised as parasitic, bacterial, fungal, and viral. Viral hepatitis, although prevalent in many tropical areas and probably the most frequent liver infection worldwide, is not included in this chapter as it is discussed in more detail in Chapter 8. Ultrasound can help with the detection of numerous parasitic diseases endemic in tropical regions. As ultrasound is the imaging mode of choice in echinococcosis and plays a key role in amoebic liver abscess (ALA), these topics will be described in more detail. Schistosomiasis is an important cause of portal hypertension in tropical settings and will also be addressed in detail. Other parasitic infections that can be detected by ultrasound will be described briefly, including Fasciola, Toxocara, Opisthorchis, Clonorchis, and Ascaris. Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is caused by the larval stage of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato. CE has a worldwide distribution, and is especially prevalent in livestock‐raising areas. The natural cycle of the parasite develops between dogs and livestock. In humans, after accidental ingestion of parasite eggs from the environment, CE cysts may develop in any organ or tissue, most commonly in the liver (approximately 80% of cases) followed by the lungs (approximately 20% of cases). CE cysts evolve through stages, either spontaneously or as a consequence of treatment. When symptoms occur, they are due either to the growth of the cyst(s) exerting pressure on neighbouring structures, or to the loss of cyst integrity or its rupture, causing local and/or systemic manifestations. Symptoms are non‐specific and depend on the organ affected. For those in the liver, these include poor appetite, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice. The most common complication is rupture, which can cause jaundice in case of communication with the biliary tree, anaphylactic reaction, or may be further complicated by superinfection or dissemination (secondary echinococcosis). Ultrasound is the examination of choice for the diagnosis and staging of abdominal CE cysts. The currently accepted international classification of CE cysts, based on hepatic ultrasound features, is the World Health Organization Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis (WHO‐) classification [2]. This includes six stages, each characterised by a pathognomonic sign that, when clearly visible, allows the diagnosis of CE (Figure 7.1): Figure 7.1 CE cyst stages and suggested stage‐specific clinical management of cystic echinococcosis (CE). PAIR = puncture, aspiration, injection of a scolicidal agent, and re‐aspiration. Non‐PAIR percutaneous treatments include several percutaneous techniques using cutting instruments and large‐bore catheters to evacuate the entire cyst content. Source: Bélard S et al. (2016), The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. It is important to remember that some calcification in CE cysts can occur at any stage (i.e. presence of calcification alone does not classify a CE cyst as CE5 stage), but these calcifications are always peripheral. CE cysts are also always avascular, therefore the presence of Doppler signal within the cyst excludes the diagnosis of CE. Rule‐in/rule‐out diagnosis in case of suspected CE can be achieved by the following: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performs better than computed tomography (CT) in defining the pathognomonic features of CE cysts; these techniques are mainly required pre‐operatively to define the relation of the cyst with neighbouring structures. Asymptomatic hepatic CE should be managed using a stage‐specific approach: Symptomatic CE should be treated surgically. Some experts also add peri‐operative praziquantel to albendazole in cases of invasive procedures. An alternative, less effective drug than albendazole is mebendazole. During albendazole intake, regular (e.g. monthly) monitoring of blood cell counts and liver enzymes is recommended. Ultrasound follow‐up is indicated yearly for a minimum of five years. AE is caused by the larval stage of the tapeworm Echinococcus multilocularis. Similar to CE, humans acquire infection through accidental ingestion of parasite eggs, but AE infection is much less frequent than CE, it only occurs in the Northern Hemisphere, and its cycle is sylvatic. The natural cycle of the parasite develops between wild canids (especially foxes) and different species of small rodents. AE lesions are infiltrative and metastasising tumour‐like lesions, cholangiocarcinoma being the main differential diagnosis. The primary organ affected is almost invariably the liver. AE lesions grow slowly and the asymptomatic period may last 5–15 years or longer; many infections are diagnosed at a late stage. Jaundice is the most common presenting symptom, often associated with itching, right upper quadrant pain, and fever in case of cholangitis or superinfection of the necrotic centre of the lesion. Loco‐regional extension and distant metastases may cause a variety of symptoms. The WHO‐IWGE classifies AE by PNM staging (P = extent and location of the parasitic lesion; N = invasion of neighbouring organs; M = presence of metastases). According to ultrasound appearance different AE’s sonographic patterns are described [2, 3] (Figure 7.2): In comparison to CE, no pathognomonic imaging signs of AE exist and especially the haemangioma‐ and metastasis‐like patterns may pose a diagnostic challenge. However, the presence of calcifications and the pattern of contrast enhancement may suggest the diagnosis of AE. Figure 7.2 Sonographic patterns of E. multilocularis (a) ‘Hailstorm’, (b) ‘pseudocystic’, (c) ‘ossification’, (d) ‘hemangioma‐like’ and (e) ‘metastais like’ appearance of alveolar echinococcosis lesions. Source: Courtesy of Dr Claudia Wallrauch. Serology is almost invariably positive; however, high cross‐reactivity exists with CE, which makes the differential diagnosis between the two infections at times difficult, especially in co‐endemic areas. Definitive diagnosis may be achieved by biopsy followed by histology or PCR. If untreated, the prognosis of AE is poor. After assessment of the extension of the disease, the options may be curative resection (partial debulking should be avoided) followed by two years of albendazole, or prolonged, often life‐long, albendazole administration, with interventional radiology or endoscopic procedures if complications occur. In some cases, liver transplant followed by albendazole may be an option. Regular follow‐up with serology, imaging, and monitoring of blood cell counts, aminotransferases, and albendazole‐sulfoxide blood levels is required. Discontinuation of albendazole treatment may be possible in case of seronegativity and negative fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography (FDG‐PET; delayed imaging acquisition). Amoebic liver abscess (ALA) is the most common extraintestinal manifestation of Entamoeba histolytica infections and around 8% of patients with intestinal amoebiasis develop hepatic abscesses. In tropical settings they are far more common than bacterial abscesses. After ingestion of the amoebic cysts through contaminated food or water, amoeba trophozoites develop in the bowel and cause amoebic colitis, although the infection is often asymptomatic. In some cases the parasites invade the mucosa and travel via the mesenteric and portal veins to the liver. Here substantial liquefaction necrosis of hepatocytes is induced 5–7 days after arrival of the amoeba in the liver, explaining the abrupt clinical onset with fever, right upper quadrant pain, and leucocytosis in previously healthy individuals. For unknown reasons ALAs are more frequent in adults than in children and more frequent in male than in female patients. ALAs are more frequently seen in the right liver lobe (77%); the most common location is the posterior segment of the right lobe. In the majority of patients a single lesion is found; nevertheless, about 40% of patients have two or more lesions. On ultrasound, typically a hypoechoic lesion measuring about 4–10 cm is seen (Figure 7.3). Inside the lesion there are often fine internal echoes. The shape is round and regular; due to the reduced echogenicity, mild distal acoustic enhancement is seen. The lesion usually lacks significant wall echoes. All of these features may also occur in pyogenic abscesses and are thus not sufficient to make a distinction between the two. Figure 7.3 Round hypoechoic amoebic liver abscess without significant wall in the dorsal segments of the right lobe. Rarely, ALAs can present with atypical patterns like echogenic nodules, thick echogenic walls, mural nodules, and septations, causing difficulties in the differential diagnosis of solid masses and other lesions. Sonographic findings need to be combined with clinical information and serological results to reach the correct diagnosis. Diagnostic aspiration is an option and produces an ‘anchovy sauce’–like product, but it is rarely indicated. Serology for anti‐amoebic antibodies will be positive in more than 90% of patients with ALA and in combination with the history and the ultrasound findings it is usually diagnostic. The treatment of choice is metronidazole. Usually a very rapid clinical response is seen within days – sonographically lesions shrink far more slowly. Initially the lesions tend to lose echogenicity with effective treatment and can become anechoic. For uncomplicated ALA there is no strong evidence for percutaneous aspiration or drainage over medical treatment only. Indications for percutaneous drainage are lack of response to metronidazole therapy, multiple or very large lesions, and continuing diagnostic uncertainty. ALAs may rupture into the pericardium, pleural cavity, or peritoneal cavity if they are located superficially. Prevention of these complications is another reason for initial drainage. Time to complete resolution depends on the initial size of the lesion; it may take up to 3–6 months. In approximately 5% of ALA patients the resolution is not complete and post‐ALA residual lesions may be found. These are usually hypo‐ to isoechoic compared to liver tissue and show a hyperechoic wall. The residual lesions were found to persist for more than a decade and may pose differential diagnostic problems. While genito‐urinary schistosomiasis is caused by infection with the trematode Schistosoma haematobium, all other Schistosoma species affecting humans, mainly S. mansoni and less frequently S. japonicum and other species, cause intestinal and hepato‐splenic schistosomiasis. S. mansoni occurs in Latin America, sub‐Saharan Africa, and the Middle East, while other species have more localised geographical distributions in Africa, the Middle East, or Asia. Humans get infected percutaneously upon contact with freshwater contaminated with the infective larval stage of the parasite (cercariae), released in the water by a snail intermediate host. Mature adult worms live in the mesenteric venules, where females produce eggs that pass through the intestinal wall and are eliminated with faeces. In freshwater, eggs hatch ciliated miracidia that infect a competent snail, perpetuating the cycle. Acute infection with juvenile worms and early production of eggs may be clinically accompanied by a febrile systemic syndrome known as Katayama syndrome, characterised by fever, malaise, urticarial rash, abdominal pain, and respiratory symptoms. Chronic hepato‐splenic disease results from prolonged release of eggs. Many eggs are not excreted and granuloma form around eggs trapped in the intestine and the liver, inducing a chronic inflammation that leads to disease manifestations. In the liver, chronic pathology is characterised by periportal fibrosis, also known as Symmer’s pipe‐stem fibrosis. Periportal fibrosis eventually leads to portal hypertension and collateral circulation, with variceal bleeding being the most dangerous complication of the disease. Clinical manifestations include hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, abdominal discomfort, and, in advanced cases, ascites and hematemesis. Pulmonary hypertension may also occur due to pulmonary arteritis from hematogenous spread of eggs.

7

Tropical Infections of the Liver

Parasitic Infections of the Liver

Cystic Echinococcosis

Introduction and Clinical Picture

Ultrasound Features

Further Investigations

Treatment and Follow‐Up

Alveolar Echinococcosis

Introduction and Clinical Picture

Ultrasound Features

Further Investigations

Treatment and Follow‐Up

Amoebic Liver Abscess

Introduction and Clinical Picture

Ultrasound Features

Further Investigations

Treatment and Follow‐Up

Liver Schistosomiasis

Introduction and Clinical Picture

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree