Vomiting is common in infancy. Parents reporting that their infant is vomiting may be dealing with regurgitation from nonpathological “spitting up” after feeds, which can be normal in newborns and usually resolves over time. Clinicians fear vomiting secondary to obstruction, which can be a life-threatening emergency. Imaging evaluation aids the clinician, in conjunction with the history and physical examination, in distinguishing between these causes. The choice of diagnostic study depends on the suspected etiology of the symptoms, and the appropriate study is performed to diagnose or exclude these potential causes. As discussed throughout this textbook, a systematic approach optimizes imaging evaluation. In the case of the vomiting infant, we always need to ask the age of the infant and if the vomiting is bilious or nonbilious. Only with the answers to these two key questions can the appropriate study be selected. Time of onset of symptoms is also helpful in study selection. Because missing a correctable problem can lead to catastrophic consequences, the most dangerous possible etiologies must be excluded first.

Once the study has been chosen, it must be performed appropriately. We will review optimal techniques for radiographic, fluoroscopic, and ultrasound (US) examinations.

Bilious Vomiting

Bilious Vomiting Within the First 2 Days After Birth

Midgut malrotation with volvulus causes vascular compromise of the midgut and, if not promptly surgically corrected, may cause bowel necrosis and death. This is the most dreaded cause of bilious vomiting in infants and, therefore, is the entity that must be first excluded. Bilious vomiting from obstruction of the duodenum by Ladd bands in the setting of midgut malrotation without volvulus may also cause bilious emesis, as can other causes of proximal and distal shiftenterobstruction. Approximately 20% of newborns with bilious emesis have a surgical etiology, typically malrotation, Hirschsprung disease, or atresias. About 10% have a nonsurgical distal obstruction, such as functional immaturity of the colon. However, nearly two-thirds of newborns presenting with bilious vomiting have no obvious cause; this has been called idiopathic bilious vomiting and may be secondary to reflux or gastric dysmotility, both commonly seen in otherwise healthy infants.

Is the Obstruction Proximal or Distal?

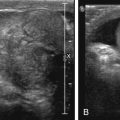

A radiograph to distinguish between proximal and distal causes of obstruction should be the first study obtained. If the radiograph is normal or nonspecific, malrotation must be excluded. An upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) is usually performed for this purpose. Some prefer an initial attempt at sonographic evaluation of the duodenum and superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and vein (SMV) to assess for midgut malrotation with or without volvulus. If volvulus is detected, surgery can be expedited without need for UGI. If malrotation without volvulus is detected or suspected, urgent confirmatory UGI may be deferred, depending on local surgical preference. If normal location of the duodenal–jejunal junction (DJJ) cannot be demonstrated on UGI series, the patient should be taken for immediate surgical exploration. In addition to midgut malrotation, causes of proximal obstruction that may be discovered at surgery include duodenal stenosis or web, annular pancreas, and preduodenal portal vein.

Midgut Malrotation

During fetal development, the midgut distal to the duodenum herniates into the umbilical coelom and rotates 270 degrees before reentering the abdomen. Subsequent fixation of the various mesenteries to the abdominal wall places the third portion of the duodenum in the retroperitoneum and positions the DJJ in the left upper quadrant and the cecum in the right lower quadrant, with a broad intervening mesentery along which the small bowel runs. Failure of this process can occur at different stages, leading to nonrotation or malrotation of the midgut, without a retroperitoneal duodenum. Depending on the final location of the DJJ and the cecum, the mesentery may therefore have a narrow attachment at its base. This narrow fan of mesenteric tissue is at risk for rotating around its central axis of the SMA and SMV. Such volvulus may obstruct the SMA and lead to bowel ischemia and even necrosis. In malrotation, the body forms fibrous attachments called Ladd bands , possibly in an attempt to fixate the gut. These usually extend from the cecum to the right upper quadrant and may cross the duodenum causing obstruction. The cecum may be located on either the right or left side of the abdomen and is normally located in 20% of malrotations. Imaging to assess malrotation focuses on the location of the duodenum. UGI documents position of the DJJ; on an UGI the normally located DJJ is at the craniocaudal level of the duodenal bulb lateral to the left spinous pedicles ( Fig. 4.1 ). Malrotation may be present without or with obstruction; obstruction may be caused by volvulus or a Ladd band ( Figs. 4.2–4.5 ).

Chronic or intermittent volvulus may present in older infants and children with recurrent abdominal pain and vomiting, failure to thrive, and malabsorption. Internal hernias may also be associated with malrotation and can be difficult to diagnose; patients have symptoms of obstruction. Intestinal malrotation is also present in patients with omphalocele, gastroschisis, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and heterotaxy syndromes.

Duodenal Atresia, Stenosis, shiftenterand Web

Duodenal stenosis and atresia account for 40% of intestinal atresias. During fetal development the duodenal lumen normally becomes obstructed by rapidly proliferating epithelial cells. If normal luminal recanalization fails, duodenal atresia or stenosis results. Prenatal US examinations can be suggestive, but studies performed before gestational age of 20 weeks may not demonstrate the typical findings of polyhydramnios and a “double bubble.” The classic appearance on a radiograph in a newborn is a double bubble of air with no distal bowel gas ( Fig. 4.6 ). Complete duodenal atresia can even be missed in full-term, breast-fed infants because these children may not present with classic findings. Breast-fed infants often ingest lower volumes than formula-fed infants in the first days of life, and volume of emesis may be small; difficulties with feeds may initially be attributed to difficulties with breast-feeding rather than obstruction.

A small luminal opening present in an obstructing diaphragm across the duodenum causes a duodenal web. While the web may allow the liquid diet of infants to pass, the partially obstructed proximal duodenum dilates. Radiographically this manifests as a double bubble with distal gas ( Fig. 4.7A ) and a “wind sock” appearance on contrast studies ( Fig. 4.7B ). These children often experience feeding difficulties when solid food is introduced to the diet or may have complications after an ingested foreign body.

An annular pancreas develops when there is abnormal fusion of the fetal ventral and dorsal pancreatic buds. If the ventral bud does not properly dorsally rotate during duodenal growth, the pancreas may encircle the duodenum when fusing ( Fig. 4.8 ). Patients may present with obstruction in the newborn period or later. Annular pancreas can be associated with malrotation (a more likely cause of obstruction), tracheoesophageal fistula, anal atresia, and cardiac anomalies, often in the setting of trisomy 21 or Cornelia de Lange syndrome.

A preduodenal location of the portal vein occurs when there is abnormal involution of the embryological vascular structures that give rise to the portal system. Although by itself this abnormality may cause obstruction, the obstruction is usually due to the entities with which it is associated: midgut malrotation, duodenal web, and annular pancreas, often in heterotaxy syndromes. If detected, its presence should be described to avoid injury during surgery.

Distal Obstruction

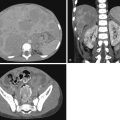

If the initial radiograph demonstrates distal obstruction with multiple dilated loops of bowel ( Fig. 4.9 ), a contrast enema is indicated to determine the cause. If meconium has already been passed, the differential diagnosis includes Hirschsprung disease, jejunal atresia, and ileal or colonic stenosis; if meconium has not been passed, the differential also includes ileal/colonic atresia, meconium ileus, functional immaturity of the colon, and imperforate anus. Imperforate anus with a fistula may allow passage of minimal meconium, and thus imperforate anus can sometimes be missed without careful physical examination.

Jejunal/Ileal/Colonic Atresia/Stenosis

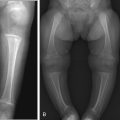

Jejunal and ileal atresias comprise half of all intestinal atresias; colonic atresia is less common, accounting for only 9% of atresias. These atresias may be associated with abnormalities in other organ systems. Unlike duodenal atresia, which is caused by a failure of recanalization of the bowel lumen, distal atresias are thought to result from in utero vascular accidents. Multiple foci of bowel atresia may occur in one patient. Proximal small bowel detritus forms meconium; thus in jejunal atresia the infant may pass meconium, whereas with ileal or colonic atresia meconium will not be passed. Radiographs in jejunal atresia typically show dilatation of the stomach, duodenum, and one or a few loops of additional bowel ( Fig. 4.10 ); there may be a “triple-bubble” appearance. In more distal atresias, multiple dilated loops of bowel are more commonly seen ( Figs. 4.11 and 4.12 ). Regardless, further workup is performed with contrast enema to locate the level of the obstruction. The more distal the atresia location, the more “unused” the colon is, often resulting in a “microcolon” appearance on enema.

Functional Immaturity of the Colon

Meconium plug and small left colon may represent slightly different presentations of the same entity, caused by functional immaturity of the bowel. These infants are occasionally children of mothers with diabetes, or mothers who received magnesium sulfate, and there is delayed passage of meconium. There is no true obstruction, and the symptoms usually resolve without treatment. If a cast of meconium is seen within the descending colon during contrast enema, it is termed meconium plug ( Fig. 4.13 ); if there is no plug but the descending colon is of decreased caliber compared with more proximal colon, it is termed small left colon syndrome . In some cases rectal biopsy is obtained to exclude Hirschsprung disease.

Meconium Ileus

Presenting almost exclusively in infants with cystic fibrosis, meconium ileus is true obstruction of the bowel by dense pellets of meconium. It causes 20% of infantile intestinal obstruction and is the initial presentation in 15% to 20% of patients with cystic fibrosis. Abnormal ion transport caused by the defective Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) chloride channel transporter in this disease yields highly viscous, tenacious meconium that is difficult to pass. This can be seen on radiographs as a bubbly appearance in the bowel loops in the right lower quadrant ( Fig. 4.14 ). Calcifications on initial radiograph suggest meconium peritonitis from intrauterine bowel perforation; meconium spilled in the peritoneal cavity often calcifies and may form a “meconium cyst.” Enema with diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium solution (Gastrografin, Bracco Diagnostics, 1:5 dilution in water) is suggested when this entity is suspected, because this agent may be therapeutic, assisting in breaking up the meconium for easier clearance.

Hirschsprung Disease

Hirschsprung disease causes 15% to 20% of bowel obstructions in newborns, occurring in 1/5000 live births. It may be missed in the newborn period and present later in childhood. The myenteric plexus of the autonomic nervous system normally migrates from proximal to distal along the length of the gut; in Hirschsprung disease, migration does not progress normally all the way to the rectum. The noninnervated bowel is unable to relax and normally propagate peristaltic waves, causing a functional obstruction. This is evaluated on contrast enema by locating a transition zone between the typically normal-caliber bowel distal to the point of obstruction and the dilated bowel proximally. This transition zone usually occurs in the rectosigmoid region, causing a reversal of the normal rectosigmoid ratio. Instead of the rectum being larger than the sigmoid ( Fig. 4.15 ), the obstructed sigmoid dilates and is larger in caliber than the rectum ( Fig. 4.16 ). The bowel at and distal to the transition zone requires surgical excision because functional peristalsis cannot be restored to noninnervated bowel. Because the transition zone can occur anywhere along the course of the gastrointestinal tract up to the esophagus, proximal transition, which is not compatible with life, occasionally occurs. Total colonic Hirschsprung disease can be difficult to detect with contrast enema, because no caliber change may be seen. In these cases the colon may have a “question mark” configuration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree