TUMORS OF THE SUBMANDIBULAR GLAND AND SPACE AND TUMORLIKE CONDITIONS

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can help to determine whether a submandibular space mass is intrinsic or extrinsic to the submandibular gland and its most likely etiology.

- If a primary submandibular neoplasm is identified, imaging will help to establish its local extent, including its relationship to the mandibular division of the facial nerve, mylohyoid muscle, and mandible.

- Imaging can evaluate cervical metastasis in patients with a submandibular gland cancer.

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance findings significantly facilitate medical decision making in submandibular gland tumors.

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance may be used for surveillance imaging following treatment for submandibular gland tumors.

INTRODUCTION

A Dilemma: Submandibular Region Mass of Glandular or Nonglandular Origin

Mass lesions in the submandibular region may be intrinsic or extrinsic to the submandibular gland (SMG). If nonglandular, such neoplastic masses will be due to level 1A adenopathy; tumors arising from the floor of the mouth, mandible, and masticator space; or rarely, primarily in the submandibular space (SMS) (Fig. 182.1). A unique and common example is the plunging or diving ranula. Developmental masses were discussed in Chapter 180.

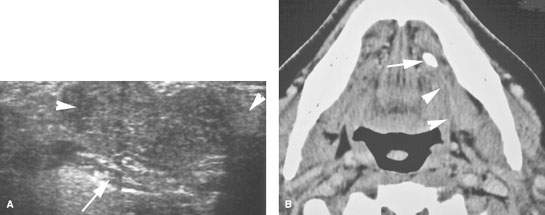

Infiltrating systemic disease such as sarcoidosis, as well as manifestations of autoimmune sialoadenitis (Chapter 181) and rarely lymphoma, can mimic an SMG epithelial-origin tumor if those conditions are not otherwise known to be present (Fig. 182.2A,B). The same is true of manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Bilaterality in these conditions is an important clue to the systemic etiology of the disease (Fig. 182.2C,D). Diagnostic imaging has a major impact on sorting out these possibilities and thereby significantly altering medical decision making in a high percentage of patients. The contributions are equally important in some cases of intrinsic glandular epithelial-origin neoplasms (Table 182.2).

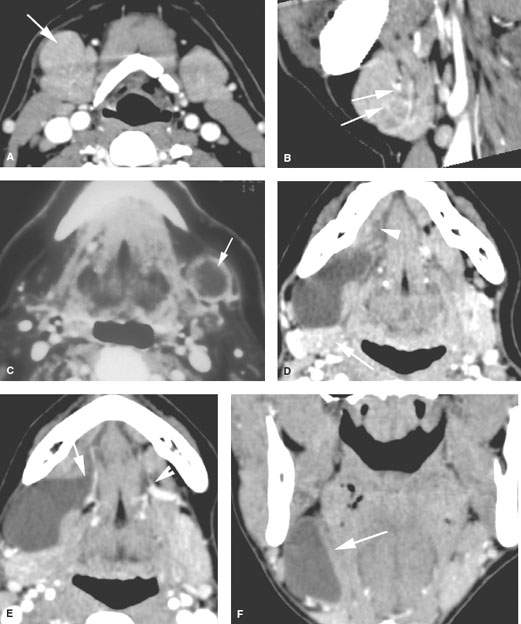

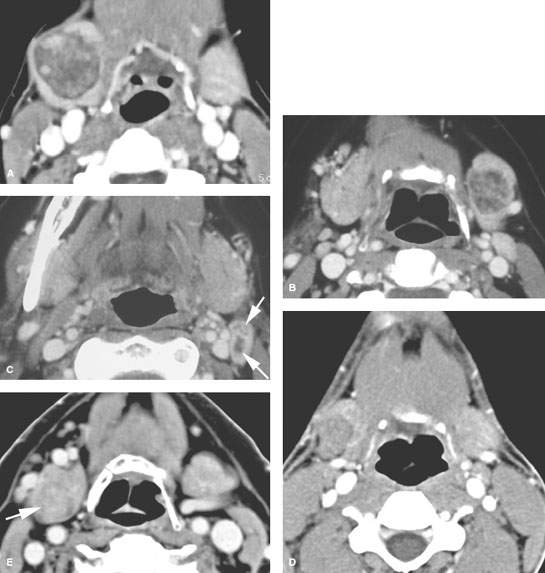

FIGURE 182.1. Eleven patients with abnormality extrinsic to the submandibular gland (SMG) presenting as masses of the submandibular space (SMS) and potentially of the SMG. All patients had contrast-enhanced computed tomography studies, except one in which a conventional sialogram was done. A, B: Patient 1. The mass, which on several images appeared to be possibly contiguous with the SMG, was shown to be extrinsic to the gland. This was most convincingly demonstrated on multiplanar images, which showed the facial vessels as seen in (B) (arrows) to be compressed between the reactive lymph node and the SMG. C: Patient 2 presented with a submandibular metastatic lymph node. The patient had not recalled having any skin cancer removed earlier in life. This node represented failure of that skin cancer in regional level 1 nodes. D–H: Patient 3. The image in (D) demonstrates a fluid density mass occupying the SMS mainly posterior to the floor of the mouth and displacing the SMG (arrow) posteriorly. There is a component of the fluid density within the sublingual space (arrowhead) that appears to be continuous with the main cystic collection over the back edge of the mylohyoid muscle. In (E), the axial section shows an additional area of possible connection with the floor of the mouth through an anatomic gap in the mylohyoid muscle (arrow) as it is in its more normal state on the opposite side transmitting a somewhat enlarged vein (arrowhead). In (F), the mass is mainly within the SMS, lying lateral to the mylohyoid and hyoglossus muscles (arrow). In (G), the ranula follows the neurovascular bundle through the mylohyoid muscle gap on the right (arrow) compared to its normal anatomic status on the left. In (H), the fluid clearly occupies the sublingual space as its site of origin (arrow) compared to the normal sublingual space on the right side. I: Patient 4, also with a ranula presenting as an SMS mass (arrow) with a small component in the floor of the mouth. The plunging ranula likely enters the SMS through the gap in the mylohyoid muscle anteriorly and inferiorly (arrowhead). (NOTE: These two cases of ranula show that the sublingual space and the fluid collection produced by a ranula may plunge into the SMS via either a gap in the mylohyoid muscle anteriorly or over the back edge of the mylohyoid muscle or both.) J: Patient 5 presenting with a SMS mass shown to be due to a lipoma composed of mature fat lying predominately laterally in the SMS. K: Patient 6 presenting with a left submandibular region mass that felt very firm, and there was concern about a primary SMG neoplasm. The study showed the mass to be due to a lipoma containing mature fat displacing the gland and compressing it somewhat, likely contributing to the clinical finding of a firm mass in that region. L: Patient 7 presenting with an SMS mass that was slightly tender. The mass was shown to be mainly fatty but containing other tissue. This was removed and turned out to be a lipoma with some elements of cellular degeneration but no evidence of liposarcoma. M: Patient 8 presenting with bilateral submandibular-region masses seen to be due to excessive accumulations of both encapsulated and unencapsulated fat. This mimicked bilateral SMG pathology and therefore had systemic pathology. This was shown to be due to lipomatosis and related lipomas. N: Patient 9. Before the advent of CT, conventional sialography was used to determine whether submandibular-region masses were intrinsic or extrinsic. This sialogram from the early 1980s shows an intrinsic mass (arrows) displacing the ducts within the SMG. Such studies are no longer done for this purpose. O: Patient 10 presenting with a rock hard mass in the angle of the mandible and submandibular region proven by CT to be due to a calcified lymph node. P, Q: Patient 11 presenting with a pulsatile mass in the SMS on this study shown to be due to a high-flow vascular malformation.

Submandibular Tumors

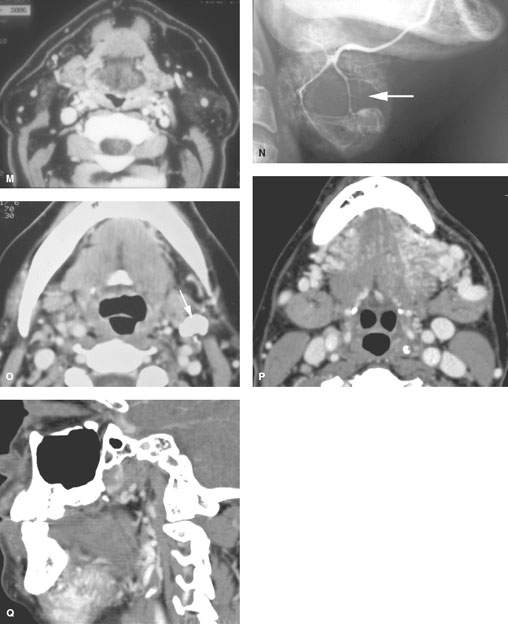

Major salivary glands contain several different groups of functioning and support cells. This leads to the variety of possible histologic diagnoses discussed in Chapter 22. Precise histologic diagnosis by frozen section and needle biopsy may be difficult, especially with regard to distinguishing between benign and malignant neoplasms. Those planning care must be very aware of this limitation. Imaging features can sometimes help to anticipate malignancies. The main problem is that benign-appearing masses may be malignant, and malignant-appearing masses are sometimes histologically benign. Because of this dilemma, both benign and malignant tumors are discussed in this chapter along with some of their more common potential mimics. However, predicting in advance whether a mass is benign or malignant most often does not alter the initial, usually surgical, approach to care (Fig. 182.3).

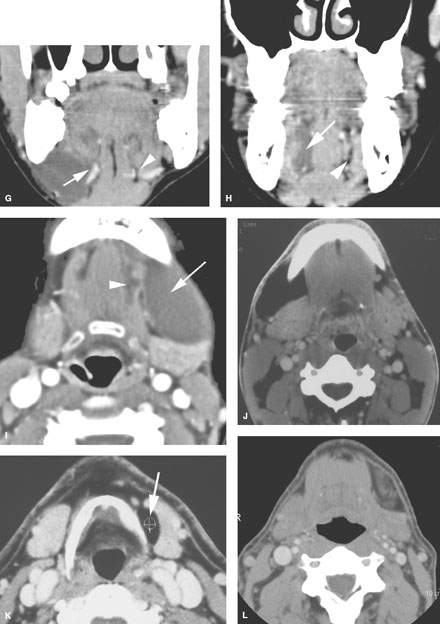

FIGURE 182.2. Two patients with potential manifestations of lymphoma. A, B: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) in Patient 1 presenting with a left submandibular region mass shown to be due to primary submandibular gland lymphoma. This was the only site of the patient’s disease and a highly unusual circumstance. C, D: Patient 2. Contrast-enhanced CT study done to evaluate palpable bilateral submandibular masses. These were due to lymphoepithelial cysts as seen in (D); the parotid glands were also involved. This was the initial presentation of this patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Embryology

The development of the SMG is such that tumors may arise within contiguous accessory tissue that extends far anteriorly in the SMS, where it may then be contiguous with sublingual salivary tissue in the floor of the mouth via anatomic defects in the anterior aspect of the mylohyoid muscle. Similar contiguity of the SMG with the sublingual gland may occur over the back edge of the mylohyoid.

Applied Anatomy

The important anatomic relationships of the SMG that impact medical decision making in benign and malignant tumors of the gland and SMS are reviewed in Chapter 175 and summarized here. This anatomy includes the following:

- Its relationships to the structures that bound the SMS, including the mandible, mylohyoid muscle, and superficial fascia or platysma and the lower parapharyngeal and masticator spaces

- Course of the mandibular branch of the facial nerve and the lingual branch of V3

- Level 1 lymph nodes and their drainage patterns (Chapters 149 and 157)

FIGURE 182.3. Three patients illustrating that benign and malignant disease within the submandibular gland (SMG) may have a relatively nonaggressive morphologic appearance. The studies also illustrate how tumors may be difficult to see within the SMG. A: Patient 1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) shows a well-circumscribed, surgically proven benign mixed tumor. B, C: Patient 2. There is a well-circumscribed mass in the left SMG demonstrated in (B). In (C), a metastatic lymph node containing multiple metastases (arrows) indicates that this was a malignant lesion eventually proven to be an intermediate-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma. D: Contrast-enhanced CT study in Patient 3 with a palpable right submandibular region mass. This well-circumscribed mass was shown to be a low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma. E: Patient 4 presented with a right submandibular region mass. Contrast-enhanced CT shows the mass to be intrinsic to the gland but not much different from normal glandular parenchyma. The image was optimized for contrast and level settings to demonstrate the lesion as it is seen. This was proven to be a benign mixed tumor at surgery.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

Specific computed tomography (CT) protocols for various indications appear in Appendix A and are discussed in more detail in Chapter 175. CT data sets should be obtained with about 1-mm collimation reconstructed at 1- to 3-mm slice thickness depending on the clinical situation. Such acquisitions will be suitable for adequate multiplanar reformations. If sections are too thin, there may be an important loss in low-contrast resolution that may cause a lesion to “hide” within the tissue density of the normal glands. Such occasionally poor contrast between a salivary gland mass and the normal gland can be daunting, and in any questionable case, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be done to more confidently exclude a mass if one is strongly suspected clinically (Fig. 182.3E). This issue actually makes MRI a better first choice for the evaluation of a parotid-region mass if there is no inflammatory component to the clinical presentation.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Specific magnetic resonance (MR) protocols for various indications appear in Appendix B. MRI should be done with 3- to 4-mm sections and a field of view of 12 to 16 cm. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) may be used since such imaging may contribute information about the likely benign or malignant nature of the mass. However, it is unlikely that any serious clinical decision will be based on such data relative to that from the clinical setting, anatomic imaging, and biopsy.

Since it is not predictable when contrast might be useful, a study of the SMG and sublingual gland regions is generally done with acquisitions before and after contrast injection. Contrast-enhanced MR studies are clearly useful when there are associated neuropathies that must be evaluated, if the lesion is aggressive, and/or if the cervical nodes are to be evaluated.

Ultrasound

Standard scanning techniques as described in Chapter 4 are used.

Radionuclide Studies

Radionuclide studies include those using technetium, iodine, and fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG), with such studies done for other purposes frequently showing activity in normal glands (Fig. 5.9).

Conventional Sialography

Conventional sialography is no longer used to evaluate submandibular-region masses (Fig. 182.1N). It can be used to evaluate the ductal system in usually chronic inflammatory conditions, especially when main duct changes are an issue (Chapter 181). Sialography should be avoided in acutely inflamed glands, especially if a pyogenic infection is likely.

Pros and Cons

General Approach

Magnetic Resonance and Computed Tomography

MR and CT are the most used imaging studies to evaluate an SMS mass. Such expensive studies may not be necessary if the mass is discrete and freely mobile. If there is a hint of an inflammatory condition of salivary gland or other origin clinically in the presence of a mass, then CT is preferred over MR.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound (US) may be used to determine whether superficial lesions are intrinsic or extrinsic to the SMG and to follow such masses if they are likely reactive nodes (Figs. 4.1 and 182.4) or if their benign nature is established by further imaging, biopsy, and/or definitive surgery is not elected. US may be used to guide percutaneous biopsies of the SMG that cannot be done by palpation alone and may help to improve the diagnostic yield of those procedures by ensuring that the sampling is from the mass and not surrounding normal gland. The combination of US and biopsy can be a very quick and cost-effective way to evaluate an SMS mass that is likely to be benign or related to an enlarged level 1A lymph node.

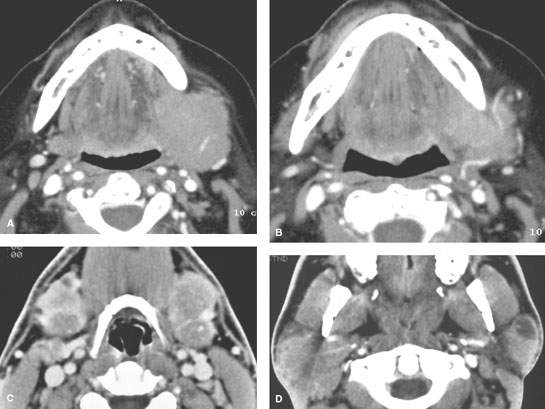

FIGURE 182.4. A patient presenting with minimal tenderness in a mass in the left submandibular region. A: Ultrasound shows a lobulated mass within the submandibular gland (arrowheads) lying external to the mylohyoid muscle (arrow). Despite the lack of inflammatory findings, the CT with contrast in (B) shows the changes in the gland not to be due to a mass lesion but secondary to a stone impacted in the submandibular duct (arrow), with associated periductal inflammatory changes (arrowheads).

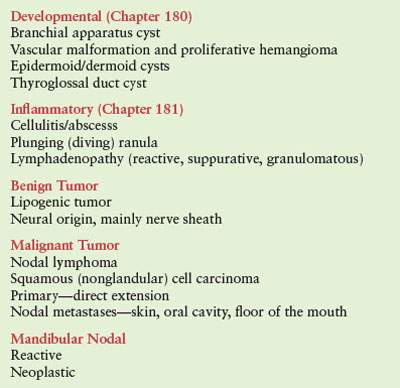

TABLE 182.1. SUBMANDIBULAR SPACE MASSES OF NONGLANDULAR ORIGIN

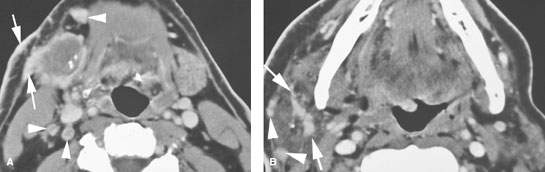

FIGURE 182.5. A patient presenting with tenderness and swelling in the right submandibular region. Both the pain and tenderness were progressive, and the mass was enlarging. A: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography study showing an aggressive mass replacing the submandibular gland with growth out of the capsule of the gland to invade the superficial musculoaponeurotic system along the expected course of the marginal mandibular division of the facial nerve (arrows) as well as thickening of the overlying skin and subcutaneous soft tissues. In addition, multiple lymph nodes are present that enhance abnormally (arrowheads). Some of these measure ,5 mm and contain obvious metastatic deposits (arrowheads). B: Gross spread along the mandibular division of the facial nerve is present within the parotid gland (arrows) as well as metastatic parotid lymph nodes (arrowheads). The metastatic nature of the nodes is mainly based on the avid enhancement as opposed to any focal nodal changes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree