Vital Signs and Oxygen Administration

OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, the student will be able to:

1. Define vital signs and explain when assessment should be done.

2. List the rates of temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure that are considered to be within normal limits for a child and an adult, male and female.

3. Identify sites and methods available for measuring body temperature.

4. Identify the most common types of oxygen administration equipment and explain any potential hazards.

5. Describe the equipment that must be available and functional in all radiographic imaging departments to monitor blood pressure and to administer oxygen.

6. List the precautions that must be taken when oxygen is being administered.

7. Accurately monitor pulse rate, respiration, and blood pressure.

KEY TERMS

Bradycardia: A slow heart rate of less than 60 beats per minute

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): Disease of the lungs in which inspiratory and expiratory lung capacity is diminished

Cyanosis: A condition in which the blood does not supply enough oxygen to the body, causing a bluish tone to the lips and fingertips

Diastolic: The blood pressure reading that occurs during the relaxation of the ventricles (the lowest number of the reading)

Dyspnea: Difficult breathing resulting from insufficient airflow to the lungs

Hypercapnia: Carbon dioxide being retained in the arterial blood

Hypothalamus: The ventral and medial region of the diencephalon of the brain

Hypoxemia: Low levels of oxygen in the blood

Korotkoff sounds: Extraneous sounds heard during the taking of a blood pressure and may be a tapping, knocking, or swishing sound

Sphygmomanometer: A blood pressure cuff

Systolic: The blood pressure reading taken during the contraction of the ventricles while the blood is in the arteries (the highest number of the reading)

Tachycardia: A fast heart rate of more than 100 beats per minute

Tympanic: Bell-like; resonance pertaining to tympanum

Vital signs: Assessment of the patient’s blood pressure, temperature, pulse, and respiration

Volatile: Easily vaporized or evaporated; unstable or explosive in nature

Many imaging departments in large facilities employ radiology nurses and do not rely on radiologic technologists to perform routine monitoring of equipment and patient vital signs. However, there are still those facilities that do not have the luxury of nursing staff to do these routine assessments of the patient or to operate ancillary equipment. All technologists and student technologists must have the knowledge and understanding of how to monitor and record vital signs. Recording vital sign information in the hospital chart or on the radiology requisition is an important part of the care of the patient.

Technologists must have the basic understanding of how to operate the oxygen cannulas and tanks and what the levels should be for the different types of conditions the patient might have. Because oxygen is a potentially toxic and volatile substance, the radiographer needs to understand the precautions that are to be taken when assisting with oxygen administration or when using radiographic equipment while oxygen is in use.

A physician’s order is not required for vital signs to be measured. Unless a registered nurse is present to do so, vital signs should be taken by the radiographer when a patient is brought into the diagnostic imaging department for any invasive diagnostic procedure or treatment, before and after the patient receives medication, any time the patient’s general condition suddenly changes, or if the patient reports nonspecific symptoms of physical distress, such as simply not feeling well or feeling “different.”

MEASURING VITAL SIGNS

Taking a patient’s vital signs (also called cardinal signs) is an important part of a physical assessment and includes measurement of body temperature, pulse, and respiration. Blood pressure is not a true vital sign category, but is often measured with the other three in the overall assessment of the patient. In the event an emergency situation arises, the technologist must be prepared by knowing how to measure each of the vital signs and know what those readings mean. It is also important to learn what the patient’s vital signs are under normal circumstances because everyone has some variation from what is considered normal for their particular age group. After the baseline vital signs for a patient have been established, it will be easy to determine whether the patient’s current vital signs are deviating from that of the baseline. A patient’s baseline vital signs cannot be established with one reading of pulse, respiration, or blood pressure because of the many variables that can make one reading unreliable. Vital signs must be measured if the patient comes to the diagnostic imaging department for an extensive procedure or examination without a chart, and no registered nurse is available. Changes in vital signs can be an indication of a problem or a potential problem. As a part of the assessment of vital signs, the technologist should be aware of the patient as a whole; the color and temperature of the skin (cool or clammy), the level of consciousness and anxiety, and the patients’ ability to communicate how they are feeling will provide additional information prior to a procedure.

It is the responsibility of the radiographer to make certain that there is a functioning sphygmomanometer, a stethoscope, and the equipment necessary to administer oxygen in each diagnostic imaging room at the beginning of each shift. Emergencies requiring these items arise, and that is not the time to look for this equipment.

Body Temperature

Body temperature is the physiologic balance between heat produced in body tissues and heat lost to the environment. It must remain stable if the body’s cellular and enzymatic activities are to function efficiently. Changes in the body’s physiology occur when the body temperature fluctuates even 2° to 3° C. Body temperature is controlled by a small structure in the basal region of the diencephalon of the brain called the hypothalamus, sometimes referred to as the body’s thermostat.

Chemical processes that result from metabolic activity produce body heat. When the body’s metabolism increases, more heat is produced. When it decreases, less heat is produced. Both normal and abnormal conditions in the body can produce changes in body temperature. The environment, time of day, age, weight, hormone levels, emotions, physical exercise, digestion of food, disease, and injury are some factors that influence body temperature. The body’s cellular functions and cardiopulmonary demands change in proportion to temperature variations outside normal limits.

A patient whose body temperature is elevated above normal limits is said to have a fever, or pyrexia. Fever indicates a disturbance in the heat-regulating centers of the body, usually as a result of a disease process. As body temperature increases, the body’s demand for oxygen increases. Symptoms of a fever are increased pulse and respiratory rate, general discomfort or aching, flushed dry skin that feels hot to the touch, chills (occasionally), and loss of appetite. Fevers that are allowed to remain very high for a prolonged period can cause irreparable damage to the central nervous system (CNS).

The normal body temperature remains almost constant; however, a variation of 0.5° to 1° C above or below the average is within normal limits. The normal body temperature of infants and children up to 13 years of age varies somewhat from these readings. Average body temperatures for each group of individuals are found in Display 6-1.

A person with a body temperature below normal limits is said to have hypothermia, which may be indicative of a pathologic process. Hypothermia may also be

induced medically to reduce a patient’s need for oxygen. It is rare for a person to survive with a body temperature between 105.8° F (41° C) and 111.2° F (44° C) or below 93.2° F (34° C).

induced medically to reduce a patient’s need for oxygen. It is rare for a person to survive with a body temperature between 105.8° F (41° C) and 111.2° F (44° C) or below 93.2° F (34° C).

DISPLAY 6-1 Normal Vital Sign Ranges for Groups of Individuals

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Measuring Body Temperature

The site selected for measuring body temperature must be chosen with care depending on the patient’s age, state of mind, and ability to cooperate in the procedure. Because the reading will vary depending on where it is measured, be sure to specify the site used when reporting the reading. Temperature readings are reported in most health care facilities as follows:

An oral temperature of 98.6° F is written 98.6 O.

A tympanic temperature of 97.6° F is written 97.6 T.

An axillary temperature of 97.6° F is written 97.6 Ax.

A rectal temperature of 99.6° F is written 99.6 R.

Whatever method of measuring body temperature is chosen, the radiographer must assemble the necessary equipment and abide by medically aseptic technique (such as washing the hands and wearing gloves if there is a possibility of coming in contact with blood or other body fluids).

Oral Temperature There are four areas of the body in which temperature is usually measured: the oral site, the tympanic site, the rectal site, and the axillary site. This temperature is taken by mouth under the tongue. The average temperature reading is 98.6° (37° C). An electronic thermometer consists of a probe that is placed under the patient’s tongue and held in place until the instrument signals that it has registered a temperature. If the temperature seems unusually high or low, ask the patient whether they have just had anything hot or cold to eat or drink. The temperature of the mouth may change the temperature registered on the thermometer.

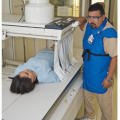

Tympanic Temperature The tympanic membrane thermometer (also called an aural thermometer) is a small, handheld device that measures the temperature of the blood vessels in the tympanic membrane of the ear (Fig. 6-1). This provides a reading close to the core body temperature, if correctly placed. The patient may be sitting upright or may be in a supine position. In the clinical setting, this is a fast and easy method to obtain an accurate temperature reading of the patient in the diagnostic imagining department.

Axillary Temperature The use of the axillary site is the safest method of measuring body temperature because it is noninvasive. It is particularly useful when measuring an infant’s temperature. Unfortunately, the time and precision of placement needed to obtain an accurate reading make this method somewhat unreliable.

When it is necessary to measure temperature using the axillary site, an electronic or a disposable thermometer may be used. The average axillary temperature is 97.6° to 98° F (36.4° to 36.7° C).

PROCEDURE

Taking a Tympanic Temperature

1. Place a clean sheath or cone on the probe that is to be inserted into the external auditory canal.2. Place the probe into the external auditory canal and hold it firmly in place (Fig. 6-2) until the temperature registers automatically on the meter held in the nondominant hand.

3. Remove the probe and read the indicator.

4. Remove the probe’s cover and dispose of it correctly. Remove any gloves and wash hands.

5. Record the reading. Immediately report any abnormal temperature to the radiologist in charge of the procedure.

Rectal Temperature Rectal temperature is taken at the anal opening to the rectum. The average rectal temperature is 99.6° F (37.5° C). The rectal site is considered to provide the most reliable measurement of body temperature because factors that can alter the results are minimized. It is also in close proximity to the pelvic viscera or “core” temperature of the body. Body temperature should not be measured rectally if the patient is restless or has rectal pathology, such as tumors or hemorrhoids. Normally, a rectal temperature is only taken on infant patients and not on adults.

To take a rectal temperature, use a thermometer with a blunt tip. Never use an oral thermometer to take a rectal temperature. Probe covers are often colored red for rectal temperature.

Other Instruments Used to Measure Body Temperature Temperature-sensitive patches are available that can be placed on the abdomen or the forehead of infants or children to measure temperature. If an abnormal temperature is indicated, a more accurate method can be used to verify the actual temperature of the patient.

Another method of obtaining a temperature is done by “scanning” the forehead and the back of the ear with a probe. These thermometers may not be found in a radiology department because they are expensive. However, they are a quick and reliable method for obtaining a baseline temperature.

If a patient’s behavior is unreliable, an unbreakable, disposable, single-use thermometer can be used. Wear gloves as in previous descriptions. The thermometer is removed from its wrapper, and the indicator end is

placed under the patient’s tongue for 1 minute. The beads change color, indicating the patient’s temperature. After recording the temperature, discard the thermometer. The accuracy of these instruments is uncertain but will provide the radiographer with an estimate of what a temperature might be in an unstable situation.

placed under the patient’s tongue for 1 minute. The beads change color, indicating the patient’s temperature. After recording the temperature, discard the thermometer. The accuracy of these instruments is uncertain but will provide the radiographer with an estimate of what a temperature might be in an unstable situation.

PROCEDURE

Taking an Axillary Temperature

1. Obtain the instrument to be used.

2. After putting on clean gloves, dry the patient’s armpit with a paper towel or dry washcloth.

3. Place the thermometer into the center of the armpit.

4. Place the patient’s arm down tightly over the thermometer with the arm crossed over the chest. Gently Taking an Axillary Temperature hold the arm of a child or a restless adult in place until the thermometer has registered, usually about 1 minute.

5. Remove the thermometer and read the temperature.

6. Record the reading and dispose of the thermometer as appropriate.

Pulse

As the heart beats, blood is pumped in a pulsating manner into the arteries. This results in a throb, or pulsation, of the artery. At areas of the body in which arteries are superficial, the pulse can be felt by gently pushing the artery lying beneath the skin against a solid surface, such as bone. The pulse can be detected most easily in the following areas of the body:

Apical pulse: over the apex of the heart (heard with a stethoscope) (Fig. 6-3A).

Radial pulse: over the radial artery at the wrists at the base of the thumb (Fig. 6-3B).

Carotid pulse: over the carotid artery at the front of the neck (Fig. 6-3C).

Femoral pulse: over the femoral artery in the groin (Fig. 6-3D).

Popliteal pulse: at the posterior surface of the knee (Fig. 6-3E).

Temporal pulse: over the temporal artery in front of the ear (Fig. 6-3F).

Dorsalis pedis pulse (pedal): at the top of the feet in line with the groove between the extensor tendons of the great and the second toe (may be congenitally absent) (Fig. 6-3G).

Posterior tibial pulse: on the inner side of the ankles (Fig. 6-3H).

Brachial pulse: in the groove between the biceps and the triceps muscles above the elbow at the antecubital fossa (Fig. 6-3I).

The pulse rate is usually the same as the heart rate. The pulse rate is rapid if the blood pressure is low and slower if the blood pressure is high. The patient who is losing blood has an unusually rapid pulse rate and a very low blood pressure. This occurs because the body knows that it is not getting enough blood to the body organs. Therefore, the heart will pump harder to get more blood out to the body. The normal average pulse rate in an adult man or woman in a resting state is between 60 and 90 beats per minute. The normal average pulse rate for an infant is 120 beats per minute. A child from 4 to 10 years of age has a normal average pulse rate of 90 to 100 beats per minute. For the normal values for each group of patients, refer Display 6-1.

Assessment of the Pulse

The pulse rate is a rapid and relatively efficient means of assessing cardiovascular function. Tachycardia is an abnormally rapid heart rate (over 100 beats per minute), and bradycardia is an abnormally slow heart rate (below 60 beats per minute). If a registered nurse is not present to take the pulse rate, be prepared to make this assessment before beginning any invasive diagnostic imaging procedure in order to establish a baseline reading and to reassess it frequently until the procedure is complete and the patient leaves the department. The radial pulse is usually the most accessible and can be taken most conveniently on an adult patient. It should be counted for one full minute. If there is any irregularity of the radial pulse rate, take the apical pulse. The apical pulse is also monitored if the patient’s radial pulse is inaccessible.

For infants and children, the apical pulse is the most accurate for cardiovascular assessment. The femoral, popliteal, and pedal pulses are assessed bilaterally if peripheral blood flow is to be assessed.

When assessing pulse rate, report the strength and regularity of the beat as well as the number of beats per minute.

The normal rhythm of the pulse beat is regular, with equal time intervals between beats. The pressure of the fingers should not obliterate the pulse. When even the slightest pressure of the fingers causes this to happen, report the pulse as weak or thready. If the beat is irregular, unusually rapid, unusually slow, or unusually weak, immediately report this to the physician in charge of the patient. Changes in pulse rate during a procedure must also be reported.

The normal rhythm of the pulse beat is regular, with equal time intervals between beats. The pressure of the fingers should not obliterate the pulse. When even the slightest pressure of the fingers causes this to happen, report the pulse as weak or thready. If the beat is irregular, unusually rapid, unusually slow, or unusually weak, immediately report this to the physician in charge of the patient. Changes in pulse rate during a procedure must also be reported.

FIGURE 6-3 (A) Apical pulse. (B) Radial pulse. (C) Carotid pulse. (D) Femoral pulse. (E) Popliteal pulse. |

FIGURE 6-3 (Continued) (F) Temporal pulse. (G) Dorsalis pedis pulse (pedal). (H) Posterior tibial pulse. (I) Brachial pulse. |

Equipment needed to assess the pulse includes a watch with a second hand and a pad and pencil to record the findings. For monitoring the apical pulse, a stethoscope that has been cleaned will be needed.

The pedal, popliteal, and femoral pulses are often monitored during special diagnostic imaging procedures to ascertain that the patient’s circulatory status in the lower extremities is satisfactory. When this is done, the pulses are not always counted. Instead, they are palpated and assessed as present and strong, weak, regular, or irregular. Mark the areas on the body with a marking pen where the pedal and popliteal pulses are palpated so that they may be rechecked as necessary.

When recording pulse rate, use the abbreviation P for pulse and AP for apical pulse. For example, P 80 equals a pulse rate of 80 beats per minute. Record any abnormalities and immediately report these to the patient’s physician.

Respiration

The function of the respiratory system is to exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide between the external environment and the blood circulating in the body. Oxygen is taken into the lungs during inspiration. It passes through the bronchi, into the bronchioles, and then into the alveoli, which are the gas-exchange units of the lungs. Oxygen is transported to the body tissues by the arterial blood. Deoxygenated blood is returned to the right side of the heart through the venous system. It is then pumped into the right and left pulmonary arteries and reoxygenated by passing through the capillary network on the alveolar surfaces. The blood is then returned to the left side of the heart through the pulmonary veins for recirculation. During this process, carbon dioxide is also deposited in the alveoli and exhaled from the lungs during expiration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree