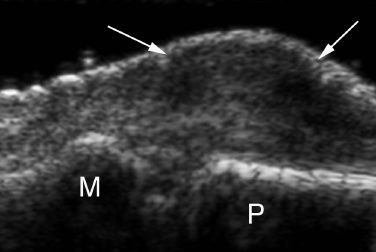

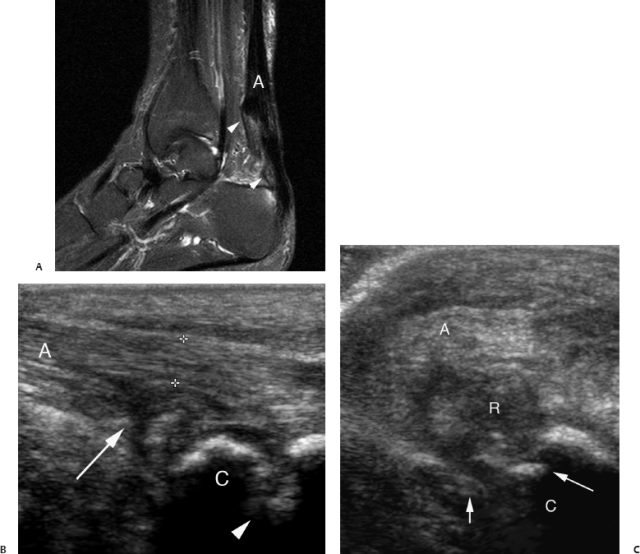

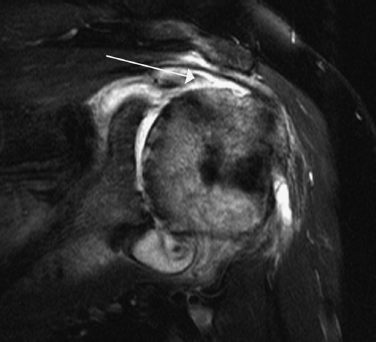

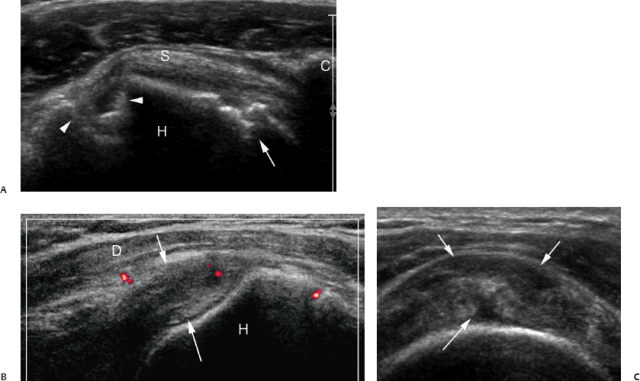

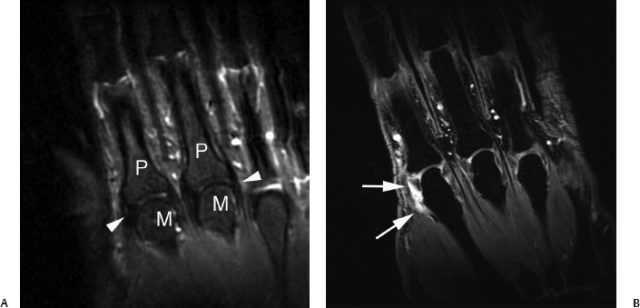

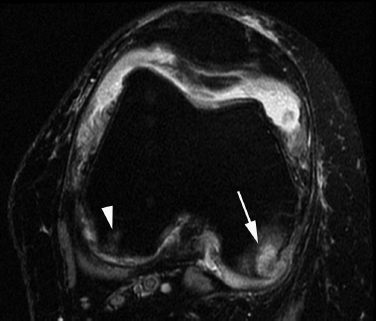

11 Ultrasound for Rheumatoid Arthritis Robert R. Lopez-Ben Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a severe multisystem autoimmune disease with an overall prevalence of ~1% worldwide—thus affecting tens of millions of people, with approximately a 3:1 female-to-male incidence ratio. The course of the disease is unpredictable and highly variable from patient to patient, but chronic joint inflammation can lead to fixed joint deformities. This can lead to significant disabilities and loss of function or ability to care for oneself. It has now been shown that early treatment with antiinflammatory and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS) will decrease the extent of joint damage and in some cases achieve a remission of the disease. By intervening early in the disease course, functional outcomes in these patients will improve. Some of the newer therapeutic agents used in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis like tumor-necrosis factor α inhibitors, and other agents targeting different components of the inflammatory response like rituximab and abatacept, can be very effective. However, they are expensive and can be associated with significant side effects. Establishing the diagnosis accurately early in the disease course, as well as assessing disease activity frequently, is of critical clinical significance. The classic clinical presentation of bilaterally symmetrical polyarticular pain and swelling in a rheumatoid-type distribution in the hands and feet, along with the presence of morning stiffness, usually suggests the diagnosis of RA in most cases. The presence of serologic markers of chronic inflammation like rheumatoid factor, and typical radiographic findings including joint space narrowing and marginal erosions, will then usually establish the diagnosis in clinical practice. Radiographs of the hands and feet have been the traditional imaging method to assess disease diagnosis and progression in RA patients. However, determining active synovial inflammation on physical exam may be difficult, especially in obese patients, patients with an asymmetrical involved joints distribution, or patients with long-standing diseases who may have fibrotic pannus. Serologic markers of inflammation are nonspecific. More specific radiographic markers of active synovial inflammation like marginal bone erosions may not be detected early in the disease course, with up to 70% of patients reported to have normal radiographs at clinical presentation. Because radiography cannot directly visualize the synovium and cartilage, radiographic assessment of synovitis depends on secondary findings like joint space narrowing and periarticular osteopenia. These have significant interobserver variability. Bone erosions are only diagnosed with confidence when the radiographic beam has profiled them in tangent. Identifying these early RA patients from patients with a self-limiting undifferentiated arthritis clinical syndrome or other conditions like seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and even noninflammatory conditions like fibromyalgia or knucklepads, can be at times difficult for the clinician and lead to diagnostic uncertainty (Fig. 11.1). Cross-sectional imaging techniques like computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound have traditionally been used in this patient population to evaluate for complications of chronic inflammation of RA like tendon tears, entrapment neuropathies, or secondary joint infections (Figs. 11.2, 11.3, 11.4). Based on more aggressive treatment planning in early disease and the high false-negative rate of radiographs in early RA, cross-sectional imaging is now used to directly evaluate the synovium, as well as assess the bone, marrow, and cartilage for evidence of inflammation and joint damage. Cross-sectional imaging is more sensitive to bone erosion detection when compared with radiographs. MRI and ultrasound have been shown to be more sensitive than clinical exam in determining extent of synovitis and erosions. They can be utilized earlier in the disease course to determine, as well as to follow, more objective parameters of joint in-flammation like effusions, synovial proliferation, and small marginal erosions that can be radiographically occult. These techniques can better gauge the severity of the inflamma-tion and monitor objective parameters to possible response to therapeutic agents. Fig. 11.1 Knucklepads. This patient presented with periarticular soft tissue swelling and presumed rheumatoid arthritis. Longitudinal ultrasound image of the dorsal soft tissue fullness shows a subcutaneous hypoechoic soft tissue mass (arrows) with a normal underlying proximal interphalangeal joint. P, distal aspect of the proximal phalanx; MP, base middle phalanx ring finger. Fig. 11.2 Achilles tendon tears in patients with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis (RA). (A) Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the ankle shows a partial thickness tear of the anterior fibers of the distal Achilles tendon (A) (arrowheads denote tear extent). Note the focal high signal in the marrow of the calcaneus at the insertion of the tendon. These focal areas of subcortical marrow edema can progress to frank marginal erosions. (B) Longitudinal ultrasound image of a different patient. There is disruption of the anterior fibers of the Achilles tendon by a partial tear (arrow). Calipers bracket the intact posterior fibers. There is an erosion (arrowhead) at the calcaneal (C) insertion site of the tendon. (C) Transverse ultrasound image of the same patient at the level of the Achilles insertion. The posterior intact Achilles fibers (A) remain hyperechoic. There is disruption of the Achilles anteriorly and distension of the retrocalcaneal bursa (R), adjacent to the calcaneal (C) erosion (arrows). MRI has been touted as the new gold standard in RA clinical trials for assessment of synovial and tenosynovial inflammation (Fig. 11.5). When compared with ultrasound, MRI is unique in that it can depict early marrow “edema”—a marker for abnormal overlying cartilage and possible future erosion development (Fig. 11.6). MRI may also quantitate overall synovial volumes and rate of enhancement better, which may be a quantitative measure to assess drug response. However, in clinical practice, utilizing MRI for the assessment of disease activity in RA patients has definite shortcomings. It remains relatively expensive and not as readily accessible to patients in most rheumatology clinics when compared with radiography and even ultrasound. To maximize detail of intraarticular anatomy in small joints, a limited field of view with high spatial resolution is often necessary. This limited field of view can make overall assessment of multiple joints time consuming. Small erosions in very small joints like the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints can be difficult to resolve from underlying edema or due to partial volume averaging. Fig. 11.3 Rotator cuff tears in the setting of long-standing rheumatoid arthritis. Coronal T2-weighted fat-suppressed magnetic resonance image of the left shoulder. There is a high-grade, partially retracted and delaminating tear of the articular surface of the distal supraspinatus tendon (arrow). There is marked joint effusion and synovitis as well as pancartilage loss in the glenohumeral joint. Ultrasound is a safe, portable, more readily available, and less-expensive alternative imaging modality to evaluate syd-novitis and joint erosions in multiple joints with immediate diagnostic information. Ultrasound is also effective for interventional guidance for joint and tendon sheath aspirations or injections. The limitations of ultrasound include the dependence on operator technique, and the limited so-nographic window for visualization of certain portions of joints with complex bony anatomy like the wrist. Although scanning protocols and techniques can be variable and not standardized among different practitioners, there is increasing validation for the use of ultrasound in the early diagnosis and monitoring of therapy response in RA patients. Given the typical involvement of the hands and feet early in the disease course, we routinely evaluate with ultrasound the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and PIP joints of the hands, the wrists, and the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints of the feet in these patients. Fig. 11.4 Rheumatoid arthritis patient complaining of shoulder pain. (A) Transverse ultrasound image of the right shoulder at the level of the bicipital groove (arrowheads). The subscapularis tendon (S) shows normal echogenicity. Its course can be seen from the coracoid (C) to its lesser tuberosity insertion at the humeral head (H). A marginal erosion is seen (arrow) in the anterior humeral head and erosive changes of the bicipital groove (arrowheads) are present as well as a partial tear of the long head of the biceps tendon at this location. (B) Longitudinal ultrasound image at the level of the greater tuberosity of the humerus (H) anteriorly. There is marked hypoechogenicity and loss of the normal fibrillar structure of the distal supraspinatus tendon (arrows), with increased power Doppler signal in the distal tendon tear. The overlying deltoid muscle (D) is noted. (C) Transverse ultrasound image at the level of the greater tuberosity anteriorly. There is marked swelling and hypoechogenicity extending from articular to bursal surface consistent with a complete tear of the distal supraspinatus tendon (arrows). Fig. 11.5 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) assessment of metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints. Coronal T1-weighted fat suppressed gradient recall MRIs after contrast enhancement with gadolinium contrast. (A) Normal appearance of the metacarpal head (M) and proximal phalanx (P) of the index and long finger marrow and cartilage. The collateral ligaments and tightly apposed joint capsule are denoted by the arrowheads. (B) Patient with early rheumatoid arthritis on a new therapeutic agent. Arrowsshow nodular synovial enhancement and thickening of the index finger MCP joint. The exam is centered on the MCP joints, and the proximal interphalangeal joints are included in the field of view, but the wrists are not completely included. Fig. 11.6 Axial T2-weighted fat suppressed magnetic resonance image of the knee in a patient with known rheumatoid arthritis. There is marked joint effusion and synovitis. Arrowhead denotes focal area of subchondral marrow edema in the posterior medial femoral condyle at an area of overlying cartilage loss. Arrow shows marginal erosion and surrounding marrow edema in the lateral condyle posteriorly.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree