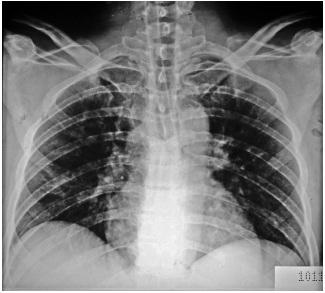

Many patients are treated for respiratory failure and thus a patent airway and adequate oxygenation are critical components of their care. There are many problems that lead to endotracheal intubation. Among these are failure of the patient to have adequate gas exchange, the possibility of airway obstruction, and an attempt to provide airway protection. Any one of these conditions will lead to the placement of an endotracheal tube (ETT). A positive-pressure mechanical ventilator is most often attached to the endotracheal tube. Chest x-rays are indicated after intubation to ensure the proper position of the tube and to check for possible complications (Fig. 4.2). An ETT can be placed by an oral or a nasal route, but the most important consideration is to check the position of the tip of the tube in relation to the carina.20

Figure 4.2 A lateral film of the neck reveals the normal position of a nasaogastric tube posterior to the endotracheal tube.

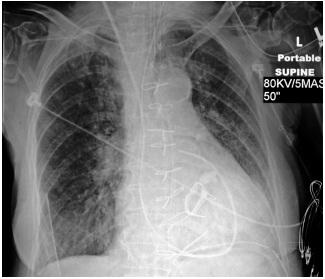

In patients with respiratory failure, a positive-pressure mechanical ventilator is generally used, and this requires placement of an ETT. A portable chest x-ray is obtained to determine whether the endotracheal tube is in proper position (Fig. 4.3). The ideal position for the tube is in the mid-trachea, approximately 4 cm above the carina.20,21

Figure 4.3 A portable x-ray reveals good position of the ETT approximately 4 cm above carina. Note the intra-aorta balloon pump in mid-dorsal aorta.

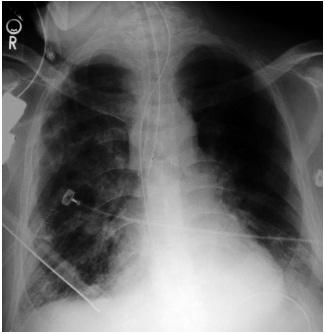

This distance from the carina has been shown to be optimal because it allows a safe margin if the head is maximally flexed, which could drive the ET tube downward, or if the patient extends his head, elevating the tube. Proper placement of the tube will prevent it from either riding too high or slipping down, generally into the right main stem bronchus, resulting in inadequate ventilation of the left lung (Fig. 4.4).22

Figure 4.4 An endotracheal tube in the right main stem bronchus caused by the patient flexing his head, which moves the tube downward.

The carina is identified by tracing the left main stem bronchus back to its junction with the right main stem bronchus.

When the carina can not be visualized on the radiograph, one can estimate its position by identifying the T4–T5 interspace, which generally indicates the location of the carina. Improper placement, if undetected, can cause hyperinflation and possibly pneumothorax of the intubated side. If an endotracheal tube is not advanced far enough, inadvertent extubation can occur or the tube could ride up high enough to put the vocal cords at risk.23 One can visualize the endotracheal tube by visualizing the thin radio opaque line along its length.

The cuff of the endotracheal tube should be inflated sufficiently to occlude the airway but should never exceed the width of the trachea. If one visualizes a bulge in the tracheal wall, this indicates overinflation of the balloon, which can result in damage to the tracheal mucosa, with secondary complications such as ulceration and stricture (Fig. 4.5).24

Figure 4.5 The cuff on the endotracheal tube is overinflated, which may cause ischemia of the tracheal mucosa.

One must be alert to the possible malposition of the endotracheal tube into the pharynx, resulting in aspiration and vocal cord damage.

Esophogeal intubation, another complication, can be recognized by the overdistention of the balloon, lateral displacement of the tube relative to the trachea, and overdistention of the stomach (Fig. 4.6).25

Figure 4.6 Note that the endotracheal tube is not within lumen of the trachea but rather in the esophagus.

A very uncommon complication of intubation is tracheal rupture. This probably is related to the use of a stylet; often, the rush of performing the procedure in an emergency results in rapidly apparent subcutaneous emphysema and occasionally pneumothorax.26

There has been controversy over whether postintubation and daily films to check the position of the endotracheal tube are necessary. Many studies have revealed that significant malposition of the endotracheal tube is identified approximately 30% of the time. Based on current available data, a postintubation chest xray is indicated for nearly all patients undergoing translaryngeal intubation.27

The long-term complications of a patient who is intubated include a high risk of sinusitis, atelectasis, and various types of infections. Intubated patients are also at risk for significant barotrauma. Even aspiration pneumonia can occur in intubated patients because secretions and gastric aspirate can accumulate above the cuff of the endotracheal tube and make their way into the lower respiratory tract when the cuff is periodically deflated.

It is extremely important for one to be vigilant about the extent and progression of variations in lung volumes and infiltrates when one interprets a chest x-ray on a patient who is on a ventilator. Improvement or deterioration may be more apparent than real. Apparent improvement in pulmonary infiltrates and a decrease in the size of the vascular pedical and of the heart are seen with increasing pressures and increasing tidal volumes delivered by the respirator. An apparent worsening of any infiltrate and mediastinal widening may be related to a decrease in respiratory support and may also be seen after extubation.28

When long-term intubation is required, an ETT will eventually be replaced by a tracheostomy tube. This has several advantages over the ETT tube. First, changes in the position of the head will not affect the tip of the tube. The proper position of the tracheostomy tube is one half to one third the distance between the tracheal stoma and the carina, and its width should be approximately two thirds of the tracheal width. The tracheostomy tube should be within the center of the trachea without either of its edges rubbing against the side walls of the trachea. Malposition may lead to abrasion and secondary erosion of the trachea, resulting in either stricture or possible perforation of the trachea. If a cuff is used, it should hug, but not overdistend, the wall of the trachea.29

After performing a tracheostomy, a chest x-ray should be obtained. At that time, one should search for a pneumomediastinum or a pneumothorax. Occasionally, a lateral view is helpful in determining the correct position of the tracheostomy tube.

Central venous catheters are often used in ICU patients to administer medication or intravenous fluids. They are also used to obtain blood for analysis or to measure central venous pressure. Catheters are inserted either in the upper extremity veins (picc lines) proximally, in the subclavian vein, or in the internal jugular vein. The femoral vein is not often used. Triple lumen catheters are used for short-term renal dialysis, and ports are placed in the chest wall of patients requiring repeated doses of chemotherapy or other forms of pharmacotherapy. The superficial and deep veins of the upper arm end up forming the axillary vein, which at the outer border of the 1st rib continues as the subclavian vein. The internal jugular vein joins the subclavian vein to form the brachiocephalic vein.

The left brachiocephalic vein begins behind the sternal end of the left clavicle and runs anterior to the left subclavian and common carotid arteries. It runs retrosternally arches posterially and crosses the midline to join the right braciocephalic vein and form the superior vena cava.

Central venous catheters are most often thin, moderately radioopaque tubes extending centrally from the peripheral sites mentioned. Knowledge of normal venous thoracic anatomy is useful in determining proper catheter placement.

A central venous catheter ideally should be within the superior vena cava, proximal to the right atrium and beyond the most proximal venous valves (Fig. 4.7). These valves are found approximately 1 in. from the end of subclavian and internal jugular veins before they join to form the brachiocephalic vein. Placement of the catheter tip beyond the venous valves is important for an accurate central venous determination. The large caliper of the superior vena cava allows for greater dilution of the many hypertonic or potentially caustic substances administered through the catheter. The ideal position is just above the right atrium and not in the proximal third of the superior vena cava. Central venous catheters located within the proximal third of the superior vena cava are 16 times more likely to thrombus than those in the distal third of the superior vena cava.

Figure 4.7 The central line is in a good position in the superior vena cava just above the right atrium.

The position of the catheter is critical; those that are placed too far distally can enter the right atrium, potentially producing ventricular arrhythmias or even cardiac perforation.30 Another potential complication that can occur, especially when using the subclavian approach, is a pneumothorax.31 A chest x-ray should be obtained immediately after placing a central venous line via this route. There is debate in the literature about whether routine chest radiographs after insertion of central venous catheters are necessary in all patients. Many studies question the value of a chest x-ray’s utility because, in competent hands, the number of complications is quite low. Other studies have shown that as many as one third of central venous catheters are not in the correct position on the initial radiograph.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree