Etiology

Renal calculi are typically caused by crystallization of supersaturated stone-forming materials in the urine. Calcium, in the form of calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, and calcium urate, is the most common stone-forming material. Uric acid is the second most common component. Other less common components include xanthine, cystine, struvite, and precipitation of medications such as the protease inhibitor indinavir sulfate in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Alternatively, renal pathologic processes may initiate crystal formations within the renal tubules that are extruded into the renal collecting system to undergo further growth. Urinary stasis secondary to chronic obstruction or reflux, urinary pH abnormalities, and chronic infections also may contribute to stone formation.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Nephrolithiasis and ureterolithiasis represent a significant cause of urinary obstruction and abdominal pain. Infections, such as pyelonephritis, pyonephrosis, or renal abscess, may complicate stone disease and may be difficult to differentiate clinically. Imaging evaluation is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of stone disease and detect complications.

The lifetime risk for forming renal stones differs in various parts of the world: it is 1% to 5% in Asia, 5% to 9% in Europe, and 13% in North America. The composition of stones and their location in the urinary tract, bladder, or kidneys also may significantly differ in different countries. Renal stone disease is slightly more common in males than in females and in whites than in blacks. Stones in the upper urinary tract are related to lifestyle and are more frequent among affluent people, those living in developed countries, and in those with diets high in animal protein. A high frequency of stone formation occurs among hypertensive patients and among those with a high body mass index.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Nephrolithiasis and ureterolithiasis represent a significant cause of urinary obstruction and abdominal pain. Infections, such as pyelonephritis, pyonephrosis, or renal abscess, may complicate stone disease and may be difficult to differentiate clinically. Imaging evaluation is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of stone disease and detect complications.

The lifetime risk for forming renal stones differs in various parts of the world: it is 1% to 5% in Asia, 5% to 9% in Europe, and 13% in North America. The composition of stones and their location in the urinary tract, bladder, or kidneys also may significantly differ in different countries. Renal stone disease is slightly more common in males than in females and in whites than in blacks. Stones in the upper urinary tract are related to lifestyle and are more frequent among affluent people, those living in developed countries, and in those with diets high in animal protein. A high frequency of stone formation occurs among hypertensive patients and among those with a high body mass index.

Pathophysiology

Most patients with symptomatic renal or ureteral stones present because of flank pain caused by acute ureteral obstruction. The most common location of the stone is in one of the three areas of narrowing in the ureter: the ureteropelvic junction, the pelvic brim as the ureter crosses into the pelvis, and the ureterovesical junction.

Imaging

Radiography

On abdominal radiographs, nephrolithiasis may be identified as focal calcific densities projecting over the renal shadows. Also, ureteral and bladder calculi may be identified on plain radiographs. In patients with a known history of renal calculi who have undergone lithotripsy, plain radiographs may be used to evaluate for residual renal or ureteral calculi. When multiple ureteral calculi are identified after lithotripsy, this is termed steinstrasse, the translation of this German term being “stone street.”

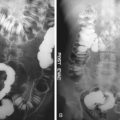

Although computed tomography (CT) has replaced the intravenous pyelogram (IVP) in the majority of patients, some institutions still perform IVP. In acute ureteral obstruction, the IVP demonstrates delayed transit of contrast medium through the affected kidney, with delayed images showing the dilated collecting system and the site of the obstructing stone. The main disadvantage of IVP, in addition to requiring iodinated contrast material, is the potential delay in diagnosis from having to wait for the delayed radiographs.

Computed Tomography

CT is the preferred imaging technique for renal stone detection in many institutes because of its high sensitivity, specificity, and ability to detect radiolucent stones. Typically, renal stone CT protocols are performed without the use of oral or intravenous contrast media, which may obscure the underlying stones. CT has a high diagnostic accuracy in the detection of renal and ureteral calculi and may be used to differentiate among stones of various chemical composition. Recently, ultra–low-dose CT with a radiation dose equivalent to a kidney-ureter-bladder radiograph has been shown to be sufficiently diagnostically accurate in evaluating renal and ureteral calculi. The most common forms of renal stones are all readily identified by routine CT techniques ( Figures 14-1 and 14-2 ). However, urinary stones formed by crystallized protease inhibitors used for HIV therapy are more difficult to identify on CT ( Figure 14-3 ).

Secondary CT signs of acute ureteral obstruction include enlargement of the kidney, which often demonstrates diffusely decreased attenuation secondary to edema, perinephric stranding, and dilatation of the ureter and collecting system (see Figures 14-1 and 14-2 ). Stones are most commonly evident in the three areas of ureteral narrowing: the ureteropelvic junction, the pelvic brim, and the ureterovesical junction. Ureteral stones may demonstrate a “soft tissue rim” sign surrounding the calculus ( Figure 14-4 ), distinguishing a ureteral calculus from adjacent pelvic vein phleboliths. Large intrarenal stones occupying most of the renal pelvis and some of the calyces, known as staghorn calculi, also can be seen on CT ( Figure 14-5 ). CT may show renal parenchymal calcifications in cases of nephrocalcinosis ( Figure 14-6 ).