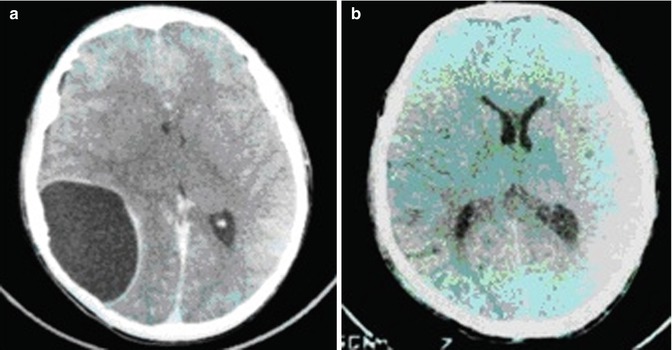

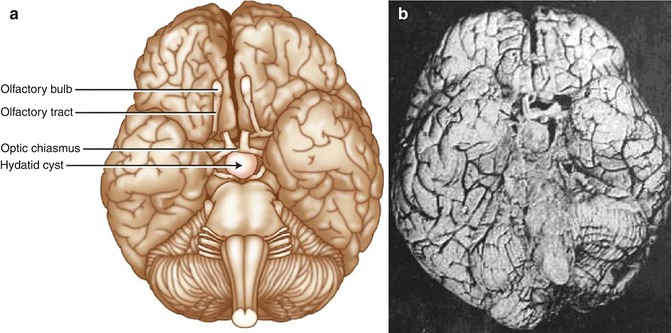

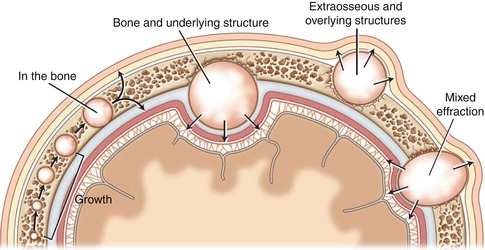

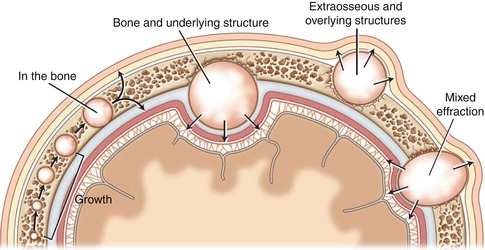

Fig. 21.1

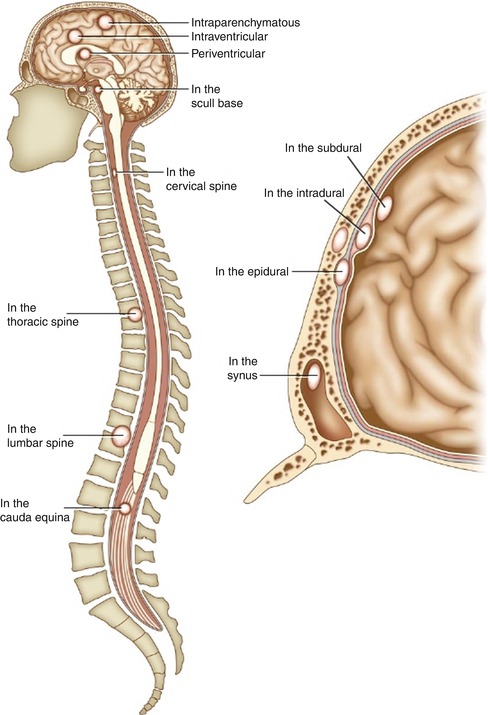

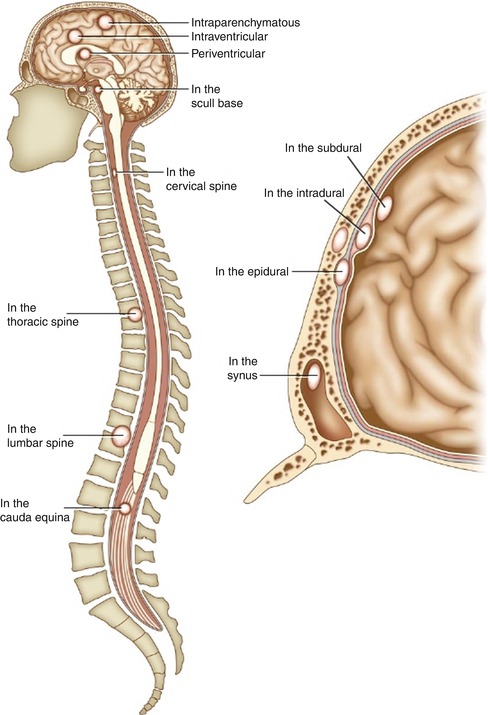

The vascular dissemination of hydatidosis

Calvarium

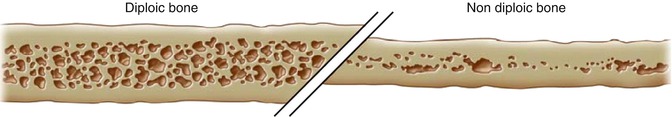

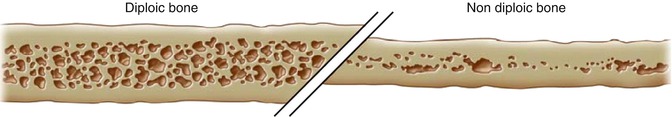

Hydatid disease in the calvarium is usually the rarest in the CNS. Anatomically, the bones of the calvarium, which has a protective function toward the brain, are made of one layer of spongious bony tissue flanked on the outside and on the inside by two other layers of compact laminar bone tissue such is the case of diploic bones (Figs. 21.2 and 21.3).

Fig. 21.2

Diploic vs. nondiploic sagittal bone section

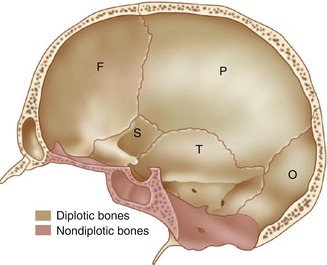

Fig. 21.3

Sagittal cut-through section of the skull showing the distribution of the diploic and nondiploic bones. F Frontal bone, P parietal bone, T temporal bone, S sphenoid bone, O occipital bone

The bones of the base of the skull are nondiploic and the core spongious bony tissue may be very little represented or absent. While bones of the calvarium are more prone to destruction by hydatid cysts, the bones of the skull base can also be involved, although this situation is much rarer (Fig. 21.4). The first one to describe bone destruction as a consequence of hydatid cysts in the skull was Monro in 1811 (Arseni et al. 1981). There were other scarce presentations in the literature of hydatid disease in the diploe (in 1872 by Verdale, in 1901 by Herrera and Cranwell, in 1909 by Goyanes). Felix Deve himself managed in 1949 to gather 637 cases of hydatid disease in the skeleton, of which 22 cases were positioned at the level of the calvarium (quoted from Arseni et al. 1981). Another peculiar manifestation of hydatidosis is in the petrous part of the temporal bone. Three such cases were presented in the literature by Schroeder et al. 1953 (quoted from Arseni et al. 1981).

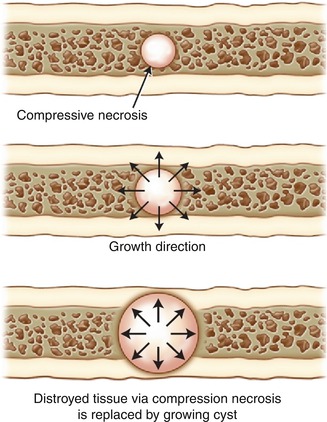

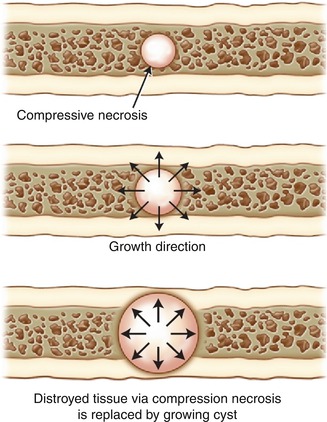

Fig. 21.4

Hydatid cyst growing in the diploe. The inner and outer tables are gradually spread apart by the eccentrical growth of the cyst

The pathogenic mechanism of hydatid disease in the calvarium is quite difficult to explain. Arseni and Samitca mention in 1957 in their monograph regarding hydatidosis a single case of hydatid disease in the cranial vault. As to the bones of the skull base, researchers such as Arana Iniguez showed that 7.6 % out of 145 cases of cerebral hydatid disease attacked the bony structures, especially the petrous portion of the temporal bone (quoted from Arseni et al. 1981). Recently, a case in which an E. granulosus cyst produced a brain abscess in a 28-year-old patient has been reported (Llanes et al. 2008). In this case, the evacuation of the brain abscess was performed with a combined otolaryngologic and neurosurgical procedure (canal wall down mastoidectomy and temporal craniotomy) (Llanes et al. 2008). Another rarity we found in skull vault-related unusual presentations of hydatidosis is the presence of the disease in the viscerocranium – especially the sinuses. The maxillary sinus (Goldsher et al. 1983) and maxillary antrum (Copley et al. 1992) are two of the rarest locations for hydatidosis in the skull even in the endemic areas across the world.

The surgical approach for hydatid cysts in the skull vault doesn’t present too many surgical difficulties. Many authors recommend an oval incision in the skin, in the form of a horseshoe to provide an intact removal of the hydatid cyst penetrating the calvarium. In endemic areas, the diagnosis must be clearly made, absolutely without biopsy and without compromising the integrity of the cyst in the subjacent structures including the bone and meninges. In non-endemic areas, a case of multifocal hydatidosis, metastasized or polycystic, has to be correctly diagnosed. In this respect, all the investigative data has to be correlated so that the diagnosis and surgical approach are not carried out inappropriately (Fig. 21.5). One case stands out. It is the case of a 14-year-old boy which after birth started showing a particular progressive deformity of the calvarium. Despite what looked like hydrocephalus or scaphocephalus, the child showed satisfactory results in school. The child started suffering from latero-cervical pain which irradiated to the back of the head and associated with nausea and lately with intermittent vomiting. The radiograph showed a characteristic cyst-like formation 12 cm in length and 5 cm thick. Once opened, the calvarium contained more than 80 microcysts ranging from 3 mm to 5 cm. At the periphery of the cyst, the calvarium measured 1.5 cm in thickness. The depressed inner sheath of the bone was also removed (thus complete craniectomy was achieved) with a minimal blood loss and well-tolerated surgery. A few hours after surgery, shock installed; however, the patient managed to withstand due to glucose serum and blood perfusions. Twelve hours postoperative the patient started showing right-sided hemiplegia with cerebral edema. Gradually the patient recovered and left the hospital with a minimal deficit which was completely resolved 4 months after surgery (Fig. 21.6).

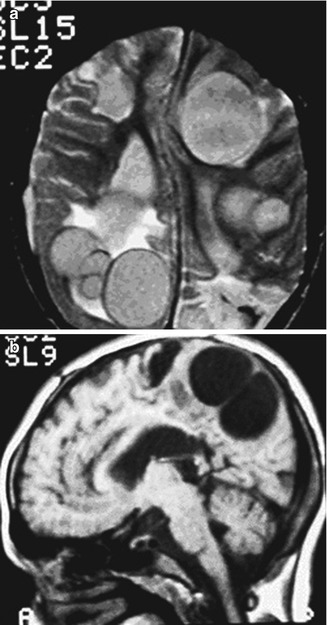

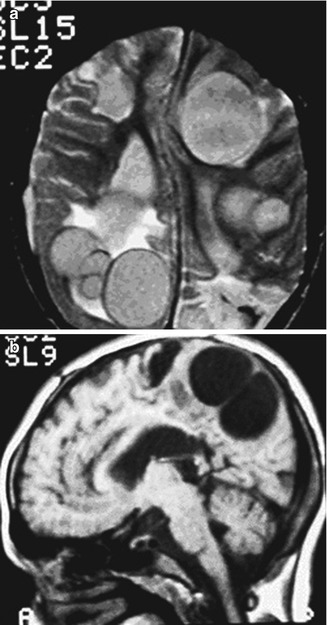

Fig. 21.5

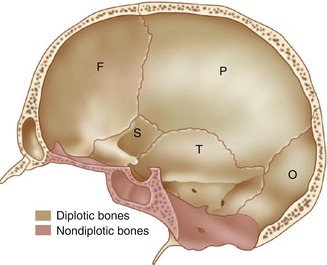

Axial (a) and sagittal (b) MRIs of multiple hydatid cysts in the brain

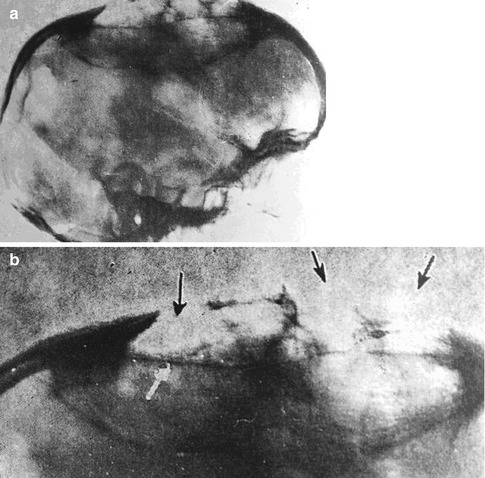

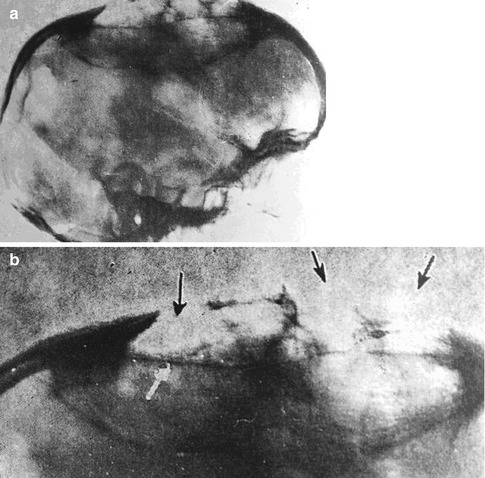

Fig. 21.6

(a) Lateral radiograph showing the cyst. Note the length and the width of the displacement of the inner and outer sheath of the calvarium. (b) Radiograph centered on the cyst. Arrows represent areas where the hydatid cyst has destroyed the outer sheath of the calvarium

The hydatidosis of the skull is discussed in Chap. 5 in detail.

Craniocerebral Extradural

Extradural hydatid disease occurs at the moment when one or more E. granulosus oncospheres end up via the bloodstream in the epidural space of the cerebrospinal axis; this includes the skull and spine. The space we are referring to consists of the space enclosed between the outer surface of the dura mater and the internal surface of the skull which continues through the foramen magnum downward with the internal surface of the spinal canal, lined by the tectorial membrane, posterior longitudinal ligament, and yellow ligament and is filled with the peridural adipose tissue (Figs. 21.7, 21.8, and 21.9).

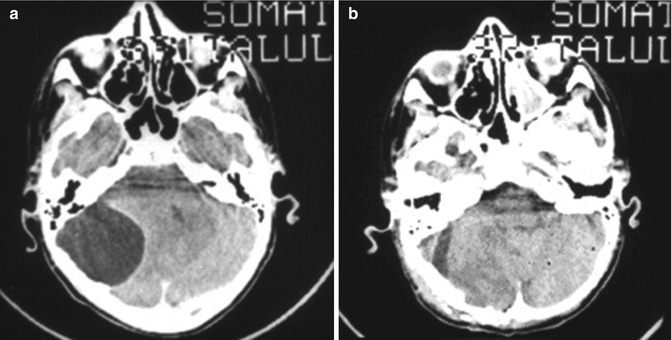

Fig. 21.7

Preoperative (a) and postoperative (b) aspects of an extradural hydatid cyst in the posterior fossa

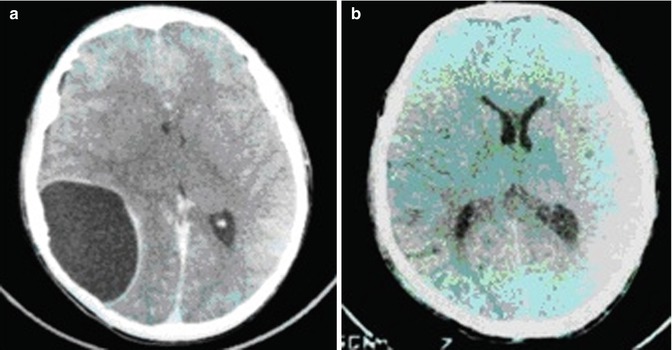

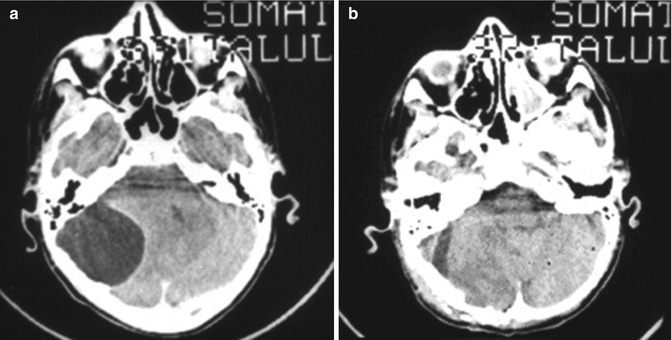

Fig. 21.8

Preoperative (a) and postoperative (b) aspects of an extradural hydatid cyst in the parietooccipital region of the brain

Fig. 21.9

Distribution of the dura mater and the development of various hydatid cysts

After the larva has penetrated the inner bone layer, it will grow outside of the dura mater, developing into a substantial cyst of viscous consistency. The cyst will then compress the brain matter leading to the characteristic symptoms. The clinical features of this manifestation are dominated by the slow evolution of the cyst which is translated into a raised intracranial pressure syndrome and diminished visual acuity. Patients usually end up at the hospital when the cyst has exaggerated dimensions (Arseni et al. 1981). Sporadic manifestations of extradural hydatidosis in the literature have also been found more recently (Sharma et al. 2010). The extradural meningeal space is generally affected during a multifocal hydatid disease (Siddiqui et al. 2010).

Interesting enough is the fact that more and more unusual manifestations of extradural hydatid disease appear in the literature. We mention only for historical purpose six cases (Arseni et al. 1981).

We describe two such cases: one is mentioned in the literature in 1949 (Arseni et al. 1981). Here, the patient, a young child, had a large destruction of bony substance associated with an enormous cyst 425 cm3 in volume that contained nine daughter cysts which varied in size. The child died 4 days after surgery as a result of violent epileptic seizures triggered by 100,000 units of penicillin administered at the site of the cyst. The second case was published in 1959 (Arseni et al. 1981). The patient showed a left frontal pulsatile tumefaction. The cyst had drilled through the walls of the left frontal sinus, and the secondary sinusitis masked the presence of the cyst. Three such cases are presented by Arseni et al. (1981) as part of their personal list of cases.

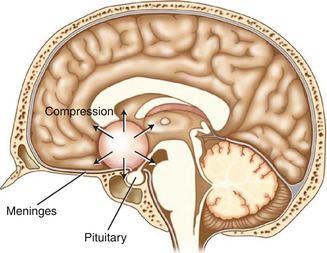

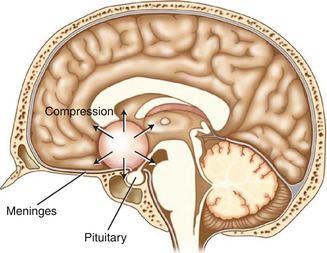

Craniocerebral Extradural Sellar

An extremely interesting case was signaled in the Maghreb where a young Bedouin woman became fertile again 13 years after a hydatid cyst that was pushing against her pituitary stalk was removed. The removal of the cyst returned full hormonal functions (Mazor et al. 1986) (Fig. 21.10).

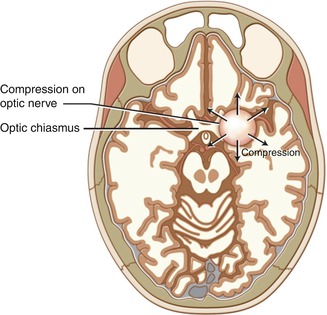

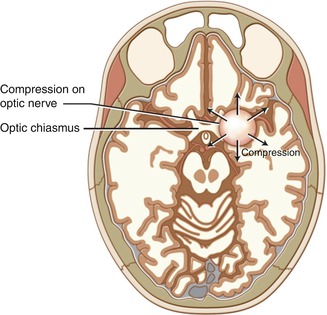

Fig. 21.10

Example of hydatid cyst compressing against the pituitary stalk

We are familiar with one other case of such nature, taken from the literature, in which a 38-year-old woman manifesting hypothalamic stupor and absolute mutism presented a hydatid cyst in the area between the diencephalon and pituitary gland. The patient unfortunately died and the cyst was found at autopsy, lying behind the optic chiasmus and in front of the pons. The cyst was herniating between the hemispheres and was the size of a pigeon egg (Arseni et al. 1981). The cyst developed in the tissue of the pituitary gland, the ceiling of which got atrophic and resorbed through a slow process of compression which was doubled by a flattening of the neural portion as well as the whole infundibulo-tuberian area. One such case was also depicted by Arseni et al. (1981) as part of their personal experience in Fig. 21.11.

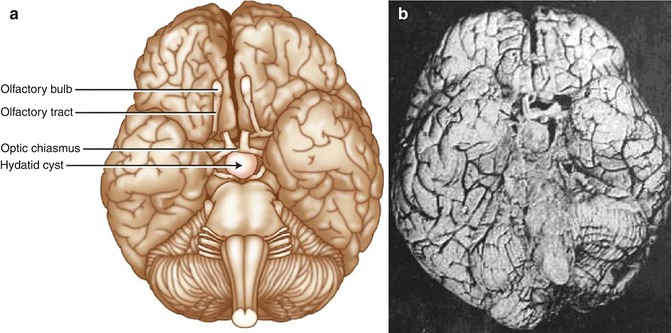

Fig. 21.11

(a) Pathology finding of a hydatid cyst behind the optic chiasmus and in front of the pons. Courtesy of the C. Arseni pathology museum. (b) Pathology finding of a hydatid cyst behind the optic chiasmus and in front of the pons (Courtesy of the C. Arseni pathology museum)

Craniocerebral Extradural Parasellar

Another case of multiple hydatid cysts was spotted in a patient from an endemic area, a 21-year-old man presenting with multiple cranial nerve palsy, impaired eyesight, raised intracranial pressure, and a computed tomography (CT) image showing a hypodense mass with septations and a hyperdense rim. The case pointed out the presence of a parasellar hydatid cyst (Behari et al. 1997).

The recommended surgical approach in such situations is the pterional basal one or the fronto-temporo-orbito-zygomatic one, which can be extended to the needs of the surgeon. The approach is executed in such a way that it will allow the widest exposure of the cyst to permit a complete intact cyst removal. Under no circumstance should the integrity of the cyst be disrupted (Fig. 21.12).

Fig. 21.12

An artistic illustration showing a hydatid cyst in the right parasellar area

Craniocerebral Intradural and Subdural

Unlike neurocisticercosis, literature data shows extremely few cases of intradural manifestations of hydatidosis. Not even data from endemic areas is significant. We describe the case of a 6-year-old child, in which an E. granulosus cyst developed between the dura mater and the arachnoid membrane. The cyst had destroyed the frontoparietal skull as it had grown in all directions unhindered (Arseni et al. 1981) (Fig. 21.13).

Fig. 21.13

Possibilities of evolution for a hydatid cyst

One other interesting case we found is that of a hydatid cyst which laid both extradurally and subdurally. The larva which traveled via the middle meningeal artery positioned itself in the dura mater. Given the particularities of the dural blood network, the parasite most likely stopped in the deepest layer, which is very similar to the lymphatic capillaries. From here on, the parasite starts to grow and develop more or less as in the case we invoked, in the tissue underneath the dura mater, separated from the cortex by the leptomeninges (Arseni et al. 1981). It is most likely that after the larva perforated the dura mater, it was able to grow both subdurally and epidurally. We feel forced to mention that usually hydatid cysts remain attached to the inner surface of the dura mater.

The surgical approach in such situations is conducted via a wide skin incision that will encircle the whole surface of the cyst. The craniotomy/craniectomy should resect a surface of the skull wider than the cyst. These rare situations cannot be handled through a minimally invasive approach as the purpose of the procedure is to expose the cyst and the adjacent and subjacent structures. The removal of the cyst will be made via the intact enucleation of Arana Iniguez. It consists of delivering the cyst by introduction of a flexible catheter between the cyst and the receiving cavity while injecting hypertonic fluid (Kalangu et al. 2011). A general rule for the removal of the cysts: preserve the integrity of the cyst at all costs.

Intraencephalic

All the literature data mention the prevalence of hydatidosis in the cerebral hemispheres. Most of the cases of intracerebral hydatidosis are present in the left hemisphere. These cysts can reach tremendous dimensions and volumes, for example, 770 g, as described by Bahloul et al. (2009) (Figs. 21.14 and 21.15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree