The common pathogens in nosocomial pneumonia are aerobic gram negative organisms and Staphylococcus aureus.82 Gram negative pneumonias have become much more frequent over the past two decades due to an older patient population and more medically diverse, and sicker, patients. The gram negative organisms are predominately Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and occasionally Serratia. These organisms are generally present in the ICU, and oropharyngeal colonization occurs rapidly.

A patient admitted to a medical ICU rapidly becomes infected with gram negative organisms. Oropharyngeal colonization sets the stage for aspiration into the trachea and lower lung fields, leading to the development of pneumonia.83 The majority of gram negative pneumonias in the ICU are due to prior oropharyngeal colonization.84 In some hospitals, Staphylococcus aureus remains a major nosocomial etiologic agent, due to the development of methicillin resistant strains. Unusual agents such as Legionella85 have been responsible for several outbreaks of pneumonia, especially in elderly patients, secondary to contaminated hospital water sources. Immunocompromised patients and patients who have been on steroids or immunosuppressant drugs may develop unusual infections with organisms such as Aspergillus or mucormycosis.86

Diabetes is an additional risk factor, and on occasion we see a diabetic patient with Candida pneumonia.87

The risk of a patient developing a nosocomial infection is 10–25% higher in patients who require intubation and mechanical ventilation than in other patients.88 The endotracheal tube or tracheostomy tube allows the direct access of bacteria to the lower respiratory tract. The mechanical trauma to the tracheal wall may predispose the patient to the development of pneumonia.

Both the pharynx and the stomach are reservoirs for gram negative organisms, which are the precursors of the development of pneumonia in intubated patients. About 25% of patients who are intubated for more than 3–4 days will develop pneumonia.89 Another abnormality to search for on the chest radiograph is an air–fluid level above the lucency of a cuffed endotracheal tube. This represents fluid caught in the pharynx above the balloon; if present, this should be suctioned regularly to prevent aspiration.90

There is often retrograde colonization of the pharynx and the trachea from the stomach. This may also occur secondary to nasogastric tube placement. The tube may interfere with the lower esophageal sphincter, increasing the incidence of reflux and, eventually, tracheal involvement. Feeding the patient via tube in order to meet increased caloric needs also leads to a higher incidence of reflux and the development of pneumonia. In an effort to decrease the incidence of reflux, one may occasionally consider the possibility of feeding the patient via a jejunal tube. Most studies show that the predominant factor in the development of nosocomial pneumonia is aspiration of pharyngeal or gastric fluid in the mechanically ventilated patient.91 We must not forget, however, that approximately 25% of all pneumonias may be due to a primary pneumonia or a pneumonia secondary to a blood-borne infection. Respiratory therapy equipment may also be a potential source of bacterial contamination and subsequent pneumonia, and one must not forget that the hands of the health worker, which pass from patient to patient, are colonized with various types of bacteria and are a potential source of contamination among patients.92

A diagnosis of a nosocomial pneumonia may be reliably straightforward when the clinical picture reveals an intubated patient who has developed fever and leucocytosis while in the ICU. But in the ICU patient, many of whom have many other sources of pulmonary infiltrates, the diagnosis of pneumonia is not so evident. People have attempted to make the diagnosis via invasive methods such as transtracheal or fiberoptic broncoscopy. These techniques have never been shown to improve outcome or survival, and their utility is questionable.

The radiologic evaluation reveals confluent opacities with illdefined borders and, occasionally, loss of the cardiac or diaphragmatic border, the silhouette sign (Fig. 6.2).

Figure 6.2 A portable film reveals a classic silhouette sign. Note the obliteration of the right hemidiaphragm with preservation of the right cardiac border, indicating there is pneumonia in the right lower lobe, although the right middle lobe still aerating well.

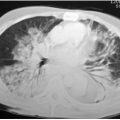

Air bronchograms are often seen and are helpful in establishing the diagnosis (Fig. 6.3).

Figure 6.3 Note the classic air bronchogram with this extensive right upper lobe pneumonia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree