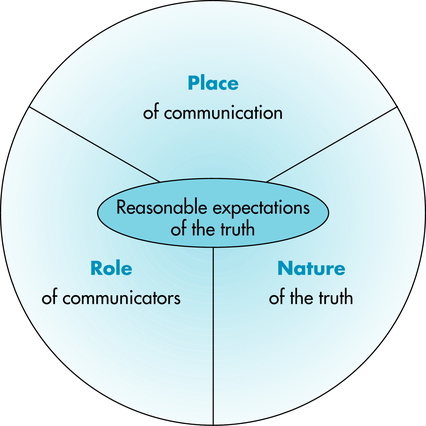

5 After completing the chapter, the reader will be able to perform the following: • Define truthfulness, veracity, and confidentiality. • Identify the three variables involved in expectations of truth. • Cite circumstances in which a person has a right to the truth. • List and define three types of obligatory secrets. • Explain the importance of the professional secret. • Cite exceptions to confidentiality. • Identify and discuss the elements of defamation, including slander and libel per se. • Specify situations that may trigger the duty to warn third parties. • Identify the conflict between confidentiality and disclosure of HIV and AIDS. • List the statutory obligations regarding AIDS and HIV. • Define the patient’s right of access to medical records. • Identify ways that the patient’s right of access may come into conflict with the ethical and legal principles by which the imaging professional must practice. The information required during the informed consent process is discussed in Chapter 4. This chapter discusses issues regarding truthfulness and confidentiality in imaging professionals’ dealings with patients, surrogates, and other health care professionals. For example, if an imaging professional overhears a physician telling a patient not to worry, the chest x-ray film looks fine, but she should have another x-ray film in 6 months, should the imaging professional indicate to the patient that she has a spot on her lung and may have a problem? Truthfulness is summed up in two commands: “Do not lie, and you must communicate with those who have a right to the truth.”1 The first command leaves the imaging professional free to not communicate to avoid telling a lie, and the second constrains the professional to share information only with those who have a right to the truth. A lie is a falsehood told to a person who has a reasonable expectation of the truth.1 The ethics of lying is judged in terms of consequences for the individual and society. The expectation of truth varies with the following conditions: All three of these conditions are related to the obligation of confidentiality and the right to privacy (Figure 5-1). Considerations of confidentiality are as important as truthfulness in the discussion of patients’ rights and the imaging professional’s obligations. Confidentiality concerns the keeping of secrets: “A secret is knowledge a person has a right or obligation to conceal. Obligatory secrets are secrets that arise from the fact that harm will follow if a particular knowledge is revealed.…These are the natural secret, the promised secret, and the professional secret”1 (Box 5-1). The AHA’s Committee on Biomedical Ethics notes the following conditions in which confidentiality may be breached2: Exceptions to confidentiality may be debated in discussions of the family’s need to know (as in the case at the beginning of this chapter), exceptions concerning children and adolescents (e.g., abortive processes, treatment for sexually transmitted diseases), medical condition of public figures (e.g., whether Americans have the right to know if the President is in critical condition), use of hospital records for research and billing purposes, and third-party payers (e.g., need for payment balanced against patient confidentiality). Exceptions to confidentiality are discussed further in the legal section of this chapter and are listed in Box 5-2.

Truthfulness and Confidentiality

ETHICAL ISSUES

TRUTHFULNESS AND VERACITY

Definitions

Circumstances for Expectations of the Truth

CONFIDENTIALITY

EXCEPTIONS TO CONFIDENTIALITY

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine